Jim Kojima: Riding the Judo Wave – 2023 Inductee Spotlight

April 8, 2023By Jason Beck

Jim Kojima turned 85 years old—or young—last month. I say young because Jim is more active in his lifelong sport of judo and his community than most people half his age or younger.

Working to document and share the stories of the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s Honoured Members for some time now, you get used to seeing individuals who have been actively involved in their sport for 30 or 40 years. Dedication to sport for that length of time is a remarkable achievement. Occasionally you find someone with a 50-year involvement and very rarely does a special person contribute for 60 years.

But 70 years? Find me another person who can match that. I can’t recall anyone in BC actively contributing to their sport for 70 consecutive years like Jim Yuzuru Kojima has done in judo. It was seven decades ago way back in 1953 that Jim first began competing as a young 15-year-old judoka with the newly formed Steveston Judo Club. Since then, he has been involved as an athlete, coach, referee, official, administrator, board member, and fundraiser—all as a volunteer too it should be pointed out. You can still find him twice a week down at the Steveston Martial Arts Center teaching judo to young kids in amongst his other responsibilities with Judo BC, Judo Canada, and various Richmond community groups.

Jim literally has devoted his entire adult life to raising the international profile of judo in BC and Canada unlike any other individual in this province and possibly this country’s history. He is remarkably humble and understated when discussing his life and career.

“I just think I was very fortunate,” he said in a recent interview. “I just like to ride this wave and keep going forward.”

“I just think I was very fortunate,” he said in a recent interview. “I just like to ride this wave and keep going forward.”

That wave carried him past terrible hardships early on and has taken him around the world spreading the good that judo and sport can bring to untold numbers of individuals and communities.

Born in Steveston, Jim was approaching his fourth birthday in early 1942 when in the aftermath of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour, the Canadian government forcibly relocated Canadian citizens of Japanese heritage away from the BC coast. Jim’s father and grandfather, both fishermen, had their fishing boats, equipment, and vehicles all confiscated by the Canadian government. Nothing was ever returned to them. Without any choice of where they would be moved to, the Kojimas were evacuated to Alberta.

“Many of the Japanese came to Canada with nothing,” said Jim. “They couldn’t speak the language. All they knew was to work hard and never give up. And to be proud of being Japanese. I remember my grandparents saying to me, ‘Never do anything to embarrass the Japanese race.’”

This wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last that the Kojimas—and many Japanese-Canadian families at that time—were forced to start out with nothing once again. Only four, Jim was too young to understand the hardships facing his family. In fact, one of his earliest memories is of the train trip east. It seemed like a great adventure at the time.

“We rode by train from Vancouver through the Rockies and I remember as a four-year-old my mother saying, ‘Another tunnel is coming! Another tunnel is coming.’”

When they arrived in Calgary, Jim’s parents thought it looked like a good place to live.

“But we boarded another train for Lethbridge and we got off the train with a number of other Japanese citizens. There were many farmers at the train station and they’d call out your name. ‘Kojima!’ And that’s the farm you went to. You didn’t have any choices.”

The Kojimas were placed on a very poor sugar beet farm owned by farmers Henry and Cora Blair. The Kojimas—Jim, his mother, father, grandmother, and two grandfathers—stayed there for five years, six of them living in a 10’x10’ chicken coop.

“It was cold through the wintertime,” remembered Jim. “Through the eaves the snow would come in, so my parents would be blocking it up with clothes and paper. But the Japanese people are very loyal people. My parents couldn’t go to the Blairs and say, ‘We want to leave.’ So we stayed there five years.”

They got used to the annual cycle of seasons: spring, summer, and in the fall taking the sugar beets to the factory. Then in the wintertime, Jim’s father worked at the sugar beet factory outside in the bitter cold putting sugar beets on a conveyor.

“The Japanese couldn’t go inside to have coffee or lunch. They had to stay outside all the time.”

There were some positive aspects to life there. The Blair family had four boys, two close in age to Jim.

“So I played with the kids on the farm. I went to school with them and so life for me was pretty normal.”

After the nuclear bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, World War II ended. But the hardships for many Japanese Canadians didn’t end there and continued on for many years.

After the nuclear bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, World War II ended. But the hardships for many Japanese Canadians didn’t end there and continued on for many years.

