David Cox: Serving Up Sport Psychology – 2021 Inductee Spotlight

June 2, 2022By Jason Beck

David Cox might own one of the most impressive office bulletin boards of any individual in BC sport.

As an internationally recognized sports psychologist who over the past forty years has worked with an amazing resume of elite Canadian athletes, teams, and organizations perhaps it’s not so surprising.

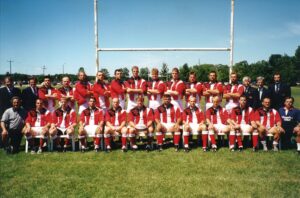

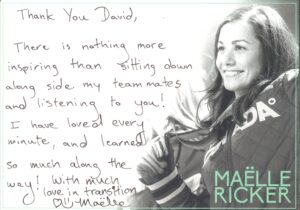

In one corner there’s a signed thank-you from Olympic gold medal-winning snowboarder Maelle Ricker. In another a signed photo from Canadian basketball legend Steve Nash. Over there is one from the Man in Motion himself Rick Hansen. There are several of David with Grant Connell, one of Canada’s greatest tennis players. Team photos signed to David from the world champion Kelley Law and Kelly Scott curling rinks, the Vancouver 86ers and Whitecaps, the Canadian national rugby team, Canada’s Davis Cup tennis team, the Vancouver Canucks. And then there is a tangle of accreditation passes from events all over the world where he has coached and supported athletes at: several Olympics, Wimbledon, and multiple world championships in various sports. And this is just scratching the surface.

Not only is David the first sports psychologist to be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame, but you can make the argument that rarely has any individual entered a hall of fame in which that person has worked with so many of that Hall of Fame’s past inductees during their own career. Connections to a few are not uncommon, but we’re talking dozens here. You could literally open a wing of any hall of fame in Canada showcasing those athletes and teams he has helped win at the highest levels of international and professional competition. It’s quite remarkable and if anything, it reflects the way David has impacted so many areas of BC and Canadian sport in so many different roles.

Not only is David the first sports psychologist to be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame, but you can make the argument that rarely has any individual entered a hall of fame in which that person has worked with so many of that Hall of Fame’s past inductees during their own career. Connections to a few are not uncommon, but we’re talking dozens here. You could literally open a wing of any hall of fame in Canada showcasing those athletes and teams he has helped win at the highest levels of international and professional competition. It’s quite remarkable and if anything, it reflects the way David has impacted so many areas of BC and Canadian sport in so many different roles.

“I’m very, very fortunate,” David said in a recent phone interview from his family home in Summerland. “It’s such a privilege to work with these athletes. You think, ‘My gosh, I got to participate in this.’ I’m a little piece of what happened here. I’ve got a great job. I love what I do. It’s the reason I’m still doing it.”

Maybe Rick Celebrini, a former Vancouver 86er David worked with as an athlete and currently the Golden State Warriors director of sports medicine and performance, put it best about his mentor.

“David has an incredible passion for sport,” Celebrini said. “He is equally impassioned giving a talk to the young tennis players within Tennis Canada as he is with the Vancouver Canucks. He is truly one of the icons of our sports community and his energy and passion has only grown through the many, many years of service to the BC sports scene.”

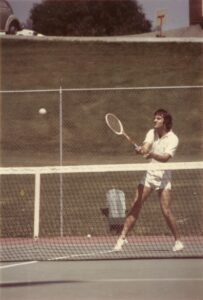

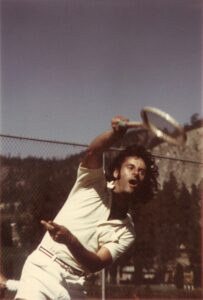

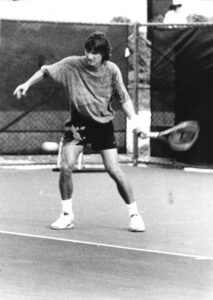

David was born and raised in Vancouver except for a brief period when his family lived in Toronto when he was quite young. His earliest memories in sport revolve around playing soccer. He later played rugby tennis, track, and basketball while attending Lord Byng High School in Vancouver, but it was his introduction to tennis at age 11 at the Jericho Tennis Club that proved the most significant.

“That was one of the greatest things that ever happened to me because it really changed my life in terms of athletics,” recalled David. “I started to play tennis and I loved the game.”

He worked hard at tennis and by his mid-teens had developed into one of BC’s top junior players. At age 18 he made the final of the Stanley Park Open. Upon graduating from high school he was awarded a small basketball scholarship to play at UBC, but it was tennis that he actually ended up playing at university. By the time David had obtained a degree in English and was working on a master’s degree in clinical psychology, he was coaching the UBC tennis team. He also later completed his PhD in clinical psychology at UBC.

