Thirty Years Since Canadian Rowing’s Reign in Spain

July 30, 2022By Jason Beck

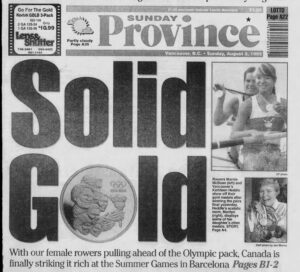

The Monday immediately after the 1992 Olympic rowing regatta happened to be the annual BC Day holiday. Based on the historic performances the previous two days of Canadian rowers either born, raised, or residing in BC, you could make the argument that every day that weekend at Spain’s Lake of Banyoles was BC Day.

previous two days of Canadian rowers either born, raised, or residing in BC, you could make the argument that every day that weekend at Spain’s Lake of Banyoles was BC Day.

There was no rain that week in northeastern Catalonia’s 38-degree heat three decades ago, but there was ‘reign’ of a different kind: without a doubt Canadian rowers reigned in Spain, winning four Olympic rowing gold medals and a bronze that might as well have been golden for the remarkable comeback story that accompanied it. It still stands as the most gold medals Canada has ever won in rowing at an Olympic Games. Each of these five medals won over two electrifying days of finals had direct connections to BC rowers. Given that it is thirty years nearly to the day since this record rowing haul, let’s take a look back at one of the most memorable weeks in BC and Canadian rowing history.

After Canada’s men’s and women’s rowers were completely shut out of the rowing medals at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, strong performances at the 1991 World Rowing Championships in Vienna raised expectations going into Barcelona 1992. At the ’91 worlds, Canada’s women had claimed four of the six gold medals in the women’s heavyweight events taking the eights, coxless four, and coxless pair with Victoria’s Silken Laumann claiming the single sculls. The Canadian men’s eight added a silver. They were looking to maintain and even build on those results. Even some of the leadership at Rowing Canada didn’t think they could possibly duplicate that in Barcelona. Regardless, they never let up in their training and preparation in any way and, if anything, they slammed the hammer down even harder.

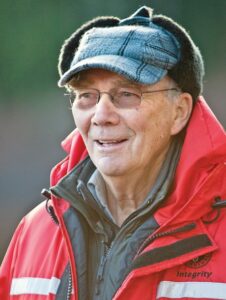

There had been a changing of the guard in Canadian rowing following the dismal 1988 Olympic results in which the men’s eight was the only Canadian crew to advance to the finals, and even then they finished last. The organization cleaned house to start fresh. New national team coaches were appointed afterward: Mike Spracklen on the men’s side, Al Morrow on the women’s.

There had been a changing of the guard in Canadian rowing following the dismal 1988 Olympic results in which the men’s eight was the only Canadian crew to advance to the finals, and even then they finished last. The organization cleaned house to start fresh. New national team coaches were appointed afterward: Mike Spracklen on the men’s side, Al Morrow on the women’s.

Spracklen had coached rowing crews in Britain for well over a decade including some that featured Sir Steven Redgrave, considered one of the greatest rowers in history. Spracklen was hired by Rowing Canada to lead the men’s program in 1989 and based the team’s training headquarters out of Elk Lake in Victoria.

From Ontario, Morrow himself had been a member of the Canadian national rowing team in the early 1970s before coming west and to coach the UBC men’s rowing team beginning in 1976. Two years later he became head coach at the University of Victoria while also coaching at the national training center at Elk Lake. Two years after moving back to London, Ontario, in 1990 he was appointed head coach of the Canadian women’s team. Morrow and Spracklen were on the same page on two fundamental principles going forward.

“Before Seoul [in 1988] we had a lot of good bodies, a lot of good athletes, but they were spread out in five or six boats,” Morrow told the Vancouver Sun’s Archie McDonald in 1992. “Different coaches were fighting to get people into their boats. The system was wrong. When Mike got here, he put the eight best in the eight. We did the same with the women with the exception of Silken Laumann.”

