Jaimie Borisoff: Undisputed Floor General – 2023 Inductee Spotlight

July 6, 2023By Jason Beck

When Jaimie Borisoff was attending Queen Elizabeth Secondary in Surrey in the mid-1980s, he looked up to two of the school’s star athletes. One was Laurier Primeau, who later became one of Canada’s top 400m hurdlers and is currently UBC’s track and field coach. The other was Paul McCallum, who had a long career as one of the CFL’s best kickers and won two Grey Cups with the BC Lions. And then there was Jaimie himself, who later went on to be among the best wheelchair basketball players in the world over a long international career representing Canada.

When Jaimie Borisoff was attending Queen Elizabeth Secondary in Surrey in the mid-1980s, he looked up to two of the school’s star athletes. One was Laurier Primeau, who later became one of Canada’s top 400m hurdlers and is currently UBC’s track and field coach. The other was Paul McCallum, who had a long career as one of the CFL’s best kickers and won two Grey Cups with the BC Lions. And then there was Jaimie himself, who later went on to be among the best wheelchair basketball players in the world over a long international career representing Canada.

For any BC high school to have even one athlete of this calibre in a generation would be noteworthy, but three at once might be some kind of record. And while Jaimie himself may have looked up to his fellow Queen Elizabeth classmates, as we’ll soon see here, his remarkable career turned out to be the best of the bunch.

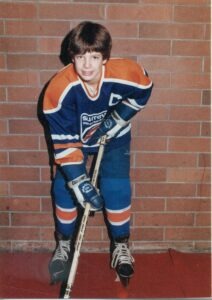

Born in New Westminster, Jaimie grew up in Surrey on the ball fields playing for Whalley Little League and in the city’s rinks skating through the Surrey Minor Hockey Association age levels. Interesting considering what came later for him in sport, he didn’t ever play organized basketball in his youth, but did play ‘21’ for fun with friends and was a fan of Michael Jordan.

Born in New Westminster, Jaimie grew up in Surrey on the ball fields playing for Whalley Little League and in the city’s rinks skating through the Surrey Minor Hockey Association age levels. Interesting considering what came later for him in sport, he didn’t ever play organized basketball in his youth, but did play ‘21’ for fun with friends and was a fan of Michael Jordan.

Everything changed in the summer of 1989 after Jaimie’s first year of university at UBC. As a summer job, he was working for a fellow who constructed school playgrounds. After a long, hot July day working outside, his boss decided as he drove Jaimie home that they should stop off at a pub for a cold beer. Unfortunately, you can guess what happened next.

“We stayed way too long and drank way too much,” recalled Jaimie in an interview at the BC Sports Hall of Fame earlier this year. “He basically ended up putting me in the truck, we headed off, and we didn’t get too far. I was probably the median spinal cord injury at the time: 19-year-old male in a drinking and driving auto accident.”

Their truck went off River Road in Delta and slammed into a telephone pole. Jaimie’s boss was killed, while Jaimie suffered a severe spinal cord injury (fractures of his sternum and Thoracic 4 vertebrae) that left him paralyzed from the chest down. He spent about five weeks recovering at Shaughnessy Hospital and then moved over to GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre to continue his recovery.

You could fill a small hall of fame just with the number of exceptional athletes Rick Hansen has visited in the hospital shortly after a terrible accident and Jaimie was another on that list. Rick visited him while he was still in the acute ward. Not only was the visit from the Man in Motion himself uplifting in the wake of the accident, but it was even more meaningful given that when Jaimie was named the top Grade 12 math student in his school, his gift was a copy of Rick’s book, so he was already familiar with Rick’s remarkable story.

You could fill a small hall of fame just with the number of exceptional athletes Rick Hansen has visited in the hospital shortly after a terrible accident and Jaimie was another on that list. Rick visited him while he was still in the acute ward. Not only was the visit from the Man in Motion himself uplifting in the wake of the accident, but it was even more meaningful given that when Jaimie was named the top Grade 12 math student in his school, his gift was a copy of Rick’s book, so he was already familiar with Rick’s remarkable story.

