Eli Pasquale: An Unbreakable Will – 2021 Inductee Spotlight

June 6, 2022By Jason Beck

Question: who was the most competitive athlete in BC sport history?

Who had the most drive? The strongest will to succeed?

Although impossible to definitively answer, many strong contenders certainly spring to mind. But allow me to add a new name who probably hasn’t been given his due to the mix:

Eli Pasquale.

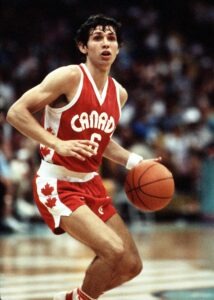

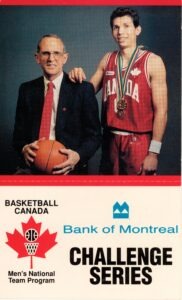

Through the 1980s Eli was Canada’s best basketball player and one of the world’s best point guards in international play. “Steve Nash before Steve Nash” some have called him. There’s a story Ken Shields, Eli’s long-time coach at the University of Victoria and with the Canadian men’s national basketball team, likes to share that illustrates better than any other how badly Eli wanted to win, to improve, to be the best.

It’s September 1979. Nineteen-year-old Eli has just arrived in Victoria from his home in Sudbury, Ontario to begin school at UVic and play for the Vikings, the men’s basketball team coached by Shields. At the end of the first practice, as they often would, the whole team and everybody trying out went on a long run.

“Ian Hyde-Lay, our captain, was usually the winner,” said Shields. “He took pride in being the winner. So he won the first day. Eli came in second. [long pause] Eli never came in second again in five years. He won every conditioning drill that we ran including those runs. Never got beat in another run in five years.”

You can be the fittest athlete, but everyone, even the elite, have off days. Maybe you’re not feeling great, didn’t sleep well, feeling tired or sore, carrying a nagging injury. So you take a day off or ease up a bit.

You can be the fittest athlete, but everyone, even the elite, have off days. Maybe you’re not feeling great, didn’t sleep well, feeling tired or sore, carrying a nagging injury. So you take a day off or ease up a bit.

Not Eli.

“He never had an off day,” said Shields. “He never had one.”

And it should be pointed out that over those five years Eli was UVic’s point guard running the show, the Vikings won five straight CIAU (now CIS) national championships.

“When you have a guy like Eli who does that innately, setting the standard,” explained Shields, “he automatically moves the competitive guys out of their comfort zones because now they have to try to keep up with him. It raises the overall level of commitment in your practices and your team. He didn’t do it to show off. He never put anybody down or thumped his chest about doing that. He just did it because he could. And if he could, he should. If he was going to be a leader on the team, he led primarily by example. That gained tremendous respect from his teammates and from the coaching staff.”

“He was the most competitive person I ever met—next to Ken Shields—and that’s saying something,” chuckled Chris Hebb of his UVic teammate. “There was no second-best with Eli. It was always full-on competition. It was a very rare occasion when Eli’s team didn’t win. He would do whatever it took to win. There was this resolve in him that was substantial and all I ever saw it do is get more and more pronounced.”

That resolve, competitive fire, drive, will—whatever you want to call it—would propel Eli to become one of the best basketball players this country has ever produced.

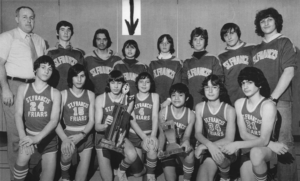

Eli was born in Sudbury, Ontario in 1960 to blue collar Italian-born immigrants. His father Antonio was a bricklayer, while his mother Adriana was an excellent cook known for her delicious pasta which she often made at Cassio’s restaurant in Sudbury. Growing up in Sudbury’s tight-knit Italian neighbourhood known as Gatchel, Eli played hockey and soccer but basketball was his true love. When he was 15 he watched the Canadian men’s basketball team defeat the Soviet Union live on CBC, the first time a game featuring the national team was broadcast nation-wide and it seemed to ignite something within him.

“For whatever reason, it just hit me,” he told Dave Feschuk and Michael Grange for their 2014 book, Steve Nash: The Unlikely Ascent of a Superstar. “I want to go to the Olympics, I want to play for Canada. So that was the start of that.”

“For whatever reason, it just hit me,” he told Dave Feschuk and Michael Grange for their 2014 book, Steve Nash: The Unlikely Ascent of a Superstar. “I want to go to the Olympics, I want to play for Canada. So that was the start of that.”

