Doug Hepburn: Strongest Man in the World

August 31, 2022By Jason Beck

Last week as we marked 69 years since Doug Hepburn’s 1953 world heavyweight weightlifting championship, it occurred to me that next year will mark seven decades since his historic and unlikely world title. That blew me away because the same month that I started working at the BC Sports Hall of Fame the 2003 World Weightlifting Championships were held in Vancouver to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Hepburn’s historic win, still to this day the only Canadian man to win the world heavyweight weightlifting crown and earn the title of ‘world’s strongest man.’ Time really does fly.

seven decades since his historic and unlikely world title. That blew me away because the same month that I started working at the BC Sports Hall of Fame the 2003 World Weightlifting Championships were held in Vancouver to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Hepburn’s historic win, still to this day the only Canadian man to win the world heavyweight weightlifting crown and earn the title of ‘world’s strongest man.’ Time really does fly.

I believe the first article I wrote for the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s 4 The Record newsletter—back when newsletters were still printed on paper—was on Doug Hepburn shortly after my time with the Hall began. His gold medal victory at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games became a key story in my first book The Miracle Mile.

So although I never had the opportunity to meet Doug, I’ve always had a bit of a soft spot for his unlikely, underdog story.

And I’m not alone in that way.

Maybe more than any other athlete inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame, over the years countless visitors to the Hall like to share how they knew Doug or saw him demonstrate one of his remarkable feats of strength like ripping license plates apart with his bare hands or lifting the Trout Lake lifeguard boat onto his back unassisted. Many purchased fitness equipment or training programs from him from his Vancouver warehouse over the years. A few got to know him well and were amazed at his varied talents far beyond lifting unliftable steel weights.

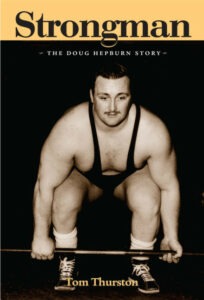

For decades after his 1953 world championship, Hepburn lived the remainder of his life in Vancouver and was something of a cult legend. But few knew the full story of how Hepburn won the 1953 world title and also how unappreciated he was in his own hometown. I certainly didn’t until reading Tom Thurston’s excellent 2003 book Strongman: The Doug Hepburn Story. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend it. But for our purposes here, let’s look back in detail at Doug’s 1953 world title. It’s one of the great underdog stories in BC sport history.

For decades after his 1953 world championship, Hepburn lived the remainder of his life in Vancouver and was something of a cult legend. But few knew the full story of how Hepburn won the 1953 world title and also how unappreciated he was in his own hometown. I certainly didn’t until reading Tom Thurston’s excellent 2003 book Strongman: The Doug Hepburn Story. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend it. But for our purposes here, let’s look back in detail at Doug’s 1953 world title. It’s one of the great underdog stories in BC sport history.

First, some background. A team of the best scriptwriters in Hollywood couldn’t have come up with a story like Doug Hepburn’s. They didn’t break the mold with him; his story was so larger-than-life it wouldn’t have fit to begin with. By 1953, Hepburn had already survived serious physical disabilities, numerous operations to correct them, a broken home, poverty, the ridicule of his schoolmates, loneliness, depression, and the apathy of his hometown and country for his early lifting accomplishments. In spite of it all and without any coaching, he had turned himself into the strongest man in the world. It’s just that no one knew it yet.

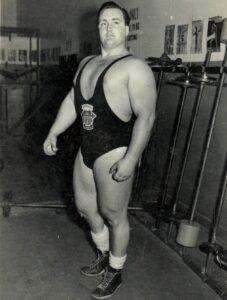

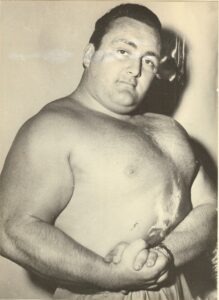

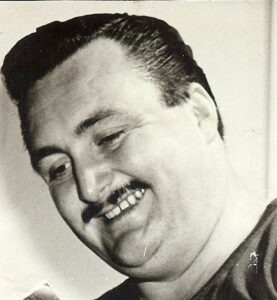

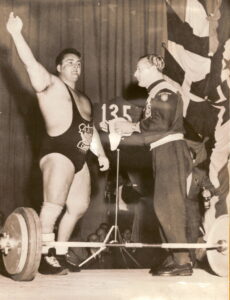

In many ways, Hepburn was a throwback to the days of the traveling circus strongman. He looked the part with more muscle mass than definition, neatly coiffed hair, and often sporting a finely trimmed moustache. Only 5 ft 8½ in in height but weighing over 300 lbs at his peak, Hepburn was solid as a rock. The first thing you noticed were his massive shoulders. Seemingly hewn from chunks of telephone poles, Hepburn possessed perhaps the strongest shoulders in history to that point in time. He often said he felt he could lift any weight above his head if he could bring it to chest height; regardless of the burden, his shoulders would take care of the rest from there.

