Robin Bawa: From the Pond to the Big League – 2020 Inductee Spotlight

February 29, 2020By Jason Beck

As ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ echoed in Washington’s Capital Center, Robin Bawa stood at the blue line shifting his weight over his skates side-to-side, slightly nervous, but focused on what was to come. It was October 6, 1989, the Washington Capitals’ home opener versus the Philadelphia Flyers. After winning the Patrick Division the previous season, as part of the pre-game ceremony the Capitals raised a division title banner to the rafters. It was a momentous occasion, but for a different reason few realized at that moment.

As ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ echoed in Washington’s Capital Center, Robin Bawa stood at the blue line shifting his weight over his skates side-to-side, slightly nervous, but focused on what was to come. It was October 6, 1989, the Washington Capitals’ home opener versus the Philadelphia Flyers. After winning the Patrick Division the previous season, as part of the pre-game ceremony the Capitals raised a division title banner to the rafters. It was a momentous occasion, but for a different reason few realized at that moment.

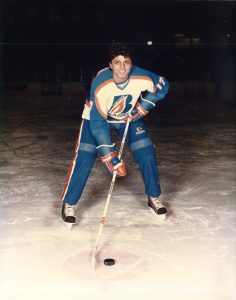

Robin, a twenty-three-year-old rookie from Duncan, 45 km north of Victoria on Vancouver Island, was making his NHL debut that night. He’d made it to the Big League. More significantly, as the puck was dropped at center ice, Robin became the first player of South Asian descent to play not only in the NHL, but is believed to be the first athlete of South Asian heritage to suit up in one of North America’s four major professional sports leagues: the NFL, MLB, NBA, and NHL.

His family back home in Duncan watched the game proudly on satellite TV. If only his grandfather Bawa Singh could have been there to witness this moment. No doubt he’d have been proud of his grandson. It was 83 years earlier in 1906 that the Bawa family patriarch for which they are named had immigrated to Canada, one of the first to come from India. He settled in Paldi, a small village 15 minutes from Duncan where a community of Sikh Canadians and other ethnic groups lived in relative harmony, away from the larger communities where you’d still find barber shops with ‘Whites Only’ signs in the windows.

“My grandpa is the real pioneer,” Robin says. “He came over with nothing when there was nothing here.”

His grandmother came to Canada from India a few years later. She and Bawa married despite never seeing one another in person. They raised five boys. Bawa worked in the lumber mills every day to support his family, eventually earning enough to buy some acreage and a small farm. Who could have guessed that one day from these hardscrabble beginnings his grandson would play in the world’s best hockey league?

Even Robin didn’t fully grasp his remarkable pioneering accomplishment then. “At the time you don’t realize that,” he recalled recently. “You’re just working so hard and you’re in the moment. You don’t have time to enjoy it. I was just focused.”

That trained focus led to an immediate impact. On his opening shift, the puck came to towering Flyers defenseman Kjell Samuelsson and it might as well have been a train that ran the 6’6” 230 lb. defenseman over. Robin crunched Samuelsson with a clean open-ice hit that brought a roar from the Capitals faithful. “That was probably one of the best hits of my career,” chuckled Robin. “I just nailed him.”

That trained focus led to an immediate impact. On his opening shift, the puck came to towering Flyers defenseman Kjell Samuelsson and it might as well have been a train that ran the 6’6” 230 lb. defenseman over. Robin crunched Samuelsson with a clean open-ice hit that brought a roar from the Capitals faithful. “That was probably one of the best hits of my career,” chuckled Robin. “I just nailed him.”

After the big hit the Flyers suddenly wanted a piece of the confident rookie. Flyers tough guy Craig Berube, currently coach of the Stanley Cup champion St Louis Blues and Robin’s former roommate from back in their Western Hockey League days, tried to take a run at Robin in retaliation, but Capitals granite-hard defenseman Scott Stevens came to his rescue. Robin’s early hit set the tone as Washington went on to win 5-3.

In his second NHL game the very next night versus the Chicago Blackhawks, Robin made an even stronger impression.

“I had a pretty good game actually,” he remembered. “Bob Rouse passed me the puck—I was on my off-wing—and it bounced behind me. I took it off the boards, went in on a breakaway and scored. First NHL goal, second game.” Blackhawks goaltender Alain Chevrier never had a chance as Robin’s low shot ripped in off the far post. Hawks coach ‘Iron’ Mike Keenan clearly noticed Bawa’s strong on-ice play, at one point yelling, “We got someone for you Bawa!”