The other fundamental they agreed upon was hard work. Lots of it. They crews would train three times a day almost every day. Nineteen training sessions a week became the standard. Spracklen’s philosophy came to summarize the new program’s direction: ‘Mileage makes champions.’ It was such a grueling schedule that although some time was left to work a day job, most didn’t have the energy. They lived spartan lives getting by on meagre athlete support funding from Sport Canada and wholly devoting themselves to the oar, their teammates, and going faster as a unit.

“Most of the British, for instance, have jobs and train in the morning and the evening. You can still achieve a high level like that. But in the end you are talking about that much,” said Spracklen, holding his hands a foot apart. “Our guys may have given up their jobs for one foot. But then you are talking about difference between success and failure because the silver medal is a loser’s medal.”

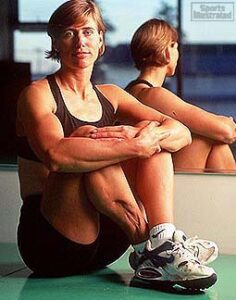

Many of the crew members literally put their lives on hold and uprooted themselves from different parts of the country moving to Victoria to train full-time like Silken and her then-boyfriend John Wallace, a member of the men’s eight. After the Olympics, a few would remain and make BC their homes from then on.

The crews trained hard on Elk Lake through the winter of 1992, Silken choosing to train with the men under Spracklen, while the rest of the women continued working under Morrow.

“Silken was always a big presence because she had done well and was a bit older than us,” said Kathleen Heddle in a 2006 interview with ProMotion Plus. “Sort of a first phase of success in this new era of Canadian rowing in the late 1980s. She was the one to get that going. Always a big figure and an inspiration for us.”

“Silken was always a big presence because she had done well and was a bit older than us,” said Kathleen Heddle in a 2006 interview with ProMotion Plus. “Sort of a first phase of success in this new era of Canadian rowing in the late 1980s. She was the one to get that going. Always a big figure and an inspiration for us.”

In the spring both the Canadian women and men went to Europe for a series of pre-Olympic regattas. Everything was going according to plan until warm-ups at a World Cup regatta in May in Essen, Germany when disaster struck.

Silken was out on the water in the chaotic and poorly organized warm-up area amidst dozens of other boats going every which way, everyone trying to focus on pulling some hard strokes to limber up, while also keeping their heads on a swivel for other boats nearby. She described what happened next in her 2014 book Unsinkable:

“I had taken twelve strokes, aggressively and fluidly, when I heard a whirr like a strong wind blowing across my riggers, followed by a slight delay as my mind grasped its meaning. The German men’s pair came crashing into the side of my Stampfli [shell] with a crushing sound, fierce and screeching and devastatingly violent… Colin van Ettingshausen’s face was white and his eyes wide as he stared at my right leg. I hadn’t thought to check myself for injury, but now I stared, too: it was torn open… Flesh, bone, blood, all mangled together—it seemed unrecognizable as my leg.”

Silken was rushed to the hospital where she underwent emergency surgery to save her leg. There was significant risk of infection as splinters from Silken’s shattered shell had been driven into her calf muscle. The surgery went well, and doctors were optimistic that Silken would be able to walk again albeit with a limp for the rest of her life. Her Canadian teammates were devastated for her.

“That was a huge shock for the team,” said Heddle in 2006. “It was a pretty big blow for everyone.”

The Olympics, just 10 weeks away in late July, initially weren’t even a consideration—to everyone except Silken. Everyday as she lay in her hospital bed recovering from the latest procedure on her leg, she began visualizing that it was healing and strong.

“One crazy thing became increasingly clear: I wasn’t wanting to heal my leg just to be healthy again,” she said. “I intended to row and win a medal in Barcelona, despite my lower leg being a huge open wound, with dead tissue still to be removed to decrease the risk of infection, and with a skin graft yet to come.”