Not long after, Jaimie began writing his own remarkable tale. In 1989 there weren’t a lot of formal sport opportunities available to a young athlete in the wake of a major spinal cord injury like his. In BC, the two main options were wheelchair athletics, either racing on the track or road, or wheelchair basketball.

“Individual sports were not my thing,” Jaimie said. “I always liked team sports. I didn’t have that mindset to get up on your own each morning and do your miles. But I’d go to a team practice all the time. I loved it. I don’t know if it’s the group, the camaraderie, but that was always my thing.”

That same summer, while Jaimie was rehabbing at GF Strong, a fellow named Dave Schneider had returned for some rehab after sustaining an injury many years earlier. Dave had a car and Jaimie was beginning to suffer from cabin fever, so he accompanied Dave one day to a little gym at Vancouver’s Jericho Community Centre where there was a wheelchair basketball program.

“I played there for the next ten years after that,” Jaimie said. “That was how I got involved with wheelchair basketball and just never left.”

“I played there for the next ten years after that,” Jaimie said. “That was how I got involved with wheelchair basketball and just never left.”

He quickly fell in love with the game, which he discovered had similarities to hockey. He also made new friends and initially heading down to Jericho to play basketball was something that gave him some direction after the accident had abruptly turned everything upside down.

“It was a team sport that had elements of hockey to it,” he explained. “Five people on your team against five people. Elements of coverage and locations on the court, timing things. It was very natural and there was a flow to it. The team aspect was very easy and one of my strengths. Then it was just about getting some fitness and some skill.”

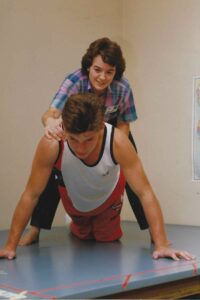

While back at UBC with a full course load—remarkably just six months after the accident—Jaimie kept playing out of Jericho twice a week (and later at Douglas College two-to-three times a week in the program Tim Frick ran there along with Joe Higgins, who had just become head coach of the men’s national team) as well as in various Lower Mainland wheelchair basketball leagues that ranged from two to four teams year-to-year and weekend tournaments throughout the province. One of his first teams was the SurDel Shooters run by the great Daniel Wesley, one of Canada’s most decorated Paralympic athletes having won a dozen medals while competing at both the Summer and Winter Paralympics.

Playing with the Shooters exposed Jaimie to another level of competition. Some of his teammates were top international players on the Canadian national men’s wheelchair basketball team like John Lundie and Murray Brown. When you’re new to a sport and playing with elite athletes, it’s bound to be a steep learning curve as it was for Jaimie at first. One time in just a simple lay-up line drill John became so fed up with Jaimie he made him switch spots so he could receive passes from his national teammate Murray instead.

“He probably got tired of me screwing up!” Jaimie laughed.

“He probably got tired of me screwing up!” Jaimie laughed.

Not long after John pulled Jaimie aside.

“He said, ‘You know, I’m only hard on you because you can be good. You’ve got potential.’ He pointed out somebody else and said, ‘Do you ever hear me yell at him?’ I nodded no. ‘Yeah, because he has no potential. He is who he is.’”

As harsh as it could be at times, words like that coming from an established star when you’re a young athlete just starting out were pure gold.

Soon others were seeing the same raw potential in Jaimie. Generally a point guard, he was a strong passer and ballhandler, as well as a tough defender for his size and classification. He looked up to Murray Brown and Chris Samis, both Class 1.5 players, who were key parts of the Canadian men’s wheelchair basketball team at the 1992 Paralympics in Barcelona (where Canada finished fifth overall) and weren’t just role players who set picks. Both were very talented ballhandlers and shooters at point guard and shooting guard.

“So that’s who I got to learn from here,” explained Jaimie. “In BC we had a reputation that our lower Class players had to handle the ball, had to do things, and not just set screens for a Class 4.0 player to take a shot. So, it was a great environment in that regard. I don’t know what I would have ended up like if I didn’t have that environment. I learned to handle the ball and not turn the ball over against some very high Class international players coming out to cause havoc.”

