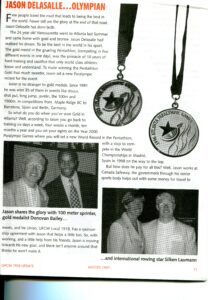

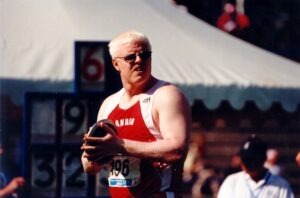

Jason Delesalle: Multi-Events Master – 2021 Inductee Spotlight

May 30, 2022By Jason Beck

No one had to tell Jason Delesalle that he’d made it. Not when he’d just won the Paralympic gold medal in the pentathlon (P12 class) with a Games record point total. After all Jason had been through to get there, he knew what it meant.

But when that someone is Donovan Bailey it certainly doesn’t hurt.

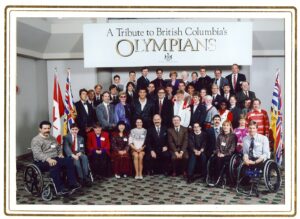

It happened after Atlanta 1996 when all Canadian Olympic and Paralympic athletes were invited to Ottawa to be recognized together for the first time with their names read out on the floor of the House of Commons. Afterwards, Jason was having a conversation with the newly crowned fastest man in the world Bailey, fresh off winning two Olympic gold medals and a new 100m world record. They were comparing notes about the differences between the Olympics and Paralympics when someone came to pull Donovan away for a photo with the entire Canadian 4x100m relay team.

“Hold on, just a sec, I’m talking to an athlete,” he said.

“Yeah, he’s talking to a Paralympic athlete,” piped up Jason.

“Yeah, he’s talking to a Paralympic athlete,” piped up Jason.

“What’s that word?” Bailey asked.

“Oh, Paralympic?” Jason replied.

“No,” said Bailey. “Don’t say that word. We’re all athletes here.”

“So he grabbed me and took me over and I had my picture taken with all the 4x100m relay guys,” recalled Jason. “That was a big highlight for me. Talking to someone like Donovan and having him say that. That’s recognition right there. You want to talk about inclusion? There you go. You just got it from one of the world’s best.”

As is his way, Jason is being modest. It was one of the world’s best athletes acknowledging one of the world’s best athletes if we’re being precise. For the better part of a decade Jason Delesalle was among the best multi-event athletes on the planet and his story deserves to be better known by all Canadians.

Jason grew up in Invermere in BC’s southeastern corner near the Alberta border. From a young age, he always had an interest in sports.

“I was always athletic,” he said in a recent phone interview from his current home in New Westminster. “I was always doing things. I waterskied. I swam in my grandpa’s pool every day in the summer. We lived on the outskirts of town so there were always trails we were running around and running up hills as kids.”

In a way one of his earliest sports memories from the annual elementary school sports day provided a taste of the experience Jason would later have as a world-class multi-events athlete competing in multiple track and field events at once.

“I always liked those June sports days, the competition of it, plus it was sponsored by Super Socco orange drink!” he recalled with a laugh. “But I really liked the structure of it. The fact that over in that corner was throwing bean bags, over this side was running and long jumping. Then they had the three-legged races down the field. That’s kind of what got me really excited for sport.”

When Jason was 12 his parents split up and he and his mom moved north with his stepdad to Fort St. John for a year before settling in Tumbler Ridge to the south where Jason finished high school. At Tumbler Ridge Secondary Jason played basketball, volleyball, and soccer and became interested in weightlifting, developing a foundation of strength that later helped him in throwing events. His PE teachers, Steven Bentley and Dan Lapacka helped him look at sport in a more serious way. It was also there that he was first introduced to track and field. The facilities and equipment were limited you could say, but that didn’t stop Jason or his teammates.

“There was just a grass field, no track or anything,” he remembered. “We had one or two javelins that were probably as crooked as canes. A couple rubber discuses because we couldn’t afford a good discus. Iron balls that were probably fish weights. When you hear stories of kids growing up with nothing starting in a dirt field and making the Olympics or Paralympics, biggest show in the world for amateur sport, it’s kind of like the rags to riches thing. That’s what it was like in Tumbler Ridge.”

