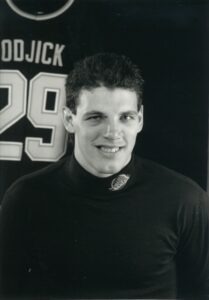

Gino Odjick: Inspirational Fighter – 2021 Inductee Spotlight

June 7, 2022By Jason Beck

“GINO! GINO! GINO!”

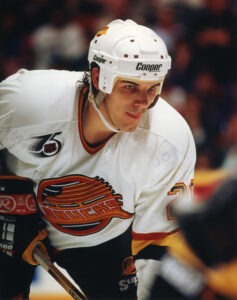

Few athletes are ever lucky enough to experience one instance of a packed arena chanting their name in unison. Rarer still are those whose names are chanted for long periods over the course of their career. But maybe no athlete in the history of BC sport has ever had their name chanted so fervently and for so long as Gino Odjick, one of the most beloved and toughest Vancouver Canucks in team history.

Twenty years after retiring from NHL play, if Gino makes an appearance during a Canucks game at Rogers Arena, you can guarantee 18,000+ will still stand, applaud, and, of course, chant.

“GINO! GINO! GINO!”

For much of the 1990s, odds are if you attended a Canucks home game at either the Pacific Coliseum or GM Place (now Rogers Arena), this chant rang out amongst the arena rafters at some point in the night. Sometimes it was the fans demanding coach Pat Quinn send Gino over the boards to seek retribution for some on-ice offense committed against the home side. More often it came in response to something Gino had done to electrify the crowd: a crunching hit, a nice goal followed by an exuberant celebration, or the most anticipated: Gino dropping the gloves and taking on—and usually taking down—another of the NHL’s heavyweight enforcers.

“GINO! GINO! GINO!”

“GINO! GINO! GINO!”

For over thirty years now, it’s become such an accepted Canuck ritual that we might take for granted how unique and truly special this is.

“I’ve got a great connection with the fans,” said Gino in a recent Zoom interview from his home in Vancouver. “It’s amazing that they still remember. It’s just awesome, that’s for sure.”

“The fans just had such a love for him, could identify with him,” agreed long-time teammate and Canucks captain Trevor Linden, a 2011 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “I think fans are always connected to personalities. They could just see the personality in Gino. It came through on the ice. It came through in his interviews. It came through in the way he celebrated when he scored. Gino’s personality was so on the surface and that’s what people loved about him.”

No one willingly put their body and well-being on the line more often for their teammates, for the team’s betterment, and for the fans than Gino and perhaps the ongoing respect and adulation from Vancouver fans is an acknowledgement of this.

Gino was born in 1970 in Maniwaki, Quebec. His family was of Algonquin heritage and he grew up on the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation reserve about 140km north of Ottawa, the fourth child and only son of Joseph and Giselle Odjick.

It can get very cold in that part of Quebec in the winters, down to -30 degrees Celsius or more. Fittingly, Gino’s earliest memory is of the ice, but it’s not what you’d expect.

“I remember my dad took me figure skating because I was too young to skate with the older kids,” he recalled. “I remember skating with a chair. That’s the first thing I remember. It was figure skating first.”

At age five Gino began playing shinny on the Kitigan Zibi reserve’s outdoor rink. He joined his first organized team at age 11 and played on local youth teams coached by his dad Joseph, who had survived his time in residential school to play junior hockey in Ottawa. Later in the NHL Gino would wear his familiar number 29 jersey because this was the registration number given to his father when he was at the Spanish, Ontario residential school.

“He really loved the game,” said Gino. “He was passionate about it and he really did everything he could to give me a chance to succeed at hockey.”

“He really loved the game,” said Gino. “He was passionate about it and he really did everything he could to give me a chance to succeed at hockey.”

Gino’s dad coached him all the way through midget hockey.

“We travelled and played other First Nations communities,” he said. “We played tournaments all over the place. We really had a good time. We bonded. I had the same teammates from novice all the way through midget. We’re still friends today. We see each other and we have great memories.”