In a way, David stayed in the family business. His father was also a psychologist, who worked at Shaughnessy Veterans Hospital, then UBC, and finally Langara College.

In a way, David stayed in the family business. His father was also a psychologist, who worked at Shaughnessy Veterans Hospital, then UBC, and finally Langara College.

“I think it did play a role,” he acknowledged. “There’s a thing in psychology called reaction formation where you want to do the opposite, so I think at some level I thought I’d never go into psychology. But I took a year away and thought about what I wanted to do, and I don’t know how you work these things out, but I felt a strength of mine was verbal and so I just decided it was what I wanted to do.”

After his long run at UBC, David moved to the U.K. where he did three years of post-doctoral work at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, studying with one of the great psychologists of the time, Professor Hans Eysenck.

“The reason I went was because I wanted to study with Eysenck as I was very impressed with his work,” David recalled. “But when I got there I discovered that my abilities as a tennis player were important to him. He needed a doubles partner for the tennis matches on the courts at the Maudsley Hospital. We formed a successful partnership.”

While in London, David began his studies in the field of human performance, particularly with the military, an early harbinger of his sport psychology focus that came later. He noted in our interview that recently the American Psychological Association took their division of sport psychology and changed it to the division of sport and performance psychology.

“The implication being, that this is not only sport, this is human performance,” he explained. “Any situation where the consequences of your actions have meaning, in other words where the outcome makes a difference, where there’s something attached to doing a good job, whether it’s working with the police or the military or athletes or public speakers. Most people want to do well, but their emotions get in their way. They try too hard. Their very desire to do better is getting in the way of performing well. Much of what I deal with is helping people cope with being over-motivated. We use strategies like emotional control, attentional focus, self-talk, imagery, breathing techniques, relaxation, mindfulness, and goal setting.”

When David returned to Vancouver in 1981, two things happened that set the dual paths that would largely shape his career in psychology.

One was taking a limited term position teaching at Simon Fraser University. He did that until 1986 when he secured a tenure track position. “The rest is history,” he said. “This has been my life at Simon Fraser and it was everything I could have hoped for.”

David continues to work with students and teach courses at SFU today as a professor in the clinical psychology program in the department of psychology.

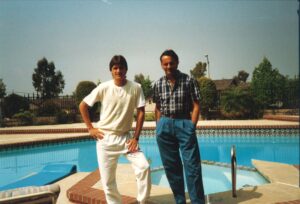

The other turning point upon David’s return to Vancouver was that he met a 15-year-old hockey player and swimmer at the North Shore Winter Club whose name was Grant Connell. Connell, of course, would develop into one of Canada’s greatest tennis players earning the number one world doubles ranking in 1993. He would also be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 1999.

The other turning point upon David’s return to Vancouver was that he met a 15-year-old hockey player and swimmer at the North Shore Winter Club whose name was Grant Connell. Connell, of course, would develop into one of Canada’s greatest tennis players earning the number one world doubles ranking in 1993. He would also be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 1999.

Still an excellent player himself, David began working with Grant on the court as well as off. It was the beginning of a transition for him, moving more into the sport psychology realm.

“I was working with Grant, so I had this incredible practice partner,” he recalled. “We trained together a lot. We spent thousands of hours on the tennis court. I worked with him throughout his career and we’re still very close today.”

You often don’t think of a sport psychologist as also being a very good athlete themselves. Many of us jump straight to the well-worn cliché of the bookish shrink wearing a tweed sweater and spending most of their day in a leather chair surrounded by thick books. That wasn’t David, whose passion for sport is obvious to anyone entering his orbit. When Connell was the top ranked singles player in Canada in the mid-1990s, David at age 40 was still a nationally ranked player. But this is part of what made David so unique and so effective when working with his athletes. Not only could he relate, but in some cases he could even demonstrate a technical skill himself or provide examples from his own experience that would carry more weight with an athlete than someone talking theory from a textbook. Plus, it was obvious to anyone that he loved sport and psychology equally and this love was infectious to others.

“I’m a big fan of excellence,” he said. “What are the things that people have who achieve excellence? What’s the key? Excellence is determined by opportunity. Opportunity to train and work. Novak Djokovic started playing tennis in an empty swimming pool in Serbia. You must have training, support, motivation. But the two big issues are you must have belief and you must have work ethic. So what’s the key that binds all this together? What’s the essence? The crucial issue is you must have a passion for what you do. Passion is huge.”