It was around that same time that Eli first met Shields, likely the only man other than his father who would have such massive influence over the direction of his life. Shields was coaching Laurentian University’s men’s basketball team in Sudbury at the time.

“Eli came to the first basketball camp I ever ran at Laurentian University,” remembered Shields.

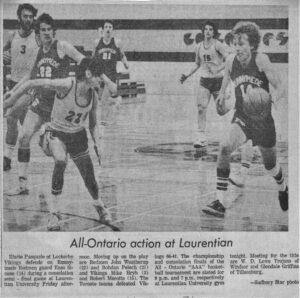

Still a student at Lockerby Composite School, Eli began hanging around Laurentian’s gym a lot in the summer shooting hoops.

“Eventually he got involved in our scrimmages,” said Shields. “They were very, very competitive scrimmages—I actually played in them because I was still young too—but Eli learned he could play. He did well. We became friends.”

Shields noticed immediately the unique talent and drive in Eli and made a mental note to keep tabs on this skinny high schooler as a future university prospect. What he couldn’t have known then was how deeply that drive was already imprinted on young Eli. Upon Eli’s passing in 2019, Sportsnet’s Michael Grange related this remarkable anecdote edited for length:

“It was a hot summer day in Sudbury, and Eli Pasquale and his friends were doing what they always did: playing pick-up hoops in the gym at Lockerby Composite School. There was a little extra spice in the scrimmages that day. Visiting from Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., was Dave Zanatta another high-end high school talent who had made the four-hour trip to find some competition. After a couple of hours and many buckets of sweat, someone suggested heading to the lake for a swim. Pasquale went along, Zanatta stayed. The group returned from their swim later in the afternoon to play some more and the rolled into the gym to find Zanatta – who went on to star at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay – still working on his game.

“It was a moment that changed Pasquale’s life and arguably Canadian basketball.

“That was it, I said ‘never again’,” Pasquale recalled. “I made a decision at that point – I think in Grade 11 — that never again was I going to let anyone else play more hours than I do, and I don’t think many did, to be honest. Kids laugh, but they don’t realize it. I put in six to eight hours a day. That’s what I did in the summertime. There was no question, I put my time in.”

When Shields decided to leave Laurentian in 1978 to come back home to BC and coach at UVic, Eli came to see him and say goodbye.

“He said, ‘Someday I want to come and play for you,’” recalled Shields, which must have been music to his ears as Eli was already a bona fide high school star and a member of the Canadian junior national team at just age 17.

They kept in touch and later that year Shields arranged to have Eli’s Lockerby high school team travel out to Victoria to play in the Oak Bay Christmas tournament.

“I wanted to get him out to see the campus and visit,” said Shields. “I knew he’d like Victoria.”

Eli and his Lockerby teammates won the tournament, fittingly on a last-second buzzer-beating shot by Eli to take the final game. That was the first time future UVic teammate Hebb saw Eli play.

“It was shocking the skill level and the speed and just the dynamism on the court,” recalled Hebb. “You just couldn’t take your eyes off him because he was in complete control of the play. In terms of the level of skill as a grade 12 player, it was up to the level where Steve Nash got to. It was just another level of maturity that was not expected in a high school player. He brought that to UVic.”

Shields was obviously doing his best to recruit Eli to UVic despite the fact Eli’s hometown Laurentian squad that Shields had just left also wanted him badly. Laurentian was a top team too, Shields having coached them to a fourth-place finish at CIAU nationals in 1977-78.

Shields was obviously doing his best to recruit Eli to UVic despite the fact Eli’s hometown Laurentian squad that Shields had just left also wanted him badly. Laurentian was a top team too, Shields having coached them to a fourth-place finish at CIAU nationals in 1977-78.

“I felt badly and it was tough for me, but Eli and I had a long connection and he ended up coming,” said Shields. “The rest was history.”

Yeah, history. Eli made a lot of that at UVic.

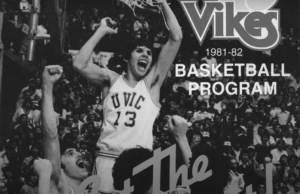

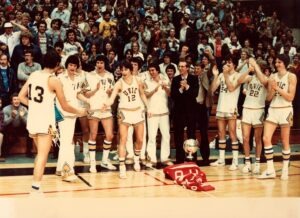

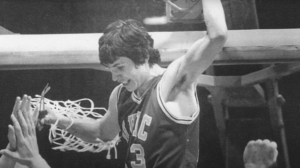

During his remarkable five years at UVic from 1979-80 to 1983-84, Eli led the Vikings to five consecutive CIAU national championships. The Vikings would go on to win two more after Eli graduated during a record-breaking seven-year dynasty. Eli is believed to be the first athlete in Canadian university sport history to win five national championships in their five years of eligibility. He remains one of only a handful of athletes to have accomplished this today.