Bob Hoffman, the founder of York Barbell in Pennsylvania, once confided to Hepburn, “You realize you don’t have the organs of a normal man.”

There was a lot of truth to that statement.

Hepburn’s biceps were larger than the average man’s thighs, measuring about 24 inches at their peak. His fists resembled meaty rotary telephones. A wristwatch that fit any other man’s forearm loosely looked cartoonishly small on his. A reporter once quipped that gripping his hand was “like trying to wrap your fingers around the hind ankle of an elephant.” His thighs resembled two bulging tree trunks above the knees. Below them on the right was his withered clubfoot, making his upper thighs appear even larger and the strength they possessed all the more remarkable. Above a thick neck was a cherubic face: dark eyes, sharp nose, all framed  by oily black hair slicked back and parted. His smile seemed sad at the corners.

by oily black hair slicked back and parted. His smile seemed sad at the corners.

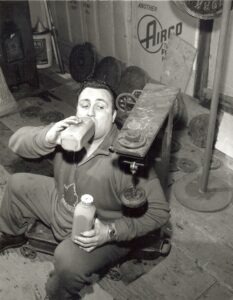

Even his appetite was impressive. The average active 25-year-old male’s daily food intake amounts to approximately 3000 calories; Hepburn was inhaling over 8000 at this time.

“I ate three times a day and three times a day I had to fight to keep from throwing up,” he told The Province in 1967. “A couple of times I did. One day I gained seven pounds.”

When his appetite was at its glutinous peak, his daily food intake looked something like this:

“Breakfast

- Quart of whole milk.

- Large steak.

- Six boiled eggs.

- Five thick pieces of buttered toast.

- Four more glasses of milk.

- Bowl of soup.

- Two bowls of pudding.

Mid-Morning Snack

- Four quarts of whole milk.

- Six bananas.

- Six oranges or peaches.

- Six tins tomato juice.

Lunch

Fish and chips (or another steak) with all the trimmings.

Mid-Afternoon Snack

More milk and fruit.

Dinner

- Another steak or two large tins of spaghetti.

Bedtime Snack

- Two large hamburgers and more milk.”

When he wasn’t eating, Hepburn all but lived in the gym lifting weights. Most elite lifters then were training using what was known as the “5×8 method”: lifting medium weights a maximum of eight reps per set with five sets per exercise. Through trial and error, Hepburn devised a more effective 10×3 method with the simple premise of lifting much heavier weights a maximum of three reps per set over ten sets rather than five. This new system gave Hepburn a more powerful “pump” drawing more blood to the muscles he was focusing on and promoting increased muscle growth. A second discovery took this principle even further. Hepburn devised a program that involved lifting the heaviest weights possible for a single repetition, while performing these “heavy singles” eight to ten times. These simple variations on common techniques afforded Hepburn massive gains in size and strength and later influenced future generations of lifters all over the world. It is why many strength aficionados today still cite Hepburn as one of the “grandfathers” of modern powerlifting training techniques.

lifting medium weights a maximum of eight reps per set with five sets per exercise. Through trial and error, Hepburn devised a more effective 10×3 method with the simple premise of lifting much heavier weights a maximum of three reps per set over ten sets rather than five. This new system gave Hepburn a more powerful “pump” drawing more blood to the muscles he was focusing on and promoting increased muscle growth. A second discovery took this principle even further. Hepburn devised a program that involved lifting the heaviest weights possible for a single repetition, while performing these “heavy singles” eight to ten times. These simple variations on common techniques afforded Hepburn massive gains in size and strength and later influenced future generations of lifters all over the world. It is why many strength aficionados today still cite Hepburn as one of the “grandfathers” of modern powerlifting training techniques.

If Hepburn had been a weightlifter in the Soviet Union or other eastern European countries at that time, he would have been a national hero. In BC in the 1950s, he was considered an oddball curiosity. In eastern Canada, officials refused to even believe someone in the west could be this strong.