Battling for scraps of ice time on a very good Washington team that featured the likes of Dale Hunter, Mike Gartner, and fellow Vancouver Island boy Geoff Courtnall and feeling stuck in the minors, Bawa requested a trade and in 1991 was sent to his home province team, the Vancouver Canucks. Making his Canucks debut in front of dozens of family and friends in the Pacific Coliseum seats, Robin ‘certainly made a splash,’ as Canucks play-by-play broadcaster Jim Robson exclaimed excitedly on-air when he smashed through the arena glass in the Hartford Whalers zone while attempting to check Kevin Dineen into the boards. The crowd went wild, buzzing at the rare sight and wondering who this young BC boy was. Maybe Brian Burke, then Canucks director of hockey operations put it best:

“He’s got good hands, he can score, he can skate and he’s belligerent. And he can fight. His folks did a nice job bringing him up. He’s a polite, hard-working, young man with good values and it’s a real pleasure for me to see him get a shot [at the NHL].”

Shuttling back and forth between the NHL and the IHL over 12 professional seasons, Robin later went on to play with the San Jose Sharks and Mighty Ducks of Anaheim in the NHL scoring six goals over 61 career NHL games. Upon retirement due to a series of concussions in 1999, Robin had accumulated 180 goals, 221 assists, and 401 points in 724 career minor league games. He was honoured with induction into the North Cowichan Sports Wall of Fame in 2012 and the BC Hockey Hall of Fame in 2016.

Shuttling back and forth between the NHL and the IHL over 12 professional seasons, Robin later went on to play with the San Jose Sharks and Mighty Ducks of Anaheim in the NHL scoring six goals over 61 career NHL games. Upon retirement due to a series of concussions in 1999, Robin had accumulated 180 goals, 221 assists, and 401 points in 724 career minor league games. He was honoured with induction into the North Cowichan Sports Wall of Fame in 2012 and the BC Hockey Hall of Fame in 2016.

This already is a remarkable athletic tale, but the most extraordinary part of Robin’s story is his unlikely rise to that first NHL game in 1989 with the Capitals and the obstacles he overcame to get there. Few NHLers have faced longer odds and more blatant racial discrimination.

Born and raised in Duncan, as a young boy Robin had asthma and as a remedy the doctor suggested his parents put him in sports. He began playing soccer at age six and soon was playing anything he could, a natural all-round athlete.

Born and raised in Duncan, as a young boy Robin had asthma and as a remedy the doctor suggested his parents put him in sports. He began playing soccer at age six and soon was playing anything he could, a natural all-round athlete.

Sitting down for an interview at the BC Sports Hall of Fame in late January, Robin’s description of his introduction to hockey shook me to my core. After hundreds of interviews with athletes of varied backgrounds, many parallels and patterns can be seen, but Robin’s experience was different and his raw emotion hit home.

“It was funny because there was a bunch of kids that played hockey in my school,” he began. “I’m not sure how it went, but I said to them, ‘I want to play.’ They said, ‘Well, your kind doesn’t play.’”

He paused, getting choked up at the memory of this, his eyes glassy with tears. Seeing a battle-hardened middle-aged NHLer who’d faced some of the toughest men in hockey still affected by the pain of this moment almost 50 years later should get to every Canadian.

“I don’t think it was meant as any ill will when the kids said that,” Robin later explained. “I think they didn’t know any better because they didn’t see any minorities play hockey. It was mostly a Caucasian sport, a white man’s sport then, right? As you’re in it, you don’t understand it. When it happens, it was so innocent.”

For a lot of new Canadian boys and girls, that’s where this story often ends. What happened next changed the course of Robin’s life and that of hockey in general. He went and told his dad what happened.

“I asked him, ‘Hey Dad, can I play hockey?’

‘Sure why not?’”

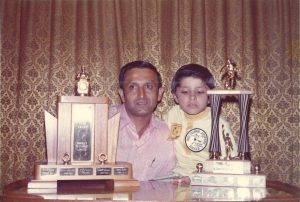

By coincidence that same week, Robin’s dad, Sirjeet ‘Sarge’ Bawa, a hard-working truck driver and mechanic, had been invited by a coworker to bring his boys out to a nearby pond in Duncan that froze over and play some shinny. So Sarge and Robin went out and bought a pair of skates.