Like everyone he knew growing up, he played hockey in the wintertime and softball in the summer.

“We were basically a two-sport town on the reservation,” he said. “Everybody that was athletic played those two sports.”

But hockey was his undisputed love.

“I was a rink rat,” he chuckled. “I was always at the Maniwaki rink watching. They used to have novice all the way through midgets on Saturdays and I used to stay at the rink and watch. The junior B team, I watched those guys too. I was always trying to learn new plays and just loved hockey. It was a passion for me.”

Years later in 2014, long after his NHL career and he had become an inspiration for a generation of Indigenous youth in Maniwaki and beyond, that same arena would be named in his honour, Le Centre Gino-Odjick.

When Gino was young he followed the Montreal Canadiens and looked up to the great Guy Lafleur, but it was Stan Jonathan, a bruising Boston Bruins left-winger of Tuscarora Iroquois heritage, who he looked up to most.

“That’s who I wanted to be because he was First Nations and he was a tough guy,” Gino said. “Every time I played street hockey I was always Stan Jonathan, play fighting with my friends. He was an idol of mine.”

At age 13 Gino’s Maniwaki team played in the famed Quebec International Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament. His aggressive, physical play with the Hawkesbury Hawks in the Tier 2 Central Canada Hockey League later earned him a spot on the Laval Titan of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. He had mostly played defense to that point, but Laval coach Paulin Bordeleau, a former Canucks center during the mid-1970s, decided to move him up to the wing to protect Donald Audette and Denis Chalifoux, highly skilled scorers who were small and getting pushed around too easily.

At age 13 Gino’s Maniwaki team played in the famed Quebec International Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament. His aggressive, physical play with the Hawkesbury Hawks in the Tier 2 Central Canada Hockey League later earned him a spot on the Laval Titan of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. He had mostly played defense to that point, but Laval coach Paulin Bordeleau, a former Canucks center during the mid-1970s, decided to move him up to the wing to protect Donald Audette and Denis Chalifoux, highly skilled scorers who were small and getting pushed around too easily.

“Paulin said, ‘You’re going to get more ice time and you’ll get more points playing with those guys.’ He was right on both instances,” said Gino.

Battling homesickness, Gino established himself as a fearsome physical force on the ice, creating space for his teammates and chipping in with the odd goal offensively. In the 1988-89 season, he finished with 24 points and 278 penalty minutes in 50 games and the following year increased that to 38 points and 280 penalty minutes in 51 games. He became a fan favourite known by nicknames like the ‘Algonquin Assassin’ and the ‘Maniwaki Mauler.’

Gino helped Laval qualify for two consecutive Memorial Cups where they finished fourth in 1989 and third in 1990. It was at one of these tournaments that Canucks scout and former player Ron Delorme first saw Gino play. Delorme, of Métis heritage, took Gino under his wing giving him pointers and encouraging him as he chased his NHL dream. Delorme’s words carried weight with Gino, who remembered watching Delorme play on TV with the Canucks in the 1982 playoffs, particularly his momentum-shifting fight with Chicago’s Grant Mulvey. It was Delorme who pushed the Canucks to draft the 19-year-old.

“Ronny got to know him before we took him,” said Canucks general manager and coach Pat Quinn, a 2013 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “He told us he was a good kid. The two of them have a bond. I think Ronny helped Gino understand a lot of things.”

“As soon as I learned of my induction, I thought of Ron Delorme right away,” Gino told Jay Janower of Global BC recently.

Gino’s first visit to BC was actually for the 1990 NHL Draft, which was held in Vancouver in BC Place Stadium. After the Canucks selected Petr Nedved second overall, with the 86th pick in the fifth round the Canucks took Gino. When the fact was pointed out to Gino that the stadium in which he was drafted is also the same stadium where he’ll be honoured in the BC Sports Hall of Fame, he smiled wide and exclaimed, “Amazing.”

Gino started the 1990-91 season with the Canucks’ farm team the Milwaukee Admirals, scoring seven goals, totaling 10 points, and racking up 102 penalty minutes in just 17 games. And then, completely out of the blue, the big league came calling.