At a March 1949 BC Weightlifting Association-sanctioned meet in Vancouver, Hepburn set a Canadian clean-and-press record of 300 lbs. Eastern officials refused to accept the record on the grounds that it was too good. Record forms sent to the CAAU in the east were returned to the West Coast with a note: “Impossible. This man could not possibly have lifted 300 lbs. Why, the best in the east does only 220. You have made a mistake.”

Eventually the east grudgingly began to accept his record-breaking lifts, but Hepburn was still somehow passed over for selection to the 1952 Canadian Olympic team competing in Helsinki. Shortly after the Olympics took place, in protest Hepburn gave a lifting demonstration at Vancouver’s Kitsilano Pool. He set an unofficial world record in the clean-and-press of 353½ lbs, an unofficial Canadian snatch record of 269 lbs, and an unofficial Canadian clean-and-jerk record of 384½ lbs. Eastern officials refused to accept the records because they were performed on a Sunday. His three-lift total would have earned him a silver medal at the Olympics had he been chosen to go. Two months after the Olympics, Hepburn unofficially broke world records in all three Olympic lifts—two held by Olympic champion John Davis of the USA and one by Hepburn himself—and would have topped Davis’ gold medal total by 26 lbs.

Eventually the east grudgingly began to accept his record-breaking lifts, but Hepburn was still somehow passed over for selection to the 1952 Canadian Olympic team competing in Helsinki. Shortly after the Olympics took place, in protest Hepburn gave a lifting demonstration at Vancouver’s Kitsilano Pool. He set an unofficial world record in the clean-and-press of 353½ lbs, an unofficial Canadian snatch record of 269 lbs, and an unofficial Canadian clean-and-jerk record of 384½ lbs. Eastern officials refused to accept the records because they were performed on a Sunday. His three-lift total would have earned him a silver medal at the Olympics had he been chosen to go. Two months after the Olympics, Hepburn unofficially broke world records in all three Olympic lifts—two held by Olympic champion John Davis of the USA and one by Hepburn himself—and would have topped Davis’ gold medal total by 26 lbs.

Hepburn used all of this rejection as fuel and shifted his focus to the 1953 World Championships in Stockholm, Sweden. The CAAU chose not to send any athletes to the worlds that year, so Hepburn needed to raise funds to get there on his own. Today it seems hard to fathom a world record holder in any sport—even in the poorest of nations—not receiving any financial assistance from sporting bodies to represent his or her nation on the world stage. Hepburn may have been among the strongest men on earth, but he would be forced to pass the hat just to prove that fact overseas.

Lifting exhibitions including during Vancouver Mounties baseball games were organized with the proceeds going towards Hepburn’s $1377 plane ticket to Sweden. Just weeks before the world championships, the money was raised and Hepburn was packing his bags.

“I was elated!” he recalled. “I was about to fulfill my lifelong dream, and determination alone had been the key.”

In his excited state after learning the news, Hepburn raced home and still in his street shoes heaved a 290 lb barbell over his head in euphoric delight. The celebration was short-lived, as his street shoes lost their grip and he tumbled to the ground still gripping the barbell. He had sprained his fused right ankle so severely that it could barely sustain his body weight. Once the rage over his own carelessness had subsided, Hepburn resolved himself to a recovery effort involving plenty of rest, massage, muscle and ligament supplements, and a dedicated program of visualization.

“Over and over I imagined…myself fully recovered and setting a new world record in each of the three competition lifts…until I could actually feel the lifts go up and hear the crowd roar as I held the winning poundages above my head: no pain, no weakness, no fear of failing! I would win and I would not entertain any thoughts to the contrary!”

After a long flight in which his wide frame took up two seats, he arrived in Stockholm and went straight to the Erikdalhallen Arena. His entrance proved how well known his abilities had become outside of Canada. The crowd hushed as he strolled in with a slight limp, duffel bag over his shoulder. Officials and athletes were momentarily diverted from the competition turning their heads to see who had arrived. A lone voice whispered just loud enough for Hepburn to hear, “He’s here.” As Hepburn scanned the hundreds of curious faces focused on him, he could only think to himself: ‘This is where my fate will be decided.’

That night, Hepburn found that while massaging his sore ankle it wasn’t nearly as swollen and painful as it had been days earlier. He laid on his bunk, eyes closed, and visualized himself winning: “hearing the cheers of the crowd as I completed the gold medal lift; feeling the rush of my adrenalin as I was handed my gold medal and pronounced ‘World’s Strongest Man’—clear and undeniable proof before the entire world.”