By coincidence that same week, Robin’s dad, Sirjeet ‘Sarge’ Bawa, a hard-working truck driver and mechanic, had been invited by a coworker to bring his boys out to a nearby pond in Duncan that froze over and play some shinny. So Sarge and Robin went out and bought a pair of skates.

“So I got my new skates on, went out there, couldn’t stand up, fell down, couldn’t stand up, fell down,” remembered Robin, his face lighting up at the memory. “My cousins were out there too. By the end of the day, we were moving not bad. Going around pretty good. Yeah, it was fun. That was the first time. So then I liked it.”

So much so that every day after Sarge got home from another long 12-hour workday that began before dawn, he’d take Robin down to the pond whenever it froze to learn how to skate.

“My Dad didn’t skate. He’d have shoes on. He didn’t want me to go too far and fall in the water. First day it was trying to skate from me to you. Then a few feet farther. So every day, that’s how I learned. It was awesome. I wish people could experience skating on a frozen pond more often. Those were the days. That’s what made it so fun.”

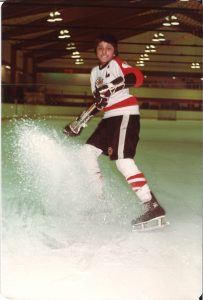

From there Robin began playing minor hockey and slowly improving as he worked his way up the age levels. By age 12, he was playing for the Fuller Lake Flyers under coach Jack Rochon alongside close buddy and fellow future NHLer Doug Bodger. Sarge drove the team to games in their own bus painted in Philadelphia Flyers orange, white, and black.

From there Robin began playing minor hockey and slowly improving as he worked his way up the age levels. By age 12, he was playing for the Fuller Lake Flyers under coach Jack Rochon alongside close buddy and fellow future NHLer Doug Bodger. Sarge drove the team to games in their own bus painted in Philadelphia Flyers orange, white, and black.

Admittedly, the NHL wasn’t even on Robin’s radar then. He watched Hockey Night in Canada every Saturday and loved the Bruins, especially Bobby Orr and Rick Middleton, but in his mind the NHL might as well have been a million miles away from Duncan.

“I knew of the NHL, but didn’t know the NHL—you know what I mean? I thought Doug’s older brother Don Bodger playing Junior B was the cat’s meow. I thought Junior B was where it was at. It wasn’t until I was 14 or 15 that I realized maybe I want to pursue hockey and see how far I can go.”

It was at that age that Robin and Doug were claimed by the New Westminster Bruins of the Western Hockey League. They began their junior career with the Kamloops Jr. Oilers after the Bruins relocated to the Interior. Robin was a pure goal scorer in junior and fit in well in Kamloops, arriving at the beginning of the Kamloops dynasty that included WHL titles, Memorial Cups, and dozens of alumni who went on to NHL careers.

In Robin’s first year, Kamloops made it to the WHL playoffs and recorded a 55-point improvement from the previous season. In his second, they won the WHL title and finished third at the Memorial Cup in Laval, Quebec. It was at this age that the development of others like friend Doug accelerated (Bodger was a 9th overall draft pick of Pittsburgh in 1984), whereas his own plateaued. A skilled, natural scorer, some of his coaches tried to get him to play a tougher, meaner game, “but I didn’t have it in me at the time.”

Robin not only went undrafted, but was traded to Moose Jaw in his third year of junior. He considered quitting and going back to school, but was traded to New Westminster where he played for three months and was a frequent recipient of racially-charged verbal abuse from his own home fans. Kamloops traded back for him though and he returned to the newly re-named Blazers. Ken Hitchcock was coaching by then and was a major influence on Robin.

Robin not only went undrafted, but was traded to Moose Jaw in his third year of junior. He considered quitting and going back to school, but was traded to New Westminster where he played for three months and was a frequent recipient of racially-charged verbal abuse from his own home fans. Kamloops traded back for him though and he returned to the newly re-named Blazers. Ken Hitchcock was coaching by then and was a major influence on Robin.

“That’s when my career turned around.”

Robin would score 29 goals and total 72 points in the 1985-86 season as the Blazers won another WHL championship and earned another trip to the Memorial Cup where they again came third. In Robin’s final year of junior eligibility at age 20, he put everything together and exploded for 57 goals in 62 games, standing out on a powerful Blazers team that scored a WHL record 496 goals and was led by Rob Brown, who piled up a league record 212 points in just 63 games, as well as future NHLers Greg Hawgood and Mark Recchi. Robin signed with Washington and went to their training camp that September.