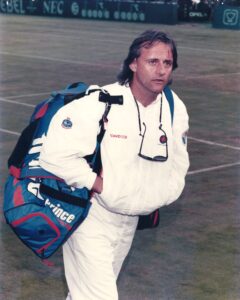

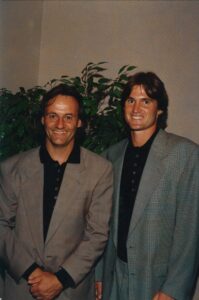

When Grant became a touring professional, David often went along with him as the first travelling sports psychologist on the ATP Tour. Along with winning 22 ATP doubles titles, Connell advanced to three Wimbledon finals with David coaching. Few stages in sport draw more pressure than center court at Wimbledon.

When Grant became a touring professional, David often went along with him as the first travelling sports psychologist on the ATP Tour. Along with winning 22 ATP doubles titles, Connell advanced to three Wimbledon finals with David coaching. Few stages in sport draw more pressure than center court at Wimbledon.

“That’s a pretty intense environment,” David said. “I remember being in the locker room before Grant’s first Wimbledon final, in what is the cathedral of tennis. I was sitting talking with Connell and his partner Patrick Galbraith before they went out to play the final against Todd Woodbridge and Mark Woodforde, the Australians. They were also there with seven or eight of the greatest Australian tennis players ever, the legacy of Australian tennis sitting and talking to them I look over at their coach Ray Ruffels and say something like, ‘Come on Ray, this isn’t fair. Send me two of those guys at least!’ As I recall he laughed and said, ‘No bloody way, mate!’”

No one appreciated having someone like David to call on when needed more than Connell.

“David’s work was the key to me being a top international player and achieving a number one world ranking in men’s doubles,” he said in 2020. “When David travelled with me on the tour, we achieved more firsts for Canadians in tennis than any other era.”

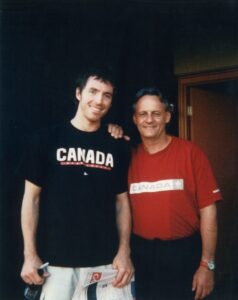

Seeing the work David was doing with young Grant early on, Tennis Canada brought David onto their staff in 1983 working out of the Western Regional Tennis Centre in Vancouver to work with all Tennis Canada athletes, including the Davis Cup and Federation Cup (now the Billie Jean Cup) high performance teams.

“That’s really where I started to make that transition to focusing more on sport psychology issues and developing my skills as a sport psychologist.”

Over the next four decades David supported Tennis Canada at 22 Davis Cup ties all over the world. This included milestone highs like reaching the World Group for the first time in 1991. It was at a Tennis Canada development camp in Toronto just over ten years ago that he first met two youngsters named Felix Auger-Aliassime and Denis Shapovalov.

David was also there for a rollercoaster ride in 1992 at Vancouver’s PNE Agrodome working with a 19-year-old Daniel Nestor, ranked 238th in the world, who took down the world’s number-one-ranked player Stefan Edberg in one of Canada’s greatest tennis upsets. Canada was leading the Davis Cup tie 2-0 before Sweden rallied with three straight wins to take the victory.

“We went from the highest of highs to thinking how close we were to winning,” he recalled wistfully. “There are always disappointments. You don’t always get what you want.”

“We went from the highest of highs to thinking how close we were to winning,” he recalled wistfully. “There are always disappointments. You don’t always get what you want.”

Through the ups and downs, nearly four decades after first joining them David continues to work with Tennis Canada and its athletes today.

Working with Connell and Tennis Canada and the subsequent success that resulted led to countless other opportunities and requests for David to work with other elite Canadian athletes, teams, and national organizations often simultaneously. The list of Canadian national teams he has worked with over the years is impressive all on its own and includes tennis, basketball, rugby, wrestling, snowboarding, cross-country skiing, wheelchair rugby, skating, softball, wheelchair tennis, curling, and field hockey. You know you’re doing something special when you’re in demand with that many national programs.

“I was asked once what separates David from the other accomplished individuals in his field,” said Celebrini. “My response—he cares deeply. He cares about the athlete, but, more so, about the person.”

For years David taught the sport psychology module for the National Coaching Certification Program. During a single presentation there could be 40-50 coaches in the room representing as many as 20 sports. At various points he also worked with programs such as the 86ers/Whitecaps, the Canucks, the 2001 Mann Cup champion Coquitlam Adanacs, and Simon Fraser University’s athletic program. Former 86er and Whitecaps manager Bob Lenarduzzi, a 1992 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee, noted that David contributed to every team he managed.