At the arena the next morning, Hepburn quietly remained focused, taking in the other weight class competitions before warming up for his own. This was the moment he had worked day after day for years to reach. It was a strange feeling he described later:

At the arena the next morning, Hepburn quietly remained focused, taking in the other weight class competitions before warming up for his own. This was the moment he had worked day after day for years to reach. It was a strange feeling he described later:

“I am not familiar with Pavlov, but I do know that…if a man lives with auto-suggestion in his subconscious mind and he told himself that in five years he is going to break a world record and he lives with it night and day, do you realize that when that point comes how that man is wound up, if he believes it. He literally will reach a stage, which I have felt, which is beyond comprehension. You literally explode.”

His ankle was still sore, but he was determined to lift. The British team coach, Al Murray, noticed he was hiding a limp and inquired about it.

“I’ll lift,” Hepburn answered firmly. “I can’t win unless I do. And I fully intend to win!”

Murray, without a British lifter in Hepburn’s class, seemed impressed with the resolve of the strong-willed Canadian. He offered to help Hepburn prepare a strategy for beating the Olympic champion John Davis, noting, “I know Davis’s lifting capabilities better than he does.” Lacking a coach or an advisor of any sort at this competition, Hepburn gladly accepted.

The heavyweight competition had a deep field and would prove crucial to deciding the overall team standings. Hepburn found himself at the center of a Cold War tug-of-war. The Americans saw him as a threat to Davis’s crown and an obstacle to winning the team title, a title they’d never failed to capture thus far in the championship’s history. Following coach Bob Hoffman’s lead, they took every opportunity to glare wordlessly in Hepburn’s direction, treating their Canadian neighbour coldly throughout the competition. The Russians were friendlier, partially because there were no Soviet lifters in the heavyweight class and partially because if Hepburn finished ahead of the American lifters, the Russians would take the team title. The Russian team doctor, a short man named Eganyan, offered Hepburn a full physical before the competition and declared him fit to lift with a friendly pat and smile: “Velikolepno!” or “Magnificent!”

Cold War tug-of-war. The Americans saw him as a threat to Davis’s crown and an obstacle to winning the team title, a title they’d never failed to capture thus far in the championship’s history. Following coach Bob Hoffman’s lead, they took every opportunity to glare wordlessly in Hepburn’s direction, treating their Canadian neighbour coldly throughout the competition. The Russians were friendlier, partially because there were no Soviet lifters in the heavyweight class and partially because if Hepburn finished ahead of the American lifters, the Russians would take the team title. The Russian team doctor, a short man named Eganyan, offered Hepburn a full physical before the competition and declared him fit to lift with a friendly pat and smile: “Velikolepno!” or “Magnificent!”

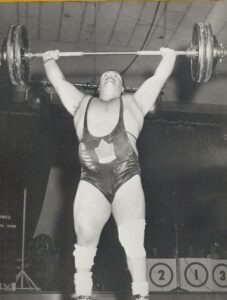

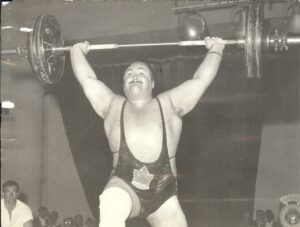

Ultimately, the heavyweight class came down to three men who distanced themselves from the rest of the field—Hepburn, Davis, and the colorful Humberto Selvetti from Argentina. First up was Hepburn’s signature lift, the clean-and-press—the perfect way to quickly build some confidence in his sore ankle and hopefully put some cushion between himself and the rest of the field.

Davis finished with a best lift of 341½ lbs, while Selvetti grunted out a 352½ lb performance. Selvetti celebrated each successful lift with a kiss on his coach’s cheek as he stepped down from the platform. When Hepburn matched his 352½ lb lift, Selvetti happily kissed Hepburn. Hepburn made crystal clear to anyone watching which man possessed the strongest shoulders on the planet finishing with a 369¼ lb heave for a new world record in the clean-and-press. After Hepburn bettered the Argentine’s total, the smile left Selvetti’s face and he didn’t kiss Hepburn this time, a fact Hepburn laughed about in later years. Hepburn’s technique had always appeared smooth and effortless, so upon seeing how easily the Canadian raised the straining steel barbell above his head was a serious psychological blow to both Davis and Selvetti. They were in a deep hole already and knew it.

Next came the snatch, Hepburn’s most challenging lift at the best of times, owing to the limited range of motion of his fused ankle, but one he currently feared performing with an injury to the same ankle on top of that.

“Just match the beggars,” Murray instructed him. “Match them and your superior pressing power will keep you well ahead.”