“That pretty rarified air in Canadian university sports,” confirmed Howard Kelsey, a 2012 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee and a teammate of Eli’s on the Canadian national team.

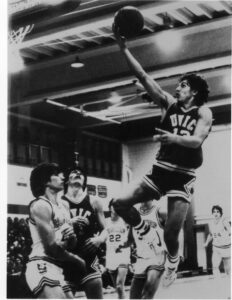

Eli also won just about every accolade possible in that five-year span when he called UVic’s McKinnon Gym home. In 1984, he received the Mike Moser Memorial Trophy as the CIAU’s outstanding men’s basketball player. He was named a CIAU First Team All-Canadian three times in 1982, 1983, and 1984. Twice he was named the CIAU national tournament MVP. He was named a Canada West Conference First Team All-Star all five of his years playing. He was named the BC University Athlete of the Year in 1982. Twice he was named UVic’s top male athlete. He ended his five years of eligibility at UVic as the university’s all-time leading men’s scorer. Later on, in 2005 he would have his number 13 jersey retired at UVic, one of only three individuals in the university’s history to be so honoured.

“In the history of the Canada West conference, there’s nobody that had the impact that Eli did,” said Shields. “No one close. He made us into a formidable operation just with his tenacity and his leadership. His will to win. His fierce competitiveness.”

Ian Hyde-Lay’s last season with the Vikings in 1979-80 was the first for Eli, barely 19 and joining an experienced squad that had made the CIAU national final the year before.

Ian Hyde-Lay’s last season with the Vikings in 1979-80 was the first for Eli, barely 19 and joining an experienced squad that had made the CIAU national final the year before.

“It was so obvious immediately that he was tremendously skilled and competitive,” remembered Hyde-Lay. “He very quickly established himself as a player on a pretty senior-laden team. And he became a huge part of what was the first of seven straight UVIC national championship teams.”

Eli began his rookie season mostly coming off the bench, but when Hyde-Lay was injured late in the season, Eli stepped in as the starting point guard for the first time.

“He just took it in stride,” recalled Hebb with amazement in his voice. “We didn’t miss a beat. He had extraordinary maturity in that role.”

The 1979-80 UVic team’s motto was ‘You can’t stop a train!’ and the Vikings steamed to UVic’s first-ever CIAU national basketball championship. That team was the first UVic team inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 2020.

Into his second and third seasons with the Vikings, Eli adapted to the increased speed and strength of opponents—as well as the increased attention he was now being paid by defenders. Already a spectacular driver of the basketball to the rim, he now rounded out his game with an effective pull-up jumper. He also became a strong leader on the team. After Hyde-Lay graduated and went away for a couple years, he came back to Victoria and served as one of Shields’ assistant coaches beginning in 1983-84. The changes he noticed in Eli were shocking.

“His game had exploded in every way,” recalled Hyde-Lay. “He was the best university player in the country. All the parts of his game were excellent. An outstanding defender. Tremendous passer. Could score. A wizard ballhandler. So competitive and fit.”

What is often overlooked in that UVic dynasty is the pressure that the returning players, especially Eli, shouldered as they fought to stay on top. If it’s hard to get to the top, it’s even harder to stay there.

“We had a bullseye on us,” confirmed Shields. “If we didn’t bring our best, there were teams that would take us down because it meant so much if they beat UVic. That wasn’t a burden. That was a challenge and when you have guys like Eli, he met that challenge every day in practice. He was number one every single time.”

“We had a bullseye on us,” confirmed Shields. “If we didn’t bring our best, there were teams that would take us down because it meant so much if they beat UVic. That wasn’t a burden. That was a challenge and when you have guys like Eli, he met that challenge every day in practice. He was number one every single time.”

Despite the pressure, nothing ever seemed to get to Eli.

“He was just so positive,” said Hyde-Lay. “Everything was ‘Bene, paisan. Bene, bene, bene,’ always good.”

Although he maintained strong ties to Sudbury, Victoria and BC quickly became home for Eli. He convinced his younger brother Vito to also come out to UVic, where he played on three of the Vikings national championship squads. It was where he later met and married Karen, his wife, and they raised their two boys Isiah and Manny.