In 1946, the Canadian government gave the choice to Japanese Canadians to return to Japan if they wished. After being treated like prisoners in their own country, thousands did leave and Jim’s parents were amongst those who had initially decided to go.

“They had packed all their bags, everything of their worldly possessions, to go back to Japan. But Henry and Cora Blair convinced them that going back to Japan is going to be worse than what you have here in Canada, so they decided finally to stay.”

A year later in 1949, the Kojimas moved to Barnwell near Lethbridge and Taber for one year. Then they moved to Grand Forks in BC where Jim’s uncle lived. At the same time, the BC government was allowing some male Japanese fishermen to return without their families to fish on the BC coast. A year later, their families could join them. Jim’s family waited it out and returned as one back to Steveston in 1951, nine long years after they were forcibly uprooted.

“When they came back, they had nothing again. Three times, the Japanese first and second generation, had to start over from nothing. It’s just the Japanese nature to never give up, to persevere, to work hard, and keep your nose clean.”

Just because the war was over and they were home again didn’t mean the racism, much of it stirred up by the war, suddenly disappeared.

“There were many things left over from the war,” Jim remembered without going into detail. But you could hear some of the pain in his voice.

Anti-Japanese feeling certainly still existed amongst the general public in BC, some of it pre-dating WWII. But change was slowly happening. One change in Richmond was the integration of public schools. Previously, only Japanese families who owned property—and there were very few that did—could send their children to the public schools. Most Japanese kids in Richmond attended Japanese schools as a result. In 1950 that bylaw was eliminated and so Jim and many other returning Japanese children attended school with children from white families for the first time.

“Yes, there were some fights,” he remembered. “We were called ‘Japs’ and things like that, but nothing major. It didn’t last long because we all ended up playing sports together and doing different things together.”

One of the things that slowly helped bring a divided community back together was judo. And that was when Jim began riding the wave still carrying him to this day.

There were a number of black belts among the local fishermen in Steveston and after fishing season finished, ten of them decided to start a judo club. In September 1953, the Steveston Judo Club was founded. Jim, age 15 and having never tried judo before, was among the 80 inaugural club members.

“I remember doing break falls,” he recalled with a smile. “In those days we did break falls for three months before you ever learned to throw. When I was teaching later, people said to me, ‘Jim, you made us do break falls for three months.’ Well, that’s what we did! Why shouldn’t you?!”

At that time there were no judogis (the traditional judo uniform) available to buy locally.

“Our mothers took a 100lb rice sack and made our pants for our judo outfit,” Jim recalled. “Our tops were made out of canvas.”

Around 1956 Mikado Martial Arts Supplies on Hastings Street began bringing in judogis so the boys could do away with the rice sacks.

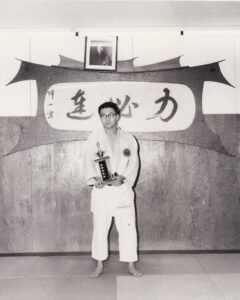

At first, the Steveston Judo Club used a room at the back of a theatre before moving on to other locations including the Red Cross hall, the old Buddhist temple near No.1 Road, and then Richmond’s new community center built in 1957, in Jim’s opinion another key moment in the post-war healing of his community. Years later, Jim helped raise nearly $100,000 through car washes, vegetable sales, and concerts to build the Steveston Martial Arts Center, which opened in 1972, the first dojo built in the traditional Japanese architectural style outside of Japan. The Steveston Judo Club has called this beautiful building home for over fifty years now. This first-class 10,000 square foot facility offering training in judo, karate, and kendo is a far cry from what the originals were forced to make do with. Early on there were no tatami (mats) for the floor, so they laid down sawdust and placed canvas over top.

At first, the Steveston Judo Club used a room at the back of a theatre before moving on to other locations including the Red Cross hall, the old Buddhist temple near No.1 Road, and then Richmond’s new community center built in 1957, in Jim’s opinion another key moment in the post-war healing of his community. Years later, Jim helped raise nearly $100,000 through car washes, vegetable sales, and concerts to build the Steveston Martial Arts Center, which opened in 1972, the first dojo built in the traditional Japanese architectural style outside of Japan. The Steveston Judo Club has called this beautiful building home for over fifty years now. This first-class 10,000 square foot facility offering training in judo, karate, and kendo is a far cry from what the originals were forced to make do with. Early on there were no tatami (mats) for the floor, so they laid down sawdust and placed canvas over top.