“There was just a grass field, no track or anything,” he remembered. “We had one or two javelins that were probably as crooked as canes. A couple rubber discuses because we couldn’t afford a good discus. Iron balls that were probably fish weights. When you hear stories of kids growing up with nothing starting in a dirt field and making the Olympics or Paralympics, biggest show in the world for amateur sport, it’s kind of like the rags to riches thing. That’s what it was like in Tumbler Ridge.”

Jason had been born with impaired vision but wearing glasses his sight was right on the cusp of the legal requirement for driving. It meant that he could compete in any sport without a guide and it certainly didn’t slow him down at all. While still competing in high school, Jason’s athletic ability landed him on the radar of the BC Blind Sports and Recreation Association, who suggested he travel down to the Lower Mainland for competitions including the 1988 provincial championships for athletes with a disability. Surprising everyone including himself, Jason won gold in the long jump and took silver in both the 100m and 200m. Not long after he followed that up with a silver in the 200m and bronze in the 100m at the Canadian nationals at Simon Fraser University. Then in 1990 at the World Youth Games in Saint-Etienne, France, he won silver in the 100m and 200m and took bronze in the long jump in his first opportunity competing for Canada internationally.

By the 1991 BC provincial championships held at the Apple Bowl in Kelowna, Jason was clearly a rising star in Canadian para athletics. At that meet he would win five gold medals (100m, 200m, javelin, shot put, long jump) and one silver (discus). Remarkably that wasn’t even the most significant thing about this meet for him. It was here that Jason first met Don Steen, a 2003 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee and the coach who would have the most profound influence upon Jason’s life and athletic career. Don, at one time a top Canadian decathlete himself and by then a legendary coach, was a VIP at the meet when he saw Jason competing and began giving him coaching tips.

“He said, ‘When’s your next event?’ I had shot put in like an hour. ‘Ok meet me over there in half an hour.’ So then I’d go there and he’d show me a couple things. And then I win the shot put. He did the same thing with me before the javelin and I won that. So we did that around the track that day and then we started talking. He said, ‘Well if you ever get down to Vancouver, I’ll coach you.’”

Not long after, Jason’s mom was driving him down to Burnaby to live with a family Don knew two blocks from Burnaby Central High School where they would train and work together for the next 13 years.

“Burnaby Central became my home,” said Jason.

He quickly settled into a new routine training six days a week, with periods leading up to a key competition increasing to twice a day workouts. Burnaby Central’s long-time track coach, Ken Taylor would coach Jason on sprints during the day and then Don arrived at night for throwing workouts. One winter Jason worked with coach Derek Evely as well. Needless to say the old storage container converted into a locker and equipment room at Burnaby Central (still there today) quickly began to feel like home for Jason. He and Don also settled into a strong athlete-coach partnership. For the first time in Jason’s athletic career everything was planned out in a detailed training and competition program.

He quickly settled into a new routine training six days a week, with periods leading up to a key competition increasing to twice a day workouts. Burnaby Central’s long-time track coach, Ken Taylor would coach Jason on sprints during the day and then Don arrived at night for throwing workouts. One winter Jason worked with coach Derek Evely as well. Needless to say the old storage container converted into a locker and equipment room at Burnaby Central (still there today) quickly began to feel like home for Jason. He and Don also settled into a strong athlete-coach partnership. For the first time in Jason’s athletic career everything was planned out in a detailed training and competition program.

“Don’s a planner,” explained Jason. “He likes to plan. He was very structured, almost to ‘this day we’re doing this, this day we’re doing that’ and it’s in the program. I had been doing all kinds of different events before meeting Don. I had no structure. He helped me a lot that way. I thrived on that. I loved it.”

While Jason was soaking up Don’s coaching wisdom and support like a sponge, Don was also learning too.

“Don was very patient. He was working with an athlete with a disability. He often wasn’t sure what I could and couldn’t do. So it was also a testing ground for both me and him. He wasn’t sure what my abilities are and I’m learning the sport in a structured way, so it was all learning for both of us.”