“Just match the beggars,” Murray instructed him. “Match them and your superior pressing power will keep you well ahead.”

Selvetti managed a best snatch of 275½ lbs, while Davis snatched 297½ lbs, leaving Hepburn with some significant work to do. After a successful lift of 275½ lbs, Hepburn’s ankle grew so painful he couldn’t hide it any longer. Eganyan, the Russian doctor, noticed immediately and produced a vial that he forced Hepburn to sniff. The strongman perked right up and forgot about the pain in his foot. Although Hepburn was competing in the tail end of when international weightlifting could be characterized as relatively “drug-free” compared to more recent decades when steroids, wraps and weight belts have all contributed to making the sport a shadow of what it once was, there were a few superficial drugs used by lifters to gain an edge. This substance offered to Hepburn in the vial—likely some sort of stimulant—was such an example, but its effectiveness in providing any edge short of a brief spell of heightened alertness can be questioned.

“I’d say the power of suggestion likely had a lot to do with it,” a skeptical Toronto doctor said.

“It smelled like ammonia but was a lot stronger,” admitted Hepburn.

Even still, it didn’t help him immediately as he failed to complete his first attempt at 297½ lbs to match Davis’s total.

When Hepburn attempted 297½ lbs a second time, in a disrespectful move to salvage the overall team title, the American contingent, including Hoffman, did their best to distract Hepburn while in the midst of his lift and also convince the judges that he had faulted by touching a knee to the ground. Neither the crowd nor the judges fell for the classless ruse—the crowd booing the Americans heavily, while the judges signaling the lift was clean. With just the clean-and-jerk left, Hepburn was in a commanding position, but remained focused.

Murray slapped Hepburn on the back and yelled, “You’ve done it, Doug! He’s bloody kippered!”

“Not yet,” Hepburn insisted, doing his utmost to stay relaxed.

“Yes he is!” Murray countered. “Davis would have to jerk 392 lbs to beat you and no bloody way can he today!”

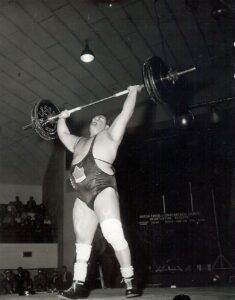

Murray’s word proved prophetic—but only just. Selvetti managed a 363¾ lb clean-and-jerk to finish with a three-lift total of 991¾ lbs. Davis succeeded at 369¼ lbs on his first lift, moved up to 391¼ lbs to try and tie Hepburn, but failed on both attempts to finish with a three-lift total of 1008¼ lbs. Hepburn started at 341½ lbs and was good, moved to 363¼ lbs and missed, his knee just touching the floor.

It now came down to his final attempt to ensure victory. If successful, he would finish with a winning total of 1030 lbs. If he failed, he would finish tied with Davis at 1008¼ lbs, but Davis would be awarded the gold because he had a lower body weight.

The strain of the competition thus far had Hepburn feeling slightly fatigued and, worse, his ankle was now screaming pain. He couldn’t hide it any longer. Eganyan produced the mystery vial once more, making Hepburn lie down and relax while he sniffed the contents.

Feeling slightly revived, Hepburn approached the bar cautiously. This was it. Bending over to grip the bar, he simultaneously exploded upwards from the thighs and shoulders and everything went black. To his dying day, he maintained he had no recollection of raising this most significant of lifts. He regained consciousness to find himself in the perfect technical position—a position he had never yet been able to reach in seven years of training and competing—the bar at his chest and his knee a scant half inch from grazing the platform. Hoffman and the other Americans were again down on their hands and knees seemingly trying to will that knee to touch. The width of the average person’s index finger—this is all that separated victory from defeat for Hepburn.

Feeling slightly revived, Hepburn approached the bar cautiously. This was it. Bending over to grip the bar, he simultaneously exploded upwards from the thighs and shoulders and everything went black. To his dying day, he maintained he had no recollection of raising this most significant of lifts. He regained consciousness to find himself in the perfect technical position—a position he had never yet been able to reach in seven years of training and competing—the bar at his chest and his knee a scant half inch from grazing the platform. Hoffman and the other Americans were again down on their hands and knees seemingly trying to will that knee to touch. The width of the average person’s index finger—this is all that separated victory from defeat for Hepburn.

With the bar at his chest, a curious thing occurred. The captivated crowd of over 5000 began roaring its applause. Hepburn hadn’t even completed the lift and they already knew. He had done it. He raised the bar over his massive shoulders and then above his head, locking in his elbows and holding it firm for an extra second or two just for insurance. The ovation rocked the building. As the judges scored the lift ‘good,’ he allowed the barbell to fall to the floor.