Just three days after the accident, Silken tied two rubber Thera-Bands to the end of her bed and began pulling on them as if they were oars. She flew home to Victoria where further procedures and physio continued at Royal Jubilee Hospital. She astounded doctors and everyone who came to visit her with her laser focus and determination.

Twenty-three days after her accident, getting around in a wheelchair and her right leg in a prosthesis, she was taken to the dock at Elk Lake to try rowing again. Barely able to stand due to the pain but sitting in her scull on the water Silken was back in her element and she zipped joyfully all over the lake to everyone’s amazement. A timed 2000m row a few days later 75 seconds slower than normal revealed how much conditioning she had lost in the past few weeks though. Regardless, she continued to put the work in and spurred on by constant encouragement from her teammates by phone and mail, she improved regaining fitness and strength. By the end of June, she had rejoined Spracklen and the men’s national team training in France and was rattling off 300km training weeks courageously trying to claw back all the fitness and strength she’d lost since the crash.

At that point, Silken’s accident and recovery had been detailed in the media from coast-to-coast, a running national story. The question became not whether the defending world single sculls champion could compete at the Olympics, but how she would do.

In mid-July the Canadian men’s and women’s rowing teams settled into their Olympic accommodations, a satellite athlete’s village just for the rowers at Lake of Banyoles, a 125km drive northeast of Barcelona. Being a 90-minute drive from the center of the Olympic circus, the rowers may have thought they could sharpen their final preparations mostly out of the media spotlight. But because of Silken’s situation and the heightened expectations for all the Canadian crews in general, there still was plenty of media to contend with daily.

In mid-July the Canadian men’s and women’s rowing teams settled into their Olympic accommodations, a satellite athlete’s village just for the rowers at Lake of Banyoles, a 125km drive northeast of Barcelona. Being a 90-minute drive from the center of the Olympic circus, the rowers may have thought they could sharpen their final preparations mostly out of the media spotlight. But because of Silken’s situation and the heightened expectations for all the Canadian crews in general, there still was plenty of media to contend with daily.

Through training, the opening of the Games, then heats and semifinals, everything built up to two days of finals at the Olympic regatta held on August 1st and 2nd. No one could have predicted what was in store for Canada’s sisters and brothers of the oar.

The Canadian medal parade started with the women’s straight four. Three of the four team members had strong BC ties. Kirsten Barnes grew up in

Vancouver and rowed at the University of Victoria, where she was named the school’s Female Athlete of the Year three consecutive years. North Vancouver’s Jessica Monroe got her start in the water as a member of the False Creek dragon boat team, but switched to rowing and made the national team in 1989 following in the footsteps of her older sister Joanell and brother-in-law Tim Storm who both rowed at the 1984 Olympics. From Nanaimo, Brenda Taylor, renowned for her aggression and endurance, had been a member of the national team since 1984. Rounding out the four was the veteran Kay Worthington from Toronto, a last-minute replacement for Jennifer Doey Walinga from Lambeth, Ontario, who was pulled from both the four and eight crews due to back spasms just a day before the Games opened. It was heartbreaking for Doey, but also threw the expectations for the four, the 1991 world champions, into some doubt.

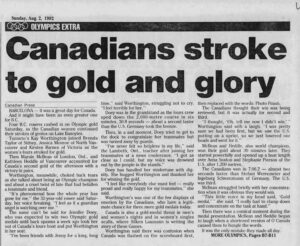

However the Canadian four cast aside any fears with a strong performance in their heat finishing well in front of their American rivals and winning in 6min 44.11sec, advancing straight to the finals. The Americans made the final too through the repechage and in the final on August 1st came the closest to dethroning the Canadian four, but Barnes, Taylor, Monroe, and Worthington stroked clear to Canada’s first-ever Olympic gold medal won in women’s rowing finishing in 6min 30.85sec, a full second in front of the Americans.

Surprisingly, the last-minute crew change didn’t throw off the Canadian women in any way.