“We’d just played Muskegon when I got the call and I had to leave the next morning around 6am,” he recounted to Indian Life Magazine in 1994. “Phil Wittliff [Milwaukee GM] came to pick me up at my apartment to take me to the airport and I asked him if he knew how long I was going up for. He looked at me and said, ‘Tell you what, kid, Babe Ruth got called up for one game and never made it back to the minors, so it’s not up to me how long you stay there, it’s up to you.’”

“We’d just played Muskegon when I got the call and I had to leave the next morning around 6am,” he recounted to Indian Life Magazine in 1994. “Phil Wittliff [Milwaukee GM] came to pick me up at my apartment to take me to the airport and I asked him if he knew how long I was going up for. He looked at me and said, ‘Tell you what, kid, Babe Ruth got called up for one game and never made it back to the minors, so it’s not up to me how long you stay there, it’s up to you.’”

Gino clearly took that advice to heart and never stopped working his entire career to be an everyday NHL player. Even today, he ranks that unexpected call-up as the biggest surprise of his career.

“I was just a fifth-round draft choice,” he marveled. “No one expects you to play in the NHL your first year. Twenty games into the season I’m called up and stayed in the NHL for 12 years. That was quite the ride.”

What Gino didn’t know was the Canucks under Quinn were a team in transition with good young players like Linden, Greg Adams, and goaltender Kirk McLean, but getting pushed around more than Quinn would like. When Canucks tough guys Jim Agnew and Ronnie Stern came down with injuries, he thought they should give this hulking 6’3” 220-lb winger running roughshod over everyone in the minors a shot. Gino recounted an early conversation with Quinn on Global BC recently:

“Pat Quinn, as soon as I got here, said, ‘I don’t want a goon, I want somebody who can play. I don’t want you just coming off the bench to fight, you have to contribute. You have to be part of the leadership group. I’m going to give you an opportunity every night to do something special.’ And true to his word, that’s what he did, and I grew as a player from the first day that I walked in as a 20-year-old and when I left as a 32-year-old I was still getting better as a player, so I really appreciate what Pat did for me and I always think of him all the time.”

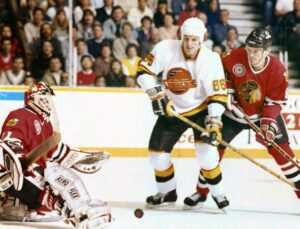

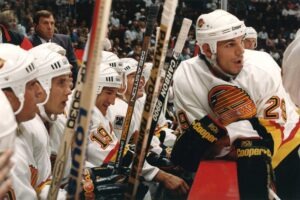

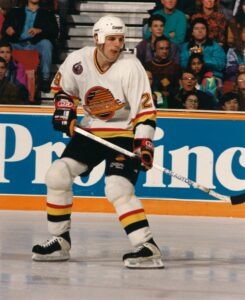

Wearing jersey number 66, Gino made his NHL debut with the Canucks on November 21, 1990 in a game against the Chicago Blackhawks at the Pacific Coliseum. Early in the third period with the Canucks leading 4-0, the bigger Blackhawks began taking some liberties trying to get back into the game. For the first of countless times over the next few years, Gino went out on the ice to put an end to that.

“I got into a fight with Dave Manson,” he recalled of that first game. “We didn’t really get going the way I liked, but towards the end of the game I got into another fight against Stu Grimson, who was one of the toughest guys not named Bob Probert at that time. I did really well in that fight and the fans just went crazy. They started calling my name.”

“I got into a fight with Dave Manson,” he recalled of that first game. “We didn’t really get going the way I liked, but towards the end of the game I got into another fight against Stu Grimson, who was one of the toughest guys not named Bob Probert at that time. I did really well in that fight and the fans just went crazy. They started calling my name.”

“GINO! GINO! GINO!”

Vancouver held on to win 4-1 and a Canucks legend was born right there. For the next eight years there were few Canuck players more widely admired and loved.