In fact, Eli had only been in Victoria for less than two years when he chose to play for Team BC, coached by Shields, at the 1981 Canada Games in Thunder Bay, Ontario.

“Eli could have played for Ontario, but he played for us,” said Shields. “We played Ontario in the final in a really tough game and we won it. Ontario was ‘P.O.-ed,’ I want to tell you. Their coach tried to have us disqualified because we had national team players like Eli. But Eli didn’t have any qualms about it. He was BC. And he won a gold medal for BC playing at the Canada Games.”

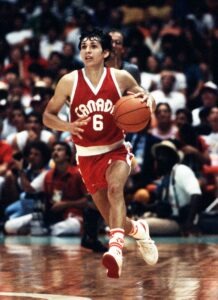

Eli joined coach Jack Donohue’s Canadian squad for the first time in 1981 and remained a pillar of the national team for the next 12 years eventually becoming the team’s co-captain alongside Jay Triano.

“For Canada, at the end of the day, he was the quintessential point guard,” said Hebb. “He controlled the ball. He controlled the plays. And he got the ball where it needed to be in order for the team to be successful.”

You can argue it was the most successful era in Canadian men’s basketball history. With Eli leading the way alongside Triano, Howard Kelsey, fellow UVic teammates Gerald Kazanowski and Greg Wiltjer, and NBA veteran Bill Wennington, Canada spent much of the decade ranked in the top five in the world.

“Not yet has Canada rivalled it since,” confirmed Kelsey. “You can have all the NBA guys in the world, but you gotta know how to win.”

Eli would help Canada qualify for three FIBA World Championship tournaments (1982, 1986, 1990) with a sixth-place finish in 1982 in Colombia Canada’s best result. At the Pan American Games, Canada would finish fourth in 1983 and fifth in 1987. With Eli quarterbacking the backcourt, Canada qualified for both the 1984 and 1988 Olympics finishing fourth in the former and sixth in the latter. In 1984 in Los Angeles the Canadians were knocked out in the semifinals by the host Americans but battled a very strong Yugoslavian squad in the bronze medal game before falling 88-82.

“We probably should have had a bronze medal,” said Kelsey. “We came up just a few points short against Yugoslavia with Dražen Petrović.”

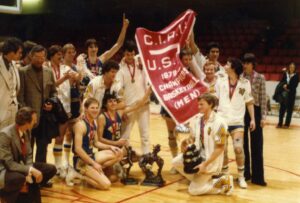

The high-water mark for Canadian men’s basketball in that era was undoubtedly the 1983 Summer Universiade held in Edmonton at a time when most countries still sent their actual first-string national teams to play in this competition. Eli was at his absolute best in the semifinals against an American team that featured future NBA legends Charles Barkley and Karl Malone. Outplaying the highly touted Johnny Dawkins from Duke, Eli scored a team-leading 13 points in the game’s second half as Canada downed the Americans 85-77 as the game was broadcast nationally on both CBS in the US and CBC in Canada. No one played better than Eli when the game was on the line late.

“He had the game completely under control,” said Kelsey. “When you’re the point guard and you can handle Johnny Dawkins and the rest of that heat and you’re up on Team USA, which almost never happens, that would be my strongest memory of him. It vaulted us.”

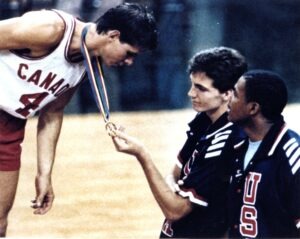

Canada went on to win the Universiade gold medal defeating Yugoslavia 83-68 in the final. In Canadian basketball circles, it’s revered as sort of a ‘Miracle on Ice’ story that took place on the hardwood but is hardly known in wider Canadian sport circles. As Eli, Kelsey, and their Canadian teammates were up on the podium receiving their gold medals, it led to one of the great photos in Canadian basketball history.

“Rarely are we on the gold medal podium and rarely is the US on the bronze,” said Kelsey, “so Barkley actually pulled me and said, ‘Hey, can I see your medal?’ I leaned down and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch took the picture and then it got shot all around before the Internet. It’s an iconic picture for Canada in FIBA basketball.”

Two years later in Kobe, Japan, Eli and his Canadian teammates emerged with a Universiade bronze medal after edging Bulgaria 96-95 in the bronze medal game.