Through the annual cycle of pre-season, winter training, cross-country training, and then aiming to peak twice in major events each year—usually a big qualifying meet and then a major international event—Don learned what made Jason tick and how to get the best out of him.

“It was fun,” chuckled Jason. “Don would trick me into some things.” A typical exchange might go something like this:

Don: “Oh, you probably can’t do this.”

Jason: “What do you mean?!”

Don: “Well, I wanted to try something but I’m not sure you can do it.”

Jason: “Well, what is it?”

Don: “Oh, I want you to do this.”

Jason: “Well, let me try!”

“So I’d do it,” Jason laughed. “And that was his way of getting me to do stuff sometimes. He’d just inadvertently try to challenge me about it. So I’d have to prove this guy wrong that I can do this. Later on I’d catch on to what he was doing. I’d say, ‘Really Don, you can just ask me to do it!’ So, it was kind of a fun joke between us.”

It was the ideal situation for Jason to improve and succeed. He was training with better equipment, had access to better facilities, and he had an enthusiastic, supportive, well-planned coach working with him.

It was the ideal situation for Jason to improve and succeed. He was training with better equipment, had access to better facilities, and he had an enthusiastic, supportive, well-planned coach working with him.

“And I had a year and a half to get myself in shape to compete in the Paralympics in Barcelona.”

By the time Jason walked into Barcelona’s Estadi Olímpic de Montjuïc with his Canadian teammates during the Opening Ceremony of the 1992 Paralympic Games cheered on by a crowd of 65,000 waving cardboard hands as if to say ‘hello’, he knew he’d made the right decision to commit himself to this.

“It was hook, line, and sinker for me. This is it. This is what I want to do. I don’t think I picked my jaw up for about two hours. I just had a grin from ear to ear. ‘This is awesome! I’m not doing anything else but this!’ That was probably the end of my decision of doing any other sports or anything else. I was on cloud nine at those Paralympics.”

Jason rode that feeling to a silver medal in the javelin (B3 class) throwing 48.34m and finishing ninth overall in the 100m just missing the final by two hundredths of a second. He likely would have won another medal in the pentathlon if it hadn’t been cancelled shortly before the Games when several participants were unable to travel to Spain.

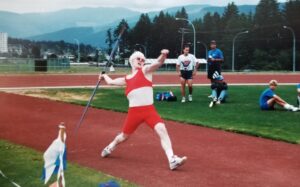

Speaking of which, recognizing Jason’s all-round athletic ability, at Don’s urging the pentathlon had quickly become Jason’s focus. The Paralympic pentathlon in the P12 classification consisted of five events (100m, javelin, long jump, discus, 1500m) with points scored for an athlete’s performance in each event and totaled up for a combined score. It took some convincing, but at the 1991 Foresters Games, the national championships for athletes with a disability, Jason finally agreed to give it a try. Up until then, he had only been competing in individual events, some of which were part of the pentathlon, but he had never run a 1500m for instance.

“Of course, every athlete is scared of a 1500m especially in the multi’s,” laughed Jason. “Don said, ‘I think you’d be good at it.’ And he was a decathlete himself, coached his son Dave Steen [a 1991 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee], and he’s passionate about it, so I thought why not?”

At that time France Gagné, an impressively built pentathlete, was the national pentathlon champion in Jason’s class. Jason and Franz ended up battling head-to-head, Jason winning one event, then Gagné winning the next. You know where this is going: it came down to the 1500m, of course, to decide the championship.

“I’m just like, ‘Oh god, here we go,’” recalled Jason. “I’ve never ran a 1500. I don’t know what to expect. So, I was super nervous.”

Jason had to beat Gagné by a certain amount of time to move into the gold medal position. Don’s game plan for him was to hang on the backside of Gagné as much as possible and then on the final lap try to pass him with whatever he had left.

Jason had to beat Gagné by a certain amount of time to move into the gold medal position. Don’s game plan for him was to hang on the backside of Gagné as much as possible and then on the final lap try to pass him with whatever he had left.