“It was hard!” laughed Jim. “Hard on the body, but we were young kids and it didn’t bother us, so that lasted for a couple years. Then our teachers, our sensei’s, went to Seattle and bought some used judo mats and that’s where we started to have tatami.”

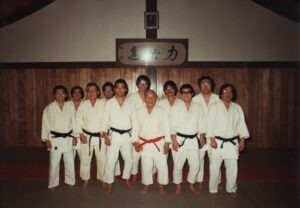

Of the 80 kids that started with the Steveston Judo Club at its inception in 1953, remarkably five original members are still volunteering their time coaching in the club today 70 years later. Besides Jim, the other four are: Martin Kuramoto, Isao Kuramoto, Art Nishi, and Hap Hirata.

“It’s really an incredible achievement,” Jim summed up. The Steveston Judo Club is very likely the only sports club or team in Canada today—possibly ever—that can claim to have five club members with 70 years of active service simultaneously.

“I was very fortunate because our teachers taught us—the five of us, for sure—in judo or in life, when you’re young you take everything you can from as many people as you can to be a better person or a better judoist or professional person. But someday in life you have to give back. And so there are five of us, still mobile, that are at the judo club giving back to the young kids.”

This has been just one way in which Jim has given back to the sport.

He actively competed in judo in the 1950s and 1960s, first earning his black belt in 1957 and by 2018 one of the rare few in Canada promoted to eighth degree (Hachidan) black belt. He and other Vancouver area judo athletes had to work hard to catch up to the stronger judo clubs in the BC Interior like Vernon, Kelowna, and Kamloops, which formed right after the war and had a head start in terms of development.

“Us young guys we’d go by CPR train to Kamloops or bus to Kelowna to compete with them,” he remembered. “They set the standards for us. We wanted to beat them all the time. It didn’t take us that long, maybe four years. I think it was also the numbers that we had [in the Lower Mainland], which surfaced a more elite group of athletes.”

Soon Jim became involved in other areas of judo and it was here that he truly distinguished himself.

In 1957, he first became involved with Judo BC as secretary-treasurer and has served on many provincial committees right up to the present day. That same year he also became heavily involved with Judo Canada and for the next 66 years served key roles on the referee committee, selection committee, and technical committee among many others. He served as Judo Canada’s vice-president for twenty years from 1968-88 and then as the organization’s president from 1988-94.

In 1957, he first became involved with Judo BC as secretary-treasurer and has served on many provincial committees right up to the present day. That same year he also became heavily involved with Judo Canada and for the next 66 years served key roles on the referee committee, selection committee, and technical committee among many others. He served as Judo Canada’s vice-president for twenty years from 1968-88 and then as the organization’s president from 1988-94.

The highlight of Jim’s term as president was undoubtedly when Canada hosted the 1993 World Judo Championships at Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum, the most prestigious judo event ever hosted in this country. The last time North America had hosted the worlds was back in 1967 in Salt Lake City, but Jim had built up enough support in Japan that key figures backed holding the championships in Canada. Jim convinced Konica to come on board as a sponsor and the event ended up turning a $40,000 profit. It helped that Montreal’s Nicholas Gill, coming off a bronze medal the year before at the Barcelona Olympics, moved up one podium place to world championship silver in the 86kg weight class in 1993.

“It ended up being a successful championship,” said Jim. “It was a well-run tournament and so we were very happy with the end result. It was a really good experience and a learning experience for Canadian judo in Canada.”

It remains the only time Canada has ever hosted the world judo championships to this day and the last time they were staged in North America.

Maybe the most impressive part of Jim’s career is what he has accomplished refereeing. He began refereeing locally in the late 1960s and by 1970 had received his Judo Canada national referee license. Two years later he received his Pan American Judo Union referee license. In 1974, he went to the Dominican Republic with 24 other referees from around the world, each vying for their International Judo Federation license.

received his Judo Canada national referee license. Two years later he received his Pan American Judo Union referee license. In 1974, he went to the Dominican Republic with 24 other referees from around the world, each vying for their International Judo Federation license.