Eli’s international play in the early 1980s began turning heads and he was drafted in the fifth round, 106th overall in the 1984 NBA Draft by the Seattle Supersonics. While trying to make the Sonics final roster, he played well in three exhibition games including one in Vancouver, but it came down to Eli and Danny Young, another point guard Seattle had drafted higher in the second round of the 1984 Draft.

Eli’s international play in the early 1980s began turning heads and he was drafted in the fifth round, 106th overall in the 1984 NBA Draft by the Seattle Supersonics. While trying to make the Sonics final roster, he played well in three exhibition games including one in Vancouver, but it came down to Eli and Danny Young, another point guard Seattle had drafted higher in the second round of the 1984 Draft.

“They would have had to release Young if they’d kept Eli,” explained Shields. “That wouldn’t have looked great. Even though Eli was playing very well and all the veterans were surprised when they released him.”

The following year Eli nearly made the Chicago Bulls, who were looking for someone to play in the backcourt beside Michael Jordan. Eli had impressed the Bulls, but ultimately, they went with American John Paxon. Eli was their final cut. At a time when few foreigners were given a chance in the NBA, it proved to be his last opportunity. Those who knew him best are convinced that if he came along in a later era, Eli would have found a place in the NBA.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt,” said Hebb.

“No question,” said Hyde-Lay.

“In today’s world, he’d have been in the NBA,” agreed Shields.

Eli did play in the Los Angeles summer pro league and professionally in Argentina in 1986, Germany in 1989, and Switzerland in 1990.

He may not have made it himself, but Eli played a major role in helping along the next great Canadian point guard who did, and to whom he is most often compared, Steve Nash.

“Eli was a giant,” said Nash in 2019. “He was my hero. His passion and commitment were an incredible education for me. Eli’s competitive fire was world class. He should have played in the NBA, but times were different back then.”

In a remarkable parallel to Eli’s own beginnings years earlier at Laurentian, a young Nash could often be found at McKinnon Gym watching Eli play for UVic and the national team. It wasn’t long before he was playing on the same court as his hero. When Nash was a skinny junior high student at Mount Douglas Secondary, Shields, by then coach of the national team, invited him to join a national team scrimmage in the Mount Doug gym. Shields noted that Nash “didn’t look out of place.” Eli took note as well and began working with the young hoop heir apparent.

In a remarkable parallel to Eli’s own beginnings years earlier at Laurentian, a young Nash could often be found at McKinnon Gym watching Eli play for UVic and the national team. It wasn’t long before he was playing on the same court as his hero. When Nash was a skinny junior high student at Mount Douglas Secondary, Shields, by then coach of the national team, invited him to join a national team scrimmage in the Mount Doug gym. Shields noted that Nash “didn’t look out of place.” Eli took note as well and began working with the young hoop heir apparent.

“I can’t put into words what it was like to play your hero one-on-one,” Nash said.

And when it was time for Nash to get serious about basketball, it was Eli who gave him the push he needed.

“I’ll never forget coaching the little kids at his basketball camp as a 17-year-old and Eli giving me a ride home one day,” Nash told Doug Smith of the Toronto Star in 2019. “On the drive he asked me if I wanted to play in the NBA and I said ‘yes, of course,’ knowing I did but knowing the odds. He told me if I wanted to make it, I had to decide now and commit to it. ‘Don’t wait,’ he said. For the captain of our national team to take an interest and a belief in me was incredibly powerful and I’ll always be grateful.”

Nash, of course, went on to an 18-year NBA career in which he was named an NBA All-Star eight times, a two-time winner of the NBA MVP award, and induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame. He did it all while wearing the same jersey number 13 as Eli, which was no coincidence.

Just as Nash’s star was beginning to rise in the early 1990s, Eli’s career came to a sudden end. Playing in an exhibition tournament in Puerto Rico in 1992, Canadian teammate Bill Wennington collided with an American player and accidentally fell on Eli’s leg, snapping his ankle.

“It was an unavoidable fall and those things happen,” said Shields. “I knew when I saw it, I thought ‘Oh my god, this is not good’ and I ran out. And Eli looked at me and he just shook his head. He said, ‘My leg’s broken.’”

Without their captain and point guard, Canada struggled at the Tournament of the Americas in Portland shortly afterward and failed to qualify for the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona.

“I know if Eli was there we never would have lost,” said Shields. “We failed to make the Olympics. It was the biggest disappointment of my coaching career and it all revolved around Eli getting his leg broken. I felt so sorry for him. All the years that he put in and he would have been going to his third Olympics. Went down the drain. It was tragic.”