“David always impresses with his communication style which is an important element when dealing with a complicated subject such as sports psychology,” said Lenarduzzi. “He communicates in layman’s terms that make it easy for the listener to digest.”

“David always impresses with his communication style which is an important element when dealing with a complicated subject such as sports psychology,” said Lenarduzzi. “He communicates in layman’s terms that make it easy for the listener to digest.”

David’s been a part of Canada’s Olympic team staff at five Olympics working with athletes from various sports. A typical example is the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia. There he worked with the Canadian women’s softball team—which included a young Hayley Wickenheiser—that finished eighth overall, watched Canadian tennis pair Daniel Nestor and Sebastian Lareau win the Olympic gold medal in men’s doubles, and supported the Cinderella run of the underdog Canadian men’s basketball team to a seventh-place finish, something he considers one of the highlights of his career.

“We didn’t have the greatest players, but we had an UNBELIEVABLE team,” he emphasized. “We had a commitment to team dynamics. Jay Triano and Stevie Nash and the boys. It actually changed my way of thinking. I realized that the sum actually can be better than individual parts. There is a reality to something called synergy.”

He continued to work with Nash, a 2016 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee, for many years after throughout his remarkable NBA career.

“I use Steve Nash as an example all the time because he’s a remarkable person, who has a very strong commitment to psychological skills training. I think athletes often appreciate examples: ‘Well, if Nash does this, maybe I should too.’”

Athletes like Connell and Nash weren’t the only ones with whom David forged a strong bond. Another was snowboarder Jasey-Jay Anderson, who was coming off three Olympics with admittedly mediocre results and was feeling the pressure to produce a medal-winning performance at possibly his last opportunity at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. Jasey felt he needed to follow his own individual path. David entered the picture three years before the Vancouver Games and supported Jasey’s position. It gave Jasey the freedom to train and perform in his own way. They worked together for the next three years.

“As the best doctor of sport psychology I have ever had the privilege to work with, David became my greatest ally,” Jasey said.

“As the best doctor of sport psychology I have ever had the privilege to work with, David became my greatest ally,” Jasey said.

At the 2010 Games, Jasey achieved his ultimate goal, winning Olympic gold in the parallel giant slalom. David was there watching in person at the finish line.

“I was down in the circle and we had this embrace at the end of the race that went on for about a minute,” David recalled. “I was totally overwhelmed with emotion and so was he. But once again, I didn’t snowboard down the hill, man! He did. I was just there.”

It’s a point David returns to frequently when recounting the many golden moments achieved by athletes he feels privileged to work with.

“I was fortunate to work with these athletes,” he said. “What they got out of it, well I’m happy. But I was the lucky one. They made me look good.”

Some athletes become such believers in the work David does that they choose to pursue psychology themselves. Take, for example, Canadian wrestling legend Carol Huynh, a 2009 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. Carol worked with David for much of the 2000s while wrestling at SFU, where she also took several of David’s psychology classes.

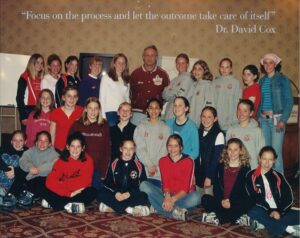

“He was the first person that I ever heard share the concept: ‘it’s the process, not the outcome,’” she said. “This is a line that has stuck with me ever since and has helped me in my athletic career.”

Carol, of course, went on to win Canada’s first-ever Olympic gold medal in women’s wrestling at the 2008 Olympics and added a bronze medal four years later in 2012. She is another who considers David a mentor.

“My success at the Beijing Olympics was in large part to truly buying into the importance of sport psychology,” she said. “Thank you to David for helping me to become an Olympic champion!”

“My success at the Beijing Olympics was in large part to truly buying into the importance of sport psychology,” she said. “Thank you to David for helping me to become an Olympic champion!”

Middle distance running legend Leah Pells, a 2015 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee, is another convert. She first began working with David while running for SFU. A lot of what he said just clicked for her. Leah took David’s introductory sports psychology course and went on to complete her degree in psychology.

“What I quickly noticed was his incredible passion for athletic performance and how it could be maximized using mental training,” she explained. “David observed that athletes who are fixated on an outcome, such as a goal or a win, are often distracted from executing properly. He taught us that by focusing on the process of doing our sport, by being fully present in the moment of the activity, the athlete had a chance to perform at her best, and her best performance gives her a chance to achieve the desired outcome. This philosophy is life changing for an elite athlete. It changed mine.”