“There were three people left on the seventh day and I knew I’d made it because the three of us were from different countries,” he remembered. With that, Jim became the first Canadian-born citizen to become qualified to referee in all international competitions up to and including the Olympic Games.

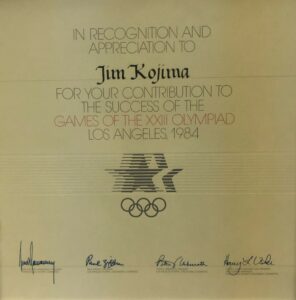

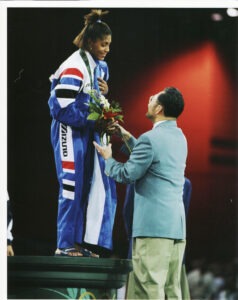

Over the next decade he established himself as one of the world’s top judo referees refereeing at competitions around the world. Among the highlights were refereeing at the men’s world championships in 1975 (Vienna; oversaw two of seven weight class finals), 1979 (Paris; in front of crowds of 10,000+), and 1981 (Maastricht, Netherlands). He also refereed at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal and the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. Later he was at the 1988 and 1992 Olympics as part of the International Judo Federation (IJF) Referee Commission and at the 1996 and 2000 Olympics as the IJF Referee Director, giving him participation at six different Olympic Games. Jim’s philosophy to refereeing judo was simple.

“You have to be ready and not biased,” he said. “It’s a tough situation because you don’t want to show bias but then you don’t want to be on the other side showing so much unbias that you put a fighter at a disadvantage. It’s a fine line.”

Jim’s already impressive refereeing resume would be even longer if not for the last-minute cancellation of the 1977 worlds in Barcelona (Jim was already in Spain when they were called off) and the western boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

One of his proudest contributions was refereeing at the first-ever women’s world championships in New York in 1980. In fact, when it comes to women’s judo Jim played a key role through Judo Canada and the IJF in helping increase the participation of women in the sport. Jim saw women’s participation as key for the growth of the sport as a whole.

One of his proudest contributions was refereeing at the first-ever women’s world championships in New York in 1980. In fact, when it comes to women’s judo Jim played a key role through Judo Canada and the IJF in helping increase the participation of women in the sport. Jim saw women’s participation as key for the growth of the sport as a whole.

“If you teach women good judo and good things about judo, women have kids,” he explained. “They’ll send their kids to judo. So, you have to promote that.”

While men’s judo became an Olympic sport in 1964, women’s judo wasn’t included on the Olympic schedule until 1992. Whereas at one time there wasn’t a single female member of the Steveston Judo Club as just one example, now participation worldwide is almost at 50% men and 50% women today.

In 1995 after his term as Judo Canada president came to an end, Jim was elected as the IJF’s Referee Director, a six-year position where he’d oversee judo refereeing worldwide. In order to fulfill the demands of this position, Jim retired from his job at Tree Island Steel in Richmond (owned by current BC Lions owner Amar Doman) where he’d worked for 30 years and he and his wife lived on his pension. For the next six years, Jim travelled an average of 220 days of the year out of the country attending championships, tournaments, conferences, examinations, and seminars all over the world.

“One time I came home from Japan about noon and by four o’clock I was on a flight to Argentina,” he laughed at the memory. “So, I just came home, changed my suitcase and clothes, and I was off again. Wow.”

By the end of his term as IJF Referee Director in 2001, Jim had been involved in 22 different IJF world championships during his career. To date, he has visited 78 countries and all seven continents.

“Poor countries. Rich countries. Not-so-rich countries. I think I’ve learned a lot of how to be a human being.”

He cites Paris and Vienna as two of his favourite places he has been lucky enough to visit through judo.

The awards Jim has received over the course of his career are no less impressive. In 1983 he received the Order of Canada. In 2011 he was honoured with Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun. In 2001, he was awarded the IJF Gold Medal for Merit and named an IJF Honourary Life Member. Judo Canada named him a Life Member in 2004 and inducted him into their Hall of Fame in 2006. There have been many, many other awards in addition to these.

“I have won so many awards…I keep telling I don’t want any more awards,” he laughed. In November, there will be one more when Jim will travel to Wakayama in Japan, Richmond’s sister city, to receive the highest cultural award given out in Wakayama.