Surprisingly, the last-minute crew change didn’t throw off the Canadian women in any way.

“We have been rowing in different combinations since January, so it’s not that much of a difference,” said Taylor to the Province’s Kent Gilchrist. “It helps a lot that we all get along and respect each other.”

Doey was watching from the stands as her crew sliced across the finish line in first. She tried to get down to the dock to celebrate with her teammates but sadly her pleas were drowned out by the roaring crowd and she was turned away by security guards. It was the only sad moment for the Canadians as half an hour later there was more maple leaf magic on Lake of Banyoles.

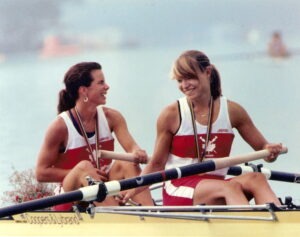

In the women’s straight pair, Kathleen Heddle and Marnie McBean were often described as the ‘odd couple’ for their vastly different personalities. McBean, born in Vancouver and raised in Toronto, was full of bubbling energy, outgoing and outspoken, fiery at times. Heddle, born in Trail and who learned to row while attending UBC, was much more reserved, shy even, cloaking enormous inner physical and mental strength. Most considered Heddle the strongest rower in any crew she appeared in.

“Kathleen is Vancouver,” said coach Morrow to Maclean’s magazine in 1992. “She’s West Coast laid back and Marnie is hustle-bustle Toronto. The beauty of it is that as a pair, they offer each other those strengths.”

“We did struggle a lot because we are very different people,” said Kathleen in 2006. “We have a different approach to life and to sport and how to prepare for an event. We had a lot of conflict over the years, but I think in the end we were able to work through those things and understand each other. In the end, we were able to balance each other out.”

Both had discovered rowing relatively late—Kathleen in her third year of university when a coach picked her out of a line-up on registration day because her height, Marnie through a learn-to-row course at Toronto’s Argonaut Rowing Club at age 16. After earning spots on the national team, they were first paired together in 1991. Each went on their own at different times to Morrow begging for a new partner. Morrow convinced them to see the plan through, but no one could have predicted the success that was to come.

They may have been opposites in so many ways, but they also developed into one of the greatest pairings in any sport in Canadian history. After winning the pairs world championship in 1991, the Barcelona Olympics were next. They won their first heat comfortably and then showed another gear dominating their semifinal and winning easily 7min 18sec, over 23 seconds faster than their heat.

In the final on August 1st, just half an hour after the Canadian women’s four had struck gold, it was McBean and Heddle going for the gold medal. The German pair of Ingeburg Schwerzmann and Stefani Werremeier pushed them harder than anyone thus far, but the result was never really in doubt for the Canadian pair as they opened up a full boat-length lead by 1200m and carried it home. Kathleen and Marnie won in 7min 6.22sec with the German pair 1.7 seconds behind. With searing heat and strong competition, the race had been a physically painful one, but as Kathleen said later: “We trained for the pain.”

Standing up on the podium later, Kathleen and Marnie were proudly singing along to O Canada, when they started laughing, realizing the anthem had been strangely shortened due to television time restrictions and they had mixed up the words.

“When the anthem played, nobody told us that they would be shortened down with a verse missing,” chuckled Marnie to the CBC in 2020. “I mean, why wouldn’t you think to tell Canadians that their anthem is going to sound a little funky?! Because no one expected to hear it.”

It proved the only mistake Kathleen and Marnie made all day but didn’t take away from their golden moment one bit. And the best part? There was more to come on Day Two of the finals the next day.

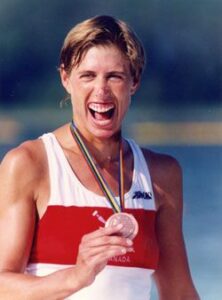

It started off with the women’s single sculls, where all eyes were on Silken. Let’s be honest, it was an absolute miracle that she had willed herself to even be competing at the Olympics after her horrific accident in May. And then having somehow made it to Lake of Banyoles, there was then the inevitable crushing media attention that she was now shouldering each and every moment. She began holding her own daily press conferences to ease the pressure a bit. And it wasn’t like she could just hide.