A longshot to make the Capitals, he prepared himself to play for their farm team in Fort Wayne of the International Hockey League, but knew so little about Fort Wayne, he thought it was in Texas. “At least it will be warm!” he remembers thinking. Fort Worth, Texas is certainly sunny, but the stark Arctic-like cold of Fort Wayne, Indiana in the American Midwest was a shocking wake-up call.

So was what he encountered on the ice. Billed as a scorer, he struggled to find the net for the Komets and, to make matters worse, opponents targeted him as the only non-white player in the league. In his fourth game, he was challenged to a fight.

So was what he encountered on the ice. Billed as a scorer, he struggled to find the net for the Komets and, to make matters worse, opponents targeted him as the only non-white player in the league. In his fourth game, he was challenged to a fight.

“I went into the fight, but didn’t really know how to fight,” he recalled with a chuckle. “My uncles tried to teach me, but I didn’t know how. So I actually won it. Rob Laird [Fort Wayne’s coach] had been doubting me as a scorer, then said ‘This kid’s a fighter, not a goal scorer’ and changed my lines.”

Suddenly Robin found himself cast as a fighter.

“That year was just trial and error. I ended up scoring a few goals, got my hands back, but was just trying to survive. Trying to score, protect myself, and not get beat up. I think I had about 23 fights that year and won about half.”

He constantly felt he was a target and knew he had to be prepared to defend himself better. After an offseason of training in the boxing gym and working on his hands, in his second IHL season, this time in Baltimore with the Skipjacks, he piled up a very respectable 23 goals and over 200 penalty minutes, playing a solid, tough, two-way game, chipping in on offense and playing heavy when needed. In this way too, he was probably ahead of his time, tailor-made for the NHL of today that emphasizes speed and skill, but still values grit and toughness.

He constantly felt he was a target and knew he had to be prepared to defend himself better. After an offseason of training in the boxing gym and working on his hands, in his second IHL season, this time in Baltimore with the Skipjacks, he piled up a very respectable 23 goals and over 200 penalty minutes, playing a solid, tough, two-way game, chipping in on offense and playing heavy when needed. In this way too, he was probably ahead of his time, tailor-made for the NHL of today that emphasizes speed and skill, but still values grit and toughness.

“I was probably better suited to today’s game than the game in the late 1980s and early 1990s.”

Despite being a much bigger city than Fort Wayne, Baltimore was an even bigger adjustment off the ice. There were no other Indo-Canadians anywhere. He felt alone at times.

“They didn’t know what I was. They had no idea. I tried telling them I was from Canada or where Vancouver was. They thought maybe I lived in an igloo with polar bears. When I told them I was East Indian, they’d ask, ‘What tribe are you from?’ They thought I was everything from Italian to Greek to Iranian to whatever. Back then, they didn’t know what an East Indian person—or Indo-Canadian today—was. So after that, I just said, ‘I’m Canadian.’ That was good enough!”

It didn’t make things any easier for Robin, but his improving play earned respect from teammates and fans. On the road though, scoring goals and winning fights while being the only Indo-Canadian player anyone had ever seen on ice, drew the immediate ire of opponents and opposing fans alike, who baited him with racist insults. The fans in New Haven, Connecticut were the worst. “Those fans were wacked. Rednecks everywhere.”

Despite the abuse, Robin held his own and in his third year as a pro he made Washington’s roster out of training camp, which led to his NHL debut and that moment standing at the blue line in the Capital Center as the anthem played. It had been as difficult a road as that faced by any NHLer. Looking back, he thinks there are lessons to be learned from his story for young players today.

“A message from me to the boys is you have to be patient. If you get sent down, you have to be patient. You gotta work. It takes time.”

Other players of Indo-Canadian heritage have followed his trailblazing path to the NHL—former Canucks forward and current assistant coach Manny Malhotra and current Edmonton Oilers forward Jujhar Khaira from Surrey—and others have been drafted and played pro hockey—notably Ajay Baines, Prab Rai, and Kevin Sundher.

Today, Robin is the co-owner of his family’s trucking company, Marpole Transport, and you can often find him in rinks around the Lower Mainland coaching his teenage boys. Much of the blatant racism he faced has thankfully disappeared, but hints still appear from time to time. It should never happen. Hockey—and all sports—should be open and welcoming for all Canadians regardless of background. Things are improving, but more work still needs to be done. And this is why Robin’s story remains so important today as a reminder and an inspiration.

Robin Bawa will be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Pioneer category as part of the Class of 2020 Induction.