Canada wouldn’t qualify again for the Olympics until 2000 when Nash emerged on the scene.

Eli would take five years off from the game but made an unlikely surprise return to the national team in 1997 at age 37, playing at the Tournament of the Americas in Uruguay and helping Canada to a fifth-place finish and qualification for the 1998 FIBA World Championships. He retired for good after that.

By then Shields had departed the Canadian national team as well. He remained friends with Eli for life.

“Eli was like an Arabian horse,” he said. “He was high-strung. We weren’t always on the same page, but it never got in the way of our friendship. We had a rule. If it happened on the court, it stayed on the court. We walk off the court and everybody’s friends.”

“Eli was like an Arabian horse,” he said. “He was high-strung. We weren’t always on the same page, but it never got in the way of our friendship. We had a rule. If it happened on the court, it stayed on the court. We walk off the court and everybody’s friends.”

So was Eli the best player Shields coached in his own remarkable hall of fame career?

“Steve and Eli,” Shields answered quickly. “Those two were probably the best. They might not have been the best athletically. We might have had better athletes. But they were the best overall.”

In retirement, Eli focused his time on his young family and his immensely popular basketball camps. Beginning in 1985 and right up to his passing in 2019, he ran youth development camps all over BC, but particularly in Victoria, even involving his sons in running them as they got older. Thousands of BC kids got their start in basketball through Eli’s camps.

“For Eli to have spent so many years after running camps and teaching kids basketball comes as no shock to me,” said Hebb. “The kids that he must have influenced over those years are legendary. He gave back. He didn’t just take. He gave back.”

“He poured back a lot of his own time into the camps and into helping young kids get an opportunity, which is often all that’s needed,” agreed Hyde-Lay. “He appreciated the opportunity he’d been given by Shields as a young high school player in Sudbury and so he made sure he paid back.”

Sadly, this story has a tragic end. In 2019, at the age of just 59, Eli discovered he had an aggressive form of esophageal cancer, which claimed his life later in the year.

“The way he fought his cancer was just so courageous,” said Hyde-Lay. “Everything was still, ‘Bene, bene.’ The last time I saw him, which was just a few weeks before he passed away, there was no self-pity. All he was doing was asking me how I was doing, how my family was doing. Rather than the other way around, even though we probably knew that meeting was going to be our last. For someone just so capable, fit, and strong to be felled by cancer at such a young age, is just so unfair.”

“The way he fought his cancer was just so courageous,” said Hyde-Lay. “Everything was still, ‘Bene, bene.’ The last time I saw him, which was just a few weeks before he passed away, there was no self-pity. All he was doing was asking me how I was doing, how my family was doing. Rather than the other way around, even though we probably knew that meeting was going to be our last. For someone just so capable, fit, and strong to be felled by cancer at such a young age, is just so unfair.”

“In coaching, the real achievements are in the relationships you develop and Eli and I had a very close relationship,” said Shields. “I was so devastated when I learned of his medical condition. I tear up whenever I think of it. [long pause] The last time I saw him, he said some really nice things and I said some nice things. And we told each other how much we loved each other. You’re like a dad. You never want one of your players to pass before you do, especially one like Eli with our long, long connection to one another. To have a treasured relationship with him that I have is just special. So special. I’m so lucky, blessed really, to have had a totally true, honest, and trusting relationship with guys like him. Those are the important things.”

When a celebration of life was held at McKinnon Gym in November 2019, hundreds attended and many more tuned in to the livestream from around the world.

“When we were organizing it, I phoned Steve and asked him if he would speak at the event,” recalled Shields. “Without even one shred of hesitation he said yes. Didn’t even give him the date. He said, ‘Yes, I’ll be there.’ As it turned out, it was on his son’s birthday and he was there. Eli meant a lot to Steve.”

Eli was inducted into the Canadian Basketball Hall of Fame in 2003, the Basketball BC Hall of Fame and UVic Sports Hall of Fame in 2004, the Sudbury Sports Hall of Fame in 2008, and the Greater Victoria Sports Hall of Fame in 2014. His BC Sports Hall of Fame induction will make it hall of fame number six.

“To me, it’s where he belongs,” summed up Shields.

“To me, it’s where he belongs,” summed up Shields.

“I think it’s tremendous,” agreed Hyde-Lay. “So well deserved. He’ll be watching somewhere.”

As part of the Class of 2021, Eli Pasquale will be formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Athlete category at the annual Induction Gala to be held June 9, 2022 at the Vancouver Convention Centre.