“I was quite a spectacle…leaning on my cane as I made my way through the boat area, my right leg bandaged,” she recalled in Unsinkable.

Her first competitive test since the accident came in the opening heat of the single sculls. Still shaking off the rust and adapting to her still healing leg, Silken finished in second six seconds behind the American sculler Anne Marden, a silver medalist at the 1988 Olympics. Silken called the race “solid, but my pacing was off.”

It wasn’t her best, but it did provide hope that she could muster more. Every waking moment until the next race she spent in physiotherapy. Then came the semifinal, which she won in 7min 30.48sec—16 seconds faster than the heat—which qualified her for the final. The result was not only more promising, but it was also startling. Humans aren’t supposed to do these sorts of things 10 weeks after nearly losing a leg. But Silken was causing everyone to re-think what was possible.

“I had a spectacular race, rowing sharp and strong,” she recalled. “I shocked myself, as well as the rest of the field, when I came in first. …it was also critical in lifting my confidence for the final, two days away.”

It would have been hailed as an achievement just to be back in the boat by this time after her accident. It would have been remarkable to even make the final. But having accomplished those, now this was astounding that she was in serious medal contention. Everyone in Canada and many around the world tuning in on August 2nd seemed to be asking the same question: ‘Could Silken actually win a medal too?’

As she positioned her shell at the start line for the final, there were so many photographers focused in on her that her dock was almost sinking under the weight of them all.

Finally, the starting gun blasted and the six best scullers in the world were off chasing a finish line 2000m away. Silken burst from the gates fast and stroking smoothly. For the first 500m, it felt like any other race, but then she noticed the toll the accident, the resulting injury, and everything else had taken on her.

“My strokes felt less lively and more laboured, and I was struggling for oxygen—a feeling unfamiliar to me, since aerobic fitness was usually my strong suit.”

She settled in for the fight of her life and was holding on in third place. By the halfway mark, Elisabeta Lipă of Romania had built a commanding two-length lead with Annelies Bredael of Belgium following in second. Silken was in third, 3.74sec behind Lipă and 0.33sec behind Bredael.

With 500m to go, Silken was still in third but clearly struggling. The American Anne Marden, who had beaten Silken in the opening heat, was now even with her and looking strong. Shortly after, Marden pulled ahead of Silken who dropped to fourth. Most everyone watching likely conceded it had been a gallant, extraordinary effort by the Canadian, but asking just a little too much at this level of competition. Somehow that thought never entered Silken’s mind.

With 500m to go, Silken was still in third but clearly struggling. The American Anne Marden, who had beaten Silken in the opening heat, was now even with her and looking strong. Shortly after, Marden pulled ahead of Silken who dropped to fourth. Most everyone watching likely conceded it had been a gallant, extraordinary effort by the Canadian, but asking just a little too much at this level of competition. Somehow that thought never entered Silken’s mind.

“[Marden] pulled out and I think at that point I thought that maybe I’d lost contact with her and I looked and realized that we were still very close,” she said to the Greater Victoria Sports Hall of Fame upon her induction in 2004. “I just suddenly thought, ‘I’m not coming in fourth!’ Fourth is the worst position, to just miss a medal.”

Something truly remarkable then took place.