Most of Canada bore witness to Leah putting this theory into successful action in the final of the women’s 1500m at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. As Leah prepared for the race of her life she kept coming back to David’s words of wisdom: “Just think of what you are doing in the moment. The outcome will take care of itself.” On the final lap, Leah unleashed an all-out, driving kick to pass three competitors and finish fourth in a personal best time of 4:03.56, just half a second from a bronze medal and to this day the best-ever Olympic finish for a North American woman in the event.

David was watching on TV at his home when his son walked in and asked why there were tears streaming down his face.

“I said, ‘You don’t know what happened! Leah just exceeded her personal best by about seven or eight seconds to finish fourth!’ Every time I watch that I get emotional.”

Leah’s Atlanta performance is a perfect example of what David tries to achieve with every athlete or team that he works with: optimizing their performance for the key moment. At the highest levels of most sports there might only be small differences in technical skill between athletes or teams, perhaps 15% at most. Physical differences are even more minute, often negligible—everyone is in excellent shape. So what is the biggest variance? David believes it is psychological, perhaps as high as 85% difference.

Leah’s Atlanta performance is a perfect example of what David tries to achieve with every athlete or team that he works with: optimizing their performance for the key moment. At the highest levels of most sports there might only be small differences in technical skill between athletes or teams, perhaps 15% at most. Physical differences are even more minute, often negligible—everyone is in excellent shape. So what is the biggest variance? David believes it is psychological, perhaps as high as 85% difference.

“It’s not whether you’ve got the skills,” he explained. “I know lots of people that are great ‘practicers,’ but they’re not great performers. So it’s whether or not you can use the skills in the context that is meaningful, which in sports is performance. The great performers are the ones that can perform under pressure. So you want to help optimize people’s performance in the context of where they are able to perform the skill.”

There are many techniques he uses with an athlete, the sport, or the situation such as imagery, relaxation techniques, or pre-match, match, and post-match preparation. He has lived by a line from the legendary American basketball coach John Wooden: “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.”

“John Wooden also said, ‘I measure my success by preparation.’ If we prepare well, then we’re successful. The competition will play itself out, but if we’ve prepared well, we’ve done the best we can. I focus a lot on that.”

Sometimes all an athlete needs is a key word or reminder and sometimes you have to know when to say nothing at all, as is often the case just before a big game or event.

“You have to read the situation. A lot of times you don’t say anything because it’s too close to competition. But you pick your words well. You know the athlete well and you know what they need. I always say in those situations, don’t try to tell people what they need, ask them what they need. Maybe they ask you to be quiet or if you could get them a coffee. By that point it’s pretty much worked out. I often just try to limit the distractions. You’re protecting them.”

David has been active in his profession long enough now to bear witness to striking changes today in sport psychology compared to his early days.

David has been active in his profession long enough now to bear witness to striking changes today in sport psychology compared to his early days.

“Way more acceptance. At some level, it’s still sport specific. It’s not across the board. Some sports are really invested in sports psychology. But some sports less. Some sports still don’t see a role for psychologists in the same way other sports do. But the acceptance level is high, plus we’re way better at doing what we do. I think we’re also much better at recognizing there are serious psychological issues in sport that affect people. Often things happening in an athlete’s life outside of sport that affect their performance.”

On top of everything else on his plate David has also found the time to serve as the Chair of SportMed BC for 22 years, although he has been involved with the organization essentially since its inception in the early 1980’s.

And he has no plans of stopping any time soon. His passion for sport, sport psychology, and working with athletes hasn’t waned over the years. If anything, it has increased.

“People sometimes say, ‘Why don’t you retire?’ I say, ‘What would I do? Go to Summerland and mow the lawn?!’ I’m privileged. I’m going to walk into the Whitecaps locker room this week to give a talk to the boys and my heart is going to pound. This is fantastic. I’m so fortunate.”

Induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame certainly isn’t the end, but it is something that David is immensely proud of, not only personally, but also for what it means for the larger field of sport psychology.

“I can’t describe it. When I first heard I was being inducted into the Hall, I was overwhelmed emotionally. I’ll tell you, these last two years teaching through Covid have been the most stressful of my academic life. When I’m not feeling on top of it, I think: ‘I’m going into the Hall of Fame, man!’ And I say to my kids, ‘I’m going to be in the Hall of Fame and you’ll be able to go push a button and I’ll be there when I’m not here anymore.’ That’s pretty cool. It means a lot to me, but it also means a lot to my profession in sports science. This is sort of…I wouldn’t say vindication, but in support of everything I believe in. You made a difference. It’s acceptance. It’s huge for me and for my profession.”

As part of the Class of 2021, David Cox will be formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Builder category at the annual Induction Gala to be held June 9, 2022 at the Vancouver Convention Centre.