“I have won so many awards…I keep telling I don’t want any more awards,” he laughed. In November, there will be one more when Jim will travel to Wakayama in Japan, Richmond’s sister city, to receive the highest cultural award given out in Wakayama.

All the awards are well deserved considering the impact Jim has had on judo not just here in Canada, but worldwide. It’s sometimes hard even for those heavily involved in the judo community to fully grasp how respected Jim is worldwide, particularly in the traditional home of judo in Japan. Maybe no anecdote illustrates that better than one shared by current president of the Steveston Judo Club, Alan Sakai, who competed for Canada in judo at the 1972 Olympics.

“I was privileged to participate on a training tour to Japan in 2018,” Sakai explained. “Wherever we went Jim was received with great honour. We visited and trained at the Tokai University Judo training centre, which currently houses the Japanese Olympic Team. I noticed that in the great hall there were photos of significant contributors to the sport of Judo. There were only two foreign Judoka featured, and one of them was Jim Kojima.”

Over the past 70 years, he has witnessed many changes and much growth in the sport.

“Judo has evolved somewhat from the old traditions when there were no weight divisions. Everybody fought everybody. It was an open division. The creation of weight classes meant the different technique of a small man fighting a bigger man was no longer used. You have to have speed and good technique to take the bigger man down. Whereas today you’re fighting your same weights. I think the level of judo technically has gone down a little bit. I wouldn’t say a lot, but a little bit.”

In other areas, it has grown leaps and bounds. The growth of women’s participation has cemented judo as an international sport for all. Approximately 188 countries worldwide participate in judo, one of the highest participation rates of any sport in the world. Jim takes the most pleasure from seeing the small changes in young kids as they learn the sport.

“What I enjoy most is the behaviour of the kids, from the start of judo to six months later how much respect they have and their manners. The bow is very important to us, paying respect not only to your fellow athletes but your teachers. We teach them that the same respect has to go to the mayor or your grandfather or whoever. We teach them in judo not to walk in front of people, walk behind people and things like that. When I see that, I think, ‘Wiii-aayyy!’”

“What I enjoy most is the behaviour of the kids, from the start of judo to six months later how much respect they have and their manners. The bow is very important to us, paying respect not only to your fellow athletes but your teachers. We teach them that the same respect has to go to the mayor or your grandfather or whoever. We teach them in judo not to walk in front of people, walk behind people and things like that. When I see that, I think, ‘Wiii-aayyy!’”

He laughs approvingly at that last thought before shifting to his proudest accomplishment.

“Seeing the Steveston Judo Club operating the way it is operating from Day One. We are all volunteers there. All the teachers that come in and teach from Monday to Friday, weekends in coaching BC team members and things like that, it’s just nice to see that we can still run a club in Canada as volunteers. Because I think when you start paying it brings a different dynamic. Today, everybody at our club is a volunteer. All the money we get from membership and monthly dues all goes back into the judo club. If we send kids to Montreal for tournaments or world championships elsewhere, it pays for their trip. None of the money goes back to the teachers. That’s what we dread: twenty years from now, will there still be volunteerism?”

there. All the teachers that come in and teach from Monday to Friday, weekends in coaching BC team members and things like that, it’s just nice to see that we can still run a club in Canada as volunteers. Because I think when you start paying it brings a different dynamic. Today, everybody at our club is a volunteer. All the money we get from membership and monthly dues all goes back into the judo club. If we send kids to Montreal for tournaments or world championships elsewhere, it pays for their trip. None of the money goes back to the teachers. That’s what we dread: twenty years from now, will there still be volunteerism?”

New club members and coaches have no better example to follow than Jim and his four fellow original club members, still active a remarkable seven decades after first becoming involved. When our talk shifts to his upcoming induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame, his voice grows softer and you can sense what this honour means to someone from a sport that often doesn’t get the recognition it deserves in Canada.

“It feels very humbling. When I look at the list of people that are in the Hall, to be honoured in the Hall with them is a real honour and a pleasure. I feel very humbled about that.”

As part of the Class of 2023, Jim Kojima was formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Builder-Coach category at the annual Induction Gala held June 1, 2023 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.