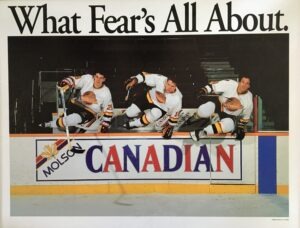

“Gino came in very raw at the beginning of his career and served a purpose as far as going out and making a statement for our team,” remembered goaltender Kirk McLean, a 2020 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “He made sure no one messed around with our star players or they were going to have to deal with him. He made a name for himself right off the bat as a physical force and one tough customer.”

“Gino really came in and gave us that stiffness, that backbone,” agreed Linden.

Less than a week after making his debut, there was another big moment. The Canucks were playing the Minnesota North Stars at the Coliseum and it was clear Gino was staying up with the team long term. The Canucks flew in Gino’s dad to watch him play. It was the first time Joseph Odjick had seen his son play in the NHL. And what’s more, late in the second period Gino scored his first NHL goal, tying the game in a 1-1 tie.

“I looked up in the stands and said, ‘Dad, this is for us!’” Gino recalled with obvious pride. “That was so touching to be able to score a goal with my dad there knowing how much effort and time he put into my hockey career. On a personal level, that was the goal that made me the most proud in my career.”

The Vancouver fans took to Gino right away, recognizing an honest player who gave his all and wore his heart on his sleeve. He played the rest of the season with the Canucks, accumulating 296 penalty minutes (fourth highest in the NHL that year) and chipping in with seven goals in 45 games. Not only was he an NHL regular, like Stan Jonathan was for him, he was also now an inspiration for young Indigenous kids all over Canada, but particularly back home in Maniwaki. Even Gino didn’t realize how big making the NHL was to his community until he returned home for the first time over the NHL All-Star break in early 1991.

“Everyone from the reserve came out,” he told Ed Willes, then of the Winnipeg Sun. “There were 300 people there. They let the kids out of school. They made pictures for me. It made me feel good. We all knew each other when I was growing up. I still carry that around with me. I’ll always carry it around.”

“Everyone from the reserve came out,” he told Ed Willes, then of the Winnipeg Sun. “There were 300 people there. They let the kids out of school. They made pictures for me. It made me feel good. We all knew each other when I was growing up. I still carry that around with me. I’ll always carry it around.”

From that first season Gino was always one of the most prevalent Canucks working in the community, supporting charities and events, and particularly making hundreds of appearances at workshops, hockey schools, and conferences to help youth in Indigenous communities around BC. Maybe the most memorable was his 800km Spiritual Journey of Healing, an 800km run through 20 Indigenous communities from Calgary to Vancouver in the summer of 1995 to raise awareness among Indigenous youth of the dangers of alcohol and drugs. To this day, Gino remains active in supporting Indigenous youth and communities throughout BC. No one could be prouder than the man who first discovered him for the Canucks.

“He’s been an inspiration to a generation of kids of all colours and ethnic backgrounds, and especially to young First Nations hockey players,” said Ron Delorme.

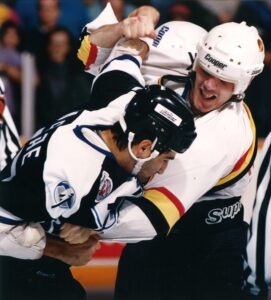

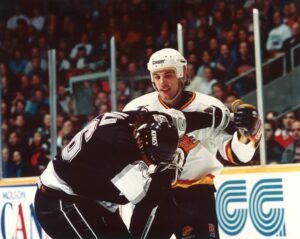

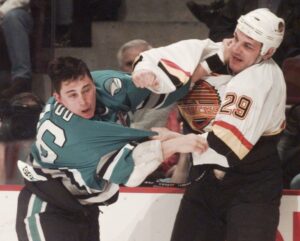

Over his eight seasons with the Canucks Gino played in 444 regular season games and dropped the gloves 129 times during the regular season plus another three times in the playoffs against some of the NHL’s heavyweight enforcers. He traded punches with everyone from Tie Domi, Marty McSorley, Stu Grimson, Dave Brown, Shane Churla, Tony Twist, Kelly Buchberger, Link Gaetz, Matthew Barnaby, and Basil McRae, among others.