“I could hear the crowd roar—crazy amounts of noise for a rowing race, amplified by the enthusiastic Canadians filling the floating grandstands,” Silken recalled. “I had nothing left. I was seizing up. My head was foggy, but I was not going to come in fourth. At that moment, some force took hold of my oars. I lifted my rate—one, two, three strokes more a minute. My body had been trained for this sprint, and now a force of power, love, and grace drove my boat ahead of Anne’s and over the finish line. I was so confused with exhaustion and my body’s screaming from lactic acid, I didn’t know where I’d finished. When I read the scoreboard…I breathed a sigh of relief. Not elation, not a triumphant fist-in-the-air punch, just relief and exhaustion, and an amazing, encompassing feeling of completion. I had done it.”

recalled. “I had nothing left. I was seizing up. My head was foggy, but I was not going to come in fourth. At that moment, some force took hold of my oars. I lifted my rate—one, two, three strokes more a minute. My body had been trained for this sprint, and now a force of power, love, and grace drove my boat ahead of Anne’s and over the finish line. I was so confused with exhaustion and my body’s screaming from lactic acid, I didn’t know where I’d finished. When I read the scoreboard…I breathed a sigh of relief. Not elation, not a triumphant fist-in-the-air punch, just relief and exhaustion, and an amazing, encompassing feeling of completion. I had done it.”

Somehow the still-injured Silken Laumann had willed herself back into the bronze medal position finishing in 7min 28.85sec behind Lipă and Bredael. It stands as one of the greatest comebacks in the history of the Olympics. Certainly the greatest in Canadian history.

“You saw Silken drop into fourth place and show tremendous determination to come back,” coach Spracklen told Michael Farber of the Montreal Gazette. “That’s an extremely hard thing to do. She wanted to win very badly to have gone through that situation. In the last 500 [meters] to lose your place and regain it, that just doesn’t happen. You’ve got to be someone very special to do that.”

Canadian teammate Kay Worthington, Silken’s old doubles partner, went even further calling her performance “inhuman.”

Silken’s bronze medal became front page news in every city across Canada and in headlines around the world. She was suddenly a household name from coast-to-coast and largely remains so today. Although there were many gold and silver medalists to choose from in Barcelona to carry the Canadian flag at the Games Closing Ceremony, the honour of having Silken do it seemed the only appropriate choice.

If the Olympic regatta had ended right here, most Canadians would have been more than satisfied, but as it turned out, there was more—so much more. And if anything, Silken’s comeback overshadowed gold medal performances that in any other Olympics would have been heralded much more of the spotlight.

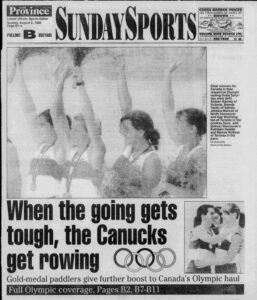

Just minutes after Silken’s signature race, up next was the women’s eight final.

Having won the 1991 world championship—the first-ever world title for Canadian women in rowing—Canada’s women’s eight went into the Barcelona Olympics as the gold medal favourite, but also with something to prove.

Having won the 1991 world championship—the first-ever world title for Canadian women in rowing—Canada’s women’s eight went into the Barcelona Olympics as the gold medal favourite, but also with something to prove.

“We had to prove it wasn’t a fluke,” said Kirsten Barnes in Wendy Long’s 1995 book Celebrating Excellence. “Going into the Olympics we’d had a whole year with peoples’ eyes on us.”

The crew was a powerhouse consisting of Kathleen Heddle and Marnie McBean from the gold-medal-winning straight pair, Barnes, Brenda Taylor, Jessica Monroe, and Kay Worthington from the gold-medal four, as well as Edmonton’s Megan Delehanty (whose club was Burnaby Lake and she attended UBC) and Guelph, Ontario’s Shannon Crawford. The great Lesley Thompson from Toronto, who would ultimately represent Canada at a record eight Olympics and win five medals, was the cox.

In the opening heat, Canada’s women calmly and confidently took care of business winning easily in 6min 11.44sec and advancing straight to the final.

There the Canadian women were even more dominant proving they had more than earned the title of the world’s best rowing crew. The Canadians led from start to finish, winning in 6min 2.62sec—over a full boat length and almost four seconds ahead of the second-place Romanians. It marked Canada’s first-ever Olympic gold medal won in women’s eight rowing.