Although initially shocked at the pace of the race, Jason “surprised himself” by staying with Gagné and then with about 300m to go, he saw Don standing trackside and yelling, ‘Okay, let’s go!’

“So I pulled up to France on the back side and coming out of the final corner he edged out to make it hard for me to pass him, but I did get by going wide. He was on my heels but I just bore down and came across in front. I was wondering ‘Did I do it? Did I do it?’ This point system was all new to me.”

Sure enough, Jason had beaten Gagné for the national title and had set a new national pentathlon record in the process.

“So I surprised myself,” he said proudly.

Jason would later win the national pentathlon championship two more times during his career in 1995 and 1996.

The 1994 IPC World Athletics Championships in Berlin were his first opportunity to contest the pentathlon internationally. Competing in the famed Olympiastadion where the 1936 Olympics had been held and Jesse Owens wrote himself into history, Jason too wrote his own name into the record books. After winning a silver medal in the javelin (best throw: 48.42m), he battled through the 42-degree Celsius heatwave scorching Berlin to become world champion in the pentathlon scoring a total of 2970 points, over 250 points ahead of his nearest competition.

Next up was the 1996 Paralympics in Atlanta. And for the first time Jason’s mom and stepdad travelled to watch him compete.

“That was huge for me. I was walking into Atlanta pretty pumped and I wanted to do well for them of course. But I was really ready for Atlanta.”

Jason’s focus couldn’t even be shaken by one of the more negative aspects associated with the Paralympics then—and still present today to some degree.

“A lot of it comes down to money. When the Olympics are on, everything is done up right. But when the Paralympics come along some of those things go away and there’s a difference. As Paralympic athletes we really don’t care, we’re there to compete, have a good experience, and do our best in sport. But media are leaving the city and don’t want to cover the Paralympics. The facilities change a little bit. Our cafeteria in the Athletes Village was a big tent set up in the parking lot of the university where before it was a full facility for the Olympics. Each Olympic athlete had an AT&T phone in their dorm room that they could dial long distance free of charge to their family back home. They pulled all of those out for the Paralympics. It didn’t bother me, didn’t phase me at all because I was just ready and psyched for the competition. I was more focused than I had ever been.”

“A lot of it comes down to money. When the Olympics are on, everything is done up right. But when the Paralympics come along some of those things go away and there’s a difference. As Paralympic athletes we really don’t care, we’re there to compete, have a good experience, and do our best in sport. But media are leaving the city and don’t want to cover the Paralympics. The facilities change a little bit. Our cafeteria in the Athletes Village was a big tent set up in the parking lot of the university where before it was a full facility for the Olympics. Each Olympic athlete had an AT&T phone in their dorm room that they could dial long distance free of charge to their family back home. They pulled all of those out for the Paralympics. It didn’t bother me, didn’t phase me at all because I was just ready and psyched for the competition. I was more focused than I had ever been.”

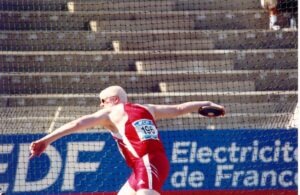

He began the Games with a bronze medal in the discus (F12 class) with a best throw of 42.36m. Then came the pentathlon.

During the morning session in Atlanta’s 85,000-seat Centennial Olympic Stadium (later Turner Field and today known as Center Parc Stadium) with his parents and coach Don watching, Jason was performing well and sat amongst the top three. During the break before the competition’s afternoon session when most other competitors left the stadium, he stayed behind.

“I snuck back into the stands of the stadium, which were empty, and there was my focus moment, my zen moment. Sitting in that stadium, just taking it all in, nobody in it, being focused on the afternoon session and knowing I had to win this. And that afternoon? Stellar afternoon.”

You could say that again.