“You never had an easy night when you had to fight,” said Gino. “Guys that were enforcers in the NHL, they knew what they were doing. So anybody that did the job, I had a lot of respect for because I knew it wasn’t easy work. But that was often their only role. I was fortunate enough that I had the role to create energy and score the odd goal and be part of the team and part of what’s going on, so I was really privileged that way.”

“Believe me, he rode the gauntlet his first year or so, as most of those enforcer-type guys do early in their career when you have to make a name for themselves,” said McLean. “So they’re fighting every night. And not just once, maybe twice, sometimes three times a night and, gosh, you wonder, these poor guys, the night before a game a bunch of us are out having fun and enjoying ourselves at a good meal on the road and you know that these guys are thinking about who they have to come up against the next night. It may be just one player on their team or maybe a couple players. That’s a pretty tough way to live through your career.”

About the only heavyweight Gino didn’t face was Detroit’s feared pugilist Bob Probert. It’s a dream match-up that NHL fans still salivate over. Regardless of who might have won that battle, no less than Brian Burke ranked Gino as one of the toughest fighters ever, a player who could intimidate the opposition just by his mere presence.

“Oh, no question,” emphasized McLean. “And he was an honest player, you know? I think when people sometimes hear the term ‘enforcer’ they think they’re dirty. Gino played by the code. Every now and then he would definitely get a little ticked off, but that was his competitive spirit. His role in the early years and for most of his career was to take care of the team and protect the star players.”

“I protected my teammates and got into some tussles to try and get the team going when we were flat, but everything was about the team,” Gino emphasized. “I never fought to see who was the toughest guy or for ego purposes. It was just about winning and that was why I did it.”

He would also score 47 goals and add 51 assists for 98 points with the Canucks, while accumulating 2,127 penalty minutes—a club record that still stands to this day. But his value to the team, as many teammates attest, couldn’t be measured in any statistics line. As one of the toughest, most feared enforcers in the NHL, he immediately earned the Canucks respect with opponents on the ice allowing his more skilled teammates to play their game. It was no coincidence that as Gino established himself as one of the NHL’s heavyweights, many Canucks scorers went on to have career years and the team rose in the standings through the early-to-mid-1990s.

“Gino was like a big brother,” said teammate Cliff Ronning, a 2018 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “As a smaller player trying to survive playing against giants, I always knew Gino had my back! That alone gave me confidence to perform at my best.”

“Gino was like a big brother,” said teammate Cliff Ronning, a 2018 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “As a smaller player trying to survive playing against giants, I always knew Gino had my back! That alone gave me confidence to perform at my best.”

“Just an absolutely key part of our team,” agreed McLean. “Without a doubt. Heart and soul. One heck of a guy. A wonderful teammate and he was willing to pay the price—and did pay the price—for the betterment of the team. He laid his body on the line night in, night out for the team. Whether that was to give the guys a lift or going out there to make sure the other side wasn’t taking advantage of us and he did that on a consistent basis. I’m going to tell you, I didn’t see him lose too many altercations. There would be a tie at worst for Gino.”

“He genuinely cared about people,” said Linden. “Everyone saw how he played on the ice and that was obvious but he really cared about his teammates. He loved to have fun with them, at their expense at times. He was a lot of fun. He was an awesome teammate.”

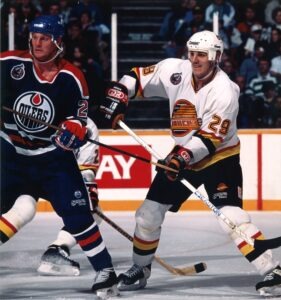

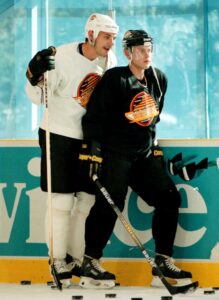

No teammate became closer to Gino than the Canucks’ first superstar, Pavel Bure ‘The Russian Rocket.’ Arriving in late 1991, Pavel and Gino quickly became inseparable friends off the ice—“We just clicked” said Gino—and as opposing teams began to take runs trying to slow Bure’s blazing speed, increasingly Quinn sent out Gino on Bure’s wing to ride shotgun for protection. Many consider his presence on and off the ice as a key factor in Bure’s success as one of the most dynamic scorers in NHL history.