“That last year especially, it just felt right,” said Barnes to CTV. “Everything really came together. Everyone was working so hard together and all had the same goal. Everyone, we all knew that if we really dug down and worked hard, thought enough about it, it was going to happen.”

“We’re a machine!” exclaimed McBean after to Doug Smith of the Canadian Press.

After the medal ceremony there was a touching moment that showed how tight this crew truly was. Like in the four, Worthington was a last-minute sub in the eight for the injured Jennifer Doey Walinga. Every member of this crew knew that the gold medals won by the four and eight had been earned during countless cold rainy training sessions back on Elk Lake in Victoria. Doey had put in the work just as everyone else had and helped get them to the top of two podiums. As such, Brenda Taylor gave up one of her two gold medals won at these Olympics and gave it to Doey as recognition for her contribution to the teams.

Said Taylor after in Celebrating Excellence: “Our coach Al would always tell us: ‘You win a race by your preparation, your training, your mental focus, your level of fitness. All of those things come together.’ Jennifer did all those things. She was part of that four. You don’t win a race just on the day, you win it through the preparation and Jennifer was part of getting us there.”

It would be 29 years before Canadian women returned to the gold medal position in women’s eights at the Olympics, when Canada won at the Covid-delayed Tokyo Games. That crew dedicated their win to the 1992 crew who was so dominant and groundbreaking.

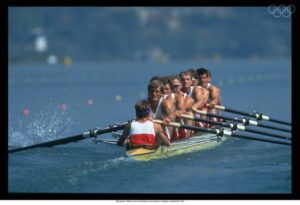

And then there was just one last race left at Lake of Banyoles: the men’s eight final.

And then there was just one last race left at Lake of Banyoles: the men’s eight final.

The Canadian men had taken silver at the 1991 world championships and were certainly a medal contender but were often overshadowed by Canada’s remarkable women. The crew consisted of three crew members developed fully in BC: Victoria’s Derek Porter and Darren Barber, and Fernie-raised Michael Rascher. But there were other BC connections among Spracklen’s crew. Andy Crosby was born in Bella Coola and attended UVic. Rob Marland and his wife made Victoria their home. Mike Forgeron was now living in West Vancouver. Bruce Robertson, John Wallace, and cox Terry Paul all rowed out of the Victoria City Rowing Club.

Wallace had long held the stroke seat in the crew, but just a few weeks before the Olympics, sensing the team needed shake-up, Spracklen surprisingly made the risky move of shifting Porter to stroke and Wallace to bow.

The Olympic regatta started well enough for the men’s eight as they won their quarterfinal heat easily. But in the semifinal they started slowly and allowed Romania to build a lead on them, which they never were able to make up. Romania finished over two seconds in front. The result still qualified the Canadians for the final, but now they too had something to prove.

Canada had already won four rowing medals at these Olympics—would a fifth be asking too much? Canadians tuning into the CTV broadcast found Gerry Dobson doing play-by-play and race analysis by Roger Jackson (1964 Olympic gold medalist in pairs rowing with Vancouver’s George Hungerford, a 1966 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee). They were unexpectedly joined in the broadcast booth by Silken Laumann, fresh off her dramatic bronze medal win and with more than a vested interest in this race as she and men’s eight crew member Wallace were in a long-term relationship at that time.

The final got off to a tight start with very little separating any of the six crews through 500m. The Canadians were laying it all out there from the beginning still stroking at a very high rate of 42 strokes per minute through the first quarter. That pace edged them into the lead in Lane 5 just ahead of Romania in Lane 3. By 1000m, Canada was 10 feet in front with a 0.40sec lead over Romania reversing what had taken place in their disappointing semifinal. The defending world champion German crew sat in third.