As it so often does in multi-event competitions, it came down to the final event, the 1500m. Jason was sitting in the bronze medal position. Before the race he and Don ran through the various scenarios on what time Jason had to run and which competitors he had to beat by how much to maintain his position or move up on the podium. He felt moving up to silver was possible but wasn’t sure he could catch the leader for gold. He also knew other competitors just behind him were gunning for the podium too like Belgium’s Kurt van Raefelghem. Jason’s plan was to stick with Eddie Munro, an American competitor known to be strong in the 1500m and expected to lead. Let’s allow Jason to take us through the description of what happened next and, frankly, if you don’t get goosebumps by the end of the next few paragraphs, you might want to check your pulse.

“I’m in behind Eddie and he pulls us around the track on the first lap. Holy crap, it was so fast. We were just hanging on as much as we could. The guys that I had to beat were behind me. I was still behind Eddie when we get down to the bell lap. I heard Kurt behind me and he says, ‘Go get him!’ Because Eddie was pulling away from us. So I started to. And, of course, on the back straight, there’s Don, 300m to go yelling at me: ‘HOW BAD DO YOU WANT IT?!?!’ In the stadium you can’t hear anything with the crowd screaming. But oddly enough, I heard Don. ‘HOW BAD DO YOU WANT IT?!’

“Eddie was way up there, but I just bore down as best as I could on that back stretch. Of course, Eddie being American, all you hear from the stadium is ‘USA! USA!’ That was just fueling me. I came around the corner and I swear I was running on air. It felt so good, but it hurt at the same time. I was pulling in Eddie on the home stretch! I was pulling him in! He was dying. I didn’t beat him. I got up behind him, almost 8-10 meters behind him. Don said if I had another 10 meters, I would have caught him. And I crossed the line and I looked at the clock. My brain was mush. My body is mush. I’m done. I looked behind me and the guy I had to beat for silver was way back there. I was happy. I got silver. Yeah! I was pretty stoked. My parents are there, first time seeing me compete and I got the silver medal. [long pause] This is choking me up just today, wow!

“Eddie was way up there, but I just bore down as best as I could on that back stretch. Of course, Eddie being American, all you hear from the stadium is ‘USA! USA!’ That was just fueling me. I came around the corner and I swear I was running on air. It felt so good, but it hurt at the same time. I was pulling in Eddie on the home stretch! I was pulling him in! He was dying. I didn’t beat him. I got up behind him, almost 8-10 meters behind him. Don said if I had another 10 meters, I would have caught him. And I crossed the line and I looked at the clock. My brain was mush. My body is mush. I’m done. I looked behind me and the guy I had to beat for silver was way back there. I was happy. I got silver. Yeah! I was pretty stoked. My parents are there, first time seeing me compete and I got the silver medal. [long pause] This is choking me up just today, wow!

“Oh, but it gets better. So I know I have silver and of course we get ushered into the call room and we’re waiting for the final results. We know they’re going to call the three medal winners out to be tested and then ushered to the medal ceremony. So this poor little girl, who we all towered over, is sent into the tent under the stadium to get us and she says, ‘Gold, Jason Delesalle, please come with me.’ I was like, ‘What?! Excuse me?!’ But I couldn’t believe it. I did it!”

Jason was Paralympic champion in the men’s P12 pentathlon with a Paralympic record total of 3050 points. He finished just ten points ahead of Belgium’s van Raefelghem, the barest of margins.

“If you know multi-events, ten points is nothing.”

While they were holding Jason and the other medalists for testing and the medal ceremony, he managed to sneak out to soak up a few moments to celebrate with his parents and Don who had been with him every step of the journey to this point.

“That was definitely the highlight of my career,” he said his voice heavy with emotion.

Wearing his Paralympic gold medal around his neck on the podium was a surreal moment he won’t ever forget.

“To see yourself on the jumbotron at the other side of the stadium—I could actually see it—Oh Canada is playing, the flag’s being raised, and of course who is going through your head at that time: my parents, my coach, and my grandpa. Who do you thank? Who were those people that were there? That’s next level. My grandpa always said he was going to build me a 100m track where I could run. He always said, ‘You gotta get that ten seconds.’ Well, I never did run ten seconds, but I got the gold.”