“When Pavel arrived, Gino was the natural guardian for him,” said Linden. “But Pavel and Gino had such good chemistry. You think back to some of the goals that Gino scored, they were really impressive. Pavel loved to score, but Gino loved to score too. The crowd went crazy. It was just electric.”

Practicing, playing, and even training with Bure in the off-season only helped Gino develop into a more complete player.

“Pavel really helped me along to show me how to play hockey. To position yourself and whenever he had the puck inside our zone, I was always one zone ahead of him because he was so quick. We’d get a two-on-one and he’d feed me the puck for an empty net. If anybody ever messed with him or went anywhere near his time or space, I was right there sticking up for him so we had a really good relationship.”

While most enforcers were one-dimensional players playing a handful of minutes a game, Gino continued to improve and work on his game to the point where Quinn could put him out on the ice in any situation and he would contribute. No better example exists than the 1993-94 season where Gino put together a career high of 16 goals, 13 assists, and 29 points and 271 penalty minutes in 71 games.

“That was my career year. I worked out that summer with Pavel and his dad and really came into training camp in great shape. I got a chance to play with Pavel and that really helped. When you play with star players, you know you’re going to get points. You go to the net and you’re going to get rebounds or they give you the puck. It helped playing with those guys.”

“That was my career year. I worked out that summer with Pavel and his dad and really came into training camp in great shape. I got a chance to play with Pavel and that really helped. When you play with star players, you know you’re going to get points. You go to the net and you’re going to get rebounds or they give you the puck. It helped playing with those guys.”

Considering Gino put up these kinds of numbers while still acting as policeman on the ice is a remarkable performance by any standard.

“I mean how many goals did he have that one year?” asked Linden, who when told it was 16 then exclaimed, “I mean, that’s crazy! That’s legit, you know what I mean?!”

“What really impressed me the most is Gino worked on his game,” said McLean. “You have to give him credit for that. He did whatever he needed to do to stay in the NHL and in the lineup night after night. Just his development as a player from when he first arrived at training camp, that was what made me very proud of him.”

Asked to narrow down the highlight of his time with the Canucks, Gino naturally points to the Canucks 1994 run to Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final before falling to the New York Rangers at Madison Square Garden.

“Just how that team came together,” he said. “Everybody seemed to have a career year that year. Pavel scored 60 goals. Trevor had 32, I think. Cliff was almost at a point a game. Geoff Courtnall was too. Greg Adams was having another good year. We just came together in the playoffs. We eliminated Calgary the number one seed in seven games and from there the team just bonded. We were flying. It was just unbelievable.”

But as Canucks fans know all too well, Game 7 didn’t go Vancouver’s way despite the magical run up to that point. No one took that devastating loss harder than the players themselves and Gino still considers it the biggest disappointment of his career.

But as Canucks fans know all too well, Game 7 didn’t go Vancouver’s way despite the magical run up to that point. No one took that devastating loss harder than the players themselves and Gino still considers it the biggest disappointment of his career.

“Nathan Lafayette had an open net late and he hit the post. If I could change anything, that goal would go in and we’d go to overtime and it could go either way. I was young and naïve. I was like, ‘It’s okay, we’ll get there again next year.’ But we lost a bunch of players and it was really tough to get back to where we were. We got our one shot but lost in seven.”

There were memorable moments for him after that though. One included taking on seemingly the entire St. Louis Blues team while fighting bare-chested in the first round of the 1995 playoffs. The next year in the Canucks opening round playoff loss to the eventual Stanley Cup champion Colorado Avalanche in six hard-fought games, Gino scored the game-winner for the Canucks in both of their victories and was regarded as one of the best players in the series.

In 1996-97, he compiled a career-high 371 penalty minutes to lead the NHL that season. It remains the 11th highest single season total in NHL history.