By 1500m, Canada’s lead had grown to half a boat length ahead of Romania and Germany, who had separated from the rest of the field behind. But the furious pace began to take its toll on the Canadians as the Romanians and Germans fashioned bursts of their own and began chipping away at Canada’s lead. The Canadians, their faces gripped in tortuous masks of pain, were madly trying to hold on. Dobson captured the drama of the final few meters on the live broadcast:

By 1500m, Canada’s lead had grown to half a boat length ahead of Romania and Germany, who had separated from the rest of the field behind. But the furious pace began to take its toll on the Canadians as the Romanians and Germans fashioned bursts of their own and began chipping away at Canada’s lead. The Canadians, their faces gripped in tortuous masks of pain, were madly trying to hold on. Dobson captured the drama of the final few meters on the live broadcast:

“The Canadian men’s eights looking to make it four gold medals for Canada in the Olympic rowing regatta! They’re looking strong!…The last 50m, the Canadian eights…Romania now with a final push! Romania coming strong! Go Canada! Can they hang on?! They are there, they have just a few meters…YES!!! [collective yell from Gerry, Silken, and Roger] GOLD MEDAL FOR CANADA!”

Terry Paul dove into Porter’s arms after the exhausted Canadians sliced the finish line in a time of 5min 29.63sec just 14 hundredths of a second in front of Romania, the winning margin the length of an oar blade, less than two feet.

“We just hammered it home,” said Forgeron after.

“You give it all you have from start to finish. At the end we had nothing left,” said Porter.

“It’s probably the most emotional I have ever been in a race,” said Spracklen. “I had to pace. I don’t I have ever done that. I actually didn’t see them cross the line—it was a blur. It took me a while afterward to come down to earth.”

With four gold medals and a bronze that might as well have been gold for the comeback it represented, returning home after perhaps the greatest team performance in Canadian Olympic history, the rowers were the toast of Canada.

“I’d won world championships and everything before that, but no one knew about it,” McBean told the CBC in 2008. “This time when I got home, everyone knew. This was different—this was the Olympics. In hindsight, I was really naïve about how big it was.”

It would get even bigger for some from these crews too, including McBean and partner Heddle. They returned four years later to the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta to capture a third gold medal in double sculls and helped the Canadian quadruple sculls crew to a bronze. At that time, the pair stood as the most decorated Canadian Olympians in history. Silken Laumann and Derek Porter also returned, both winning silver medals in single sculls.

Two years after the Barcelona Olympics, based on the residency criteria of the time the BC Sports Hall of Fame inducted seven BC members of the 1992 crews: Kirsten Barnes, Kathleen Heddle, Jessica Munroe, Brenda Taylor, Darren Barber, Derek Porter, and Michael Rascher. If today’s more open residency qualifications had been in place then, it’s quite likely the entire men’s and women’s crews described here would have been inducted as a group based on their collective BC connections. Many members of those crews based at Elk Lake have lived in BC ever since.

Two years after the Barcelona Olympics, based on the residency criteria of the time the BC Sports Hall of Fame inducted seven BC members of the 1992 crews: Kirsten Barnes, Kathleen Heddle, Jessica Munroe, Brenda Taylor, Darren Barber, Derek Porter, and Michael Rascher. If today’s more open residency qualifications had been in place then, it’s quite likely the entire men’s and women’s crews described here would have been inducted as a group based on their collective BC connections. Many members of those crews based at Elk Lake have lived in BC ever since.

Others were also later inducted individually into the BC Sports Hall of Fame: Porter in 1996, Heddle in 2003, and Laumann in 2004.

In 2017, the 1992 crews gathered for a 25-year reunion that coincided with their induction into the Canadian Rowing Hall of Fame. It was a timely and meaningful gathering, appreciated later even more by those who attended after the sudden passing of Kathleen Heddle in early 2021.

Canadian rowing’s ‘Reign in Spain’ all those years ago had truly been a watershed moment for the sport. Maybe no one said it better than Silken: “For Canadian rowers, Barcelona 1992 was a landslide. We had accomplished everything anyone had dared expect—and more.”