After receiving the BC Athletics Award for top male athlete with a disability for the second year in a row and, of course, that ultimate compliment from Donovan Bailey we highlighted off the top, Jason returned to the IPC World Athletics Championships in Madrid in 1998 and took silver in both the pentathlon and javelin. Despite battling nagging injuries, two years later Jason was back for his third Paralympic Games in Sydney, Australia. As the defending Paralympic champion in the pentathlon, he was the favourite to repeat and he carried all the pressure and expectations that went along with that. In the pentathlon’s opening event, the long jump, on his final run-through Jason badly pulled his hamstring. After consulting with Don, he made the excruciating decision to drop out of the competition.

“That was hard. I did not want to leave. I was so mad. I didn’t want to leave the field of play. I finally had to come to terms with that and leave. And I like to say that there is a little garbage can in the tunnel in Sydney that was feeling the pain of my wrath because I was so upset.”

“That was hard. I did not want to leave. I was so mad. I didn’t want to leave the field of play. I finally had to come to terms with that and leave. And I like to say that there is a little garbage can in the tunnel in Sydney that was feeling the pain of my wrath because I was so upset.”

But Jason’s Games weren’t done yet.

“Took me a few hours to get my head straight and realize, it’s sport. It happens. You can’t change it. I had to switch gears because I was in the open discus competition two days later.”

Every three hours for the next two days the Canadian Paralympic team doctors and physiotherapists all went to work on Jason’s leg, trying to give him a chance to compete.

“Massage, acupuncture, electrodes, tense machine, ice baths, differential, walking on it, taping it—whatever it was, we did it. To get me back into some sort of shape so I could throw the discus. God love those people, they know their stuff, they got me there.”

His leg heavily taped up, he could stand on it and spin, enough to be able to compete, which he did admirably given the circumstances. Jason ended up finishing seventh overall.

“Sydney was a bit of a heartbreaker. I walked out of there and I was humble. I battled an injury. I competed. I did my best. The result was not desired, but it happens in sport.”

The injuries continued to nag at Jason over the next few years, but he soldiered on. After a sixth-place finish in discus with an injured shoulder at the 2002 IPC World Athletics Championships in Lille, France, he won a bronze medal in the same event at the 2003 IBSA World Championships in Quebec City. In 2004 at the Canadian Paralympic trials, he earned a silver medal in the discus despite battling a terrible back injury. He missed the qualifying standard to go to the Athens Paralympics by just 30cm. With the injuries piling up and no end in sight, Jason made the difficult decision to retire from competition.

“You begin to spend more time on the rehab than you do on the training and competing.”

“You begin to spend more time on the rehab than you do on the training and competing.”

After a break, in 2007 Jason turned to coaching young throwers at the Royal City Track Club, where he continues to coach to this day. The funny thing is even though the club is based in New Westminster, the city doesn’t have a dedicated throwing facility, so fittingly, Jason is back at the place that holds so many memories and meaning for him.

“So here I am, back again, at Burnaby Central after so many years training there, now coaching at a throwing field designed by Don for the last few years. It’s like coming home.”

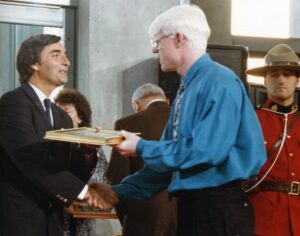

Since retirement Jason has been inducted into the Tumbler Ridge Sports Hall of Fame in 2007 and the Burnaby Sports Hall of Fame in 2011. His BC Sports Hall of Fame induction will complete the hat trick.

“It’s an absolute honour,” he said. “We’re talking about inclusion and so to be a Paralympic athlete inducted with the likes of, say, Gino Odjick or these past recipients is an absolute honour. And it’s like the cap of the career where you’ve put in the time and dedication, you’ve done your best and to be recognized—it’s the cherry on the top of a beautiful cake. It is the ultimate recognition to be honoured for something you did twenty or thirty years ago and it holds weight today. I’m tickled pink to be inducted and very humbled.”

As part of the Class of 2021, Jason Delesalle will be formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Athlete category at the annual Induction Gala to be held June 9, 2022 at the Vancouver Convention Centre.