In early 1998, Gino was a victim of the mass housecleaning of the turbulent Mike Keenan era, traded to the New York Islanders at the trade deadline. His first game with the Islanders ironically was against his former team the Canucks, as he literally moved his equipment down the hallway at GM Place to the visitors dressing room. Gino then fought the newest Canuck that he’d just been traded for that night—Jason Strudwick—and received a loud ovation from the Vancouver fans who had adored him the past eight seasons. And, of course, the crowd chanted his name one more time.

“GINO! GINO! GINO!”

In later seasons he played with the Philadelphia Flyers and the Montreal Canadiens, the latter particularly special.

“Montreal was just exceptional because that’s who I identified myself with when I was growing up,” he said. “I got a chance to play in front of my kids and my mom and dad, my family and friends.”

After signing a new three-year contract and working his way up to Montreal’s third line in an increased role reflecting his continued growth as a complete player, a series of concussions sadly ended his career early in 2002. Over his 12 seasons in the NHL, Gino finished with 64 goals, 73 assists, 137 points, and 2,567 penalty minutes in 605 regular season games.

“The biggest compliment I had was a reporter said that ‘Gino plays out there like he’s having fun, like he’d play for free.’ I wouldn’t play for free [laughs], but I really enjoyed myself. I always had a smile while playing. I loved being part of a group and competing and trying to win hockey games. That was so much fun to be in the NHL. And certainly I had my greatest years in Vancouver, that’s for sure.”

In 2003, he moved back to Vancouver to live where he has made his home ever since.

“I really enjoy British Columbia. It’s never too hot, never too cold. I just got used to the Vancouver weather and I don’t want to be anywhere else. I love the people and love the city.”

“He is now British Columbia’s adopted son,” noted Delorme, whom Gino remains close to.

His close relationship with the fans and people of BC was never more obvious than in 2014 when it was announced that Gino had a rare terminal disease known as AL amyloidosis and that he had just months at most left to live. Hundreds of fans gathered outside Vancouver General Hospital chanting his name in support. Looking unusually frail and gaunt, Gino appeared at the hospital entrance in a wheelchair to thank those gathered. He’d battled every step of the way to the NHL and now was no different, as he underwent an experimental treatment in Ottawa and the condition went into remission. Eight years later he is in remarkably good health now and appreciates every day.

“I got a second lease on life,” he said, “and I live life to the fullest.”

In recognition of his NHL career and his many years of contributions giving back to Indigenous communities, Gino was the 2015 recipient of the Indspire Award in the sports category, the highest honour the Canadian Indigenous community bestows upon an individual.

In recognition of his NHL career and his many years of contributions giving back to Indigenous communities, Gino was the 2015 recipient of the Indspire Award in the sports category, the highest honour the Canadian Indigenous community bestows upon an individual.

More recently, a grassroots movement to see Gino honoured in the Canucks Ring of Honour at Rogers Arena has gathered momentum. His induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame will no doubt help that cause.

Looking back on it all, Gino stands proud today of what he has been able to accomplish.

“Just being able to make a career out of it, showing First Nations youth if you work hard and you believe in yourself, if you get a chance, it doesn’t matter if you’re white, black, Chinese or First Nations, they don’t look at colour, they look at your work ethic and what you’re able to provide to the team. Whether it be a carpenter or a plumber or a doctor or a nurse, whatever you want to be, you can do it.”

When Gino is formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame on June 9th, you can bet the “Gino! Gino!” chants will ring around the ballroom at the Vancouver Convention Centre.

“It’s amazing because I never expected it. My friend Peter Leech nominated me and he didn’t tell me and all of sudden I get a call that I was inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame. I said, ‘What?! Really?!’ That was a special moment, that’s for sure, made me really proud. My family is really proud. That really makes me happy that my family appreciates it as much as I do. Just such an honour to be inducted.”

As part of the Class of 2021, Gino Odjick will be formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Athlete category at the annual Induction Gala to be held June 9, 2022 at the Vancouver Convention Centre.