At that moment, it wasn’t the only weight lifted off his shoulders. A sense of relief washed over him as the burden of years of trial and toil momentarily fell away. It was done. A scrawny, shy weakling with crossed eyes and a clubfoot had built himself into the strongest human on the planet. If the name Hepburn had registered with few before, now it would echo off the lips of millions with a sharp steel clang. With the barbell lying at his feet, a Swedish attendant ran up to him to offer first congratulations. Hepburn flashed a broad smile—the first he’d shown in days—towards the cheering throng and raised a thick arm in a long wave of acknowledgment. All those other moments of despair and frustration had been worth it for this one, the memory of which would outlive them all.

Hepburn was suddenly the toast of the strength and bodybuilding world. The Swedes did their utmost to make him feel like a celebrity—which he now was as a result—tacking his photograph to telephone poles all over the country. Word of Hepburn’s championship filtered back to Vancouver and created a sizable buzz, finally resulting in the attention he so craved and deserved.

The Vancouver Sun, no longer able to pass off Hepburn’s happenings as afterthought or token curiosity piece, ran a front-page article that announced his victory and a second story inside with a headline of “Hepburn’s Mighty Heart Earns Plaudits of World.” The piece took on a slightly apologetic tone acknowledging the neglect the city had dealt Hepburn in previous years: “All Vancouver can do is humbly welcome home a great champion and take pride in the fact this is his home.” Two days later, the Sun ran an editorial entitled “Mighty Spirit Wins” that further lauded Hepburn’s feat:

“The magnificent muscles which hoisted Vancouver’s Doug Hepburn to world champion weightlifter are not nearly so impressive as the spirit which built them.

Ten years ago he weighed only 145 lbs. Thoughtless schoolmates sneered at the clubfoot and shriveled right leg nature had inflicted on him. Today he’s 280 lbs and can lift more than any man in the world…

Now Doug Hepburn sits on top of the world.

Mightier however than his body is his indomitable spirit.

He’s a lesson to all of us in what self-confidence and unflagging determination can do.”

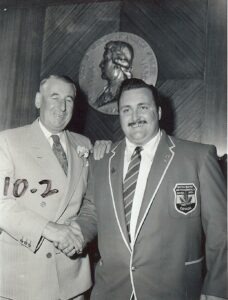

Upon Hepburn’s return to Vancouver he was met at the airport by Mayor Fred Hume and a handful of other prominent amateur officials. Then with a police escort Hume toured Hepburn around the city in his limo waving to residents. For Vancouver’s first world champion in any sport since boxer Jimmy McLarnin and sprinter Percy Williams over twenty years earlier, there probably should have been a larger celebration marking Hepburn’s triumphant return.

But eventually more recognition would come from City Hall in the form of a Civic Merit Award. It wouldn’t stop there either. By early 1954, Hepburn had been named the winner of The Province’s Hector McDonald Memorial Award as BC’s athlete of the year, the Vancouver Sun’s inaugural Athlete of the Year, the Canadian Press’s top Canadian athlete of 1953, the CAAU’s outstanding amateur athlete, induction into the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame, and the Lou Marsh Award as Canada’s Outstanding Athlete. In 1966, he was included in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s inaugural induction class.

But eventually more recognition would come from City Hall in the form of a Civic Merit Award. It wouldn’t stop there either. By early 1954, Hepburn had been named the winner of The Province’s Hector McDonald Memorial Award as BC’s athlete of the year, the Vancouver Sun’s inaugural Athlete of the Year, the Canadian Press’s top Canadian athlete of 1953, the CAAU’s outstanding amateur athlete, induction into the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame, and the Lou Marsh Award as Canada’s Outstanding Athlete. In 1966, he was included in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s inaugural induction class.

After his world championship victory, Hepburn’s life was one of many extreme ups and downs, but weightlifting remained at his core and he continued to set world masters records into his seventies before his death in November 2000.

Sadly, many remain unaware that BC was once home to the world’s strongest man. Recently though a group has been working to remedy that. A fundraising effort to complete a bronze statue to commemorate Doug Hepburn and his remarkable weightlifting career is now underway. Sculptor Norm Williams, who created the Roger Neilson and Pat Quinn statues at Rogers Arena, has already begun work on his latest masterpiece. If you’d like to support the effort to honour Doug Hepburn, please visit: https://www.gofundme.com/f/the-doug-hepburn-statue-project