Within a couple of years since his start in the sport, Jaimie made BC’s provincial wheelchair basketball team in 1992. Just a couple of years after that, he was on the brink of making the national team. For the 1994 Gold Cup (now known as IWBF World Wheelchair Basketball Championship) in Edmonton, Jaimie was kept around to practice with the team leading up to and during the tournament as a way to gain a little experience at that level. By the next year, he was named to the national team and except for a couple short breaks he remained a cornerstone of the national program for the next 13 years.

Within a couple of years since his start in the sport, Jaimie made BC’s provincial wheelchair basketball team in 1992. Just a couple of years after that, he was on the brink of making the national team. For the 1994 Gold Cup (now known as IWBF World Wheelchair Basketball Championship) in Edmonton, Jaimie was kept around to practice with the team leading up to and during the tournament as a way to gain a little experience at that level. By the next year, he was named to the national team and except for a couple short breaks he remained a cornerstone of the national program for the next 13 years.

His first international trip when Jaimie made his debut with the national team came in a qualifying tournament in Buenos Aires, Argentina leading up to the 1996 Paralympics. Madonna happened to be in the city at the same time filming the movie Evita, which led to some funny moments.

“I remember being on a bus and we were all these very North American-looking white guys essentially. Sometimes people would gather around us because they thought we were part of Madonna’s entourage going around Buenos Aires at the time.”

On the court, Jaimie and his Canadian teammates played through 40-degree Celsius temperatures with high humidity (thankfully in an elevated open-air gymnasium, which allowed some air flow and relief) as Canada qualified for the 1996 Atlanta Paralympics.

In Atlanta, Canada ended up facing the US in the quarterfinals, a tough match-up that could have been a gold medal final. The Americans knocked off the Canadians on their way to a bronze medal, while Canada edged France 69-68 to take the fifth-place game. By that point Jaimie had established himself as Canada’s undisputed floor general, directing the team on the court or “moving the chess pieces around the board” as he later said. There was no better example than that fifth-place game against France where he played every minute as the game went to double overtime. It became typical of him to log heavy minutes and lead Canada forward.

“I was very fortunate. Didn’t spend a lot of time on the bench.”

“I was very fortunate. Didn’t spend a lot of time on the bench.”

Jaimie’s arrival on the men’s national team coincided with the emergence of several other now-legendary players as Canada was about to embark on an unprecedented decade of international dominance. Joining Jaimie around that time was fellow BC Sports Hall of Famer Richard Peter, as well as Manitoba’s Joey Johnston and Ontario’s Pat Anderson, the latter often cited as one of the sport’s all-time greatest players. Canada’s men had always been solid, but suddenly they were a rising international power with these young reinforcements.

At the 1998 World Cup in Sydney, Australia, Canada battled to a bronze medal impressively taking out the host Australians, the defending Paralympic gold medalists, in the bronze medal match. Jaimie was selected to one of the five spots on the tournament’s World All-Star Team, but when asked about it he modestly spoke of the team and his teammates.

“That was our coming out party,” summed up Jaimie. “We had Joey. We had Richard. And, of course, this Pat Anderson character who was quite young. All of a sudden there was this group of young kids coming together. We just started dominating after that.”

The Canadians were an emerging force, but still working through some growing pains. A dominant performance could be followed by one where Canada might be pushed around on the court. Canadian men’s national coach Mike Frogley, a former national team player himself, openly encouraged and challenged his players to “start pushing back” and not let them get outmatched physically. One particularly memorable speech from Frogley during a game where Canada found itself playing down to a weaker team’s level stuck in Jaimie’s mind as a key turning point.

The Canadians were an emerging force, but still working through some growing pains. A dominant performance could be followed by one where Canada might be pushed around on the court. Canadian men’s national coach Mike Frogley, a former national team player himself, openly encouraged and challenged his players to “start pushing back” and not let them get outmatched physically. One particularly memorable speech from Frogley during a game where Canada found itself playing down to a weaker team’s level stuck in Jaimie’s mind as a key turning point.

“He said, ‘It’s not your fault that they didn’t train as hard as you, didn’t put in as much time, that they’re not as good as you. It’s not your fault. You have to play your game. You don’t have to play down to their level.’ The implication was that as Canadians we were too nice. The Americans would hammer anybody they played, but we would rarely hammer the weaker teams. It worked. It was a message we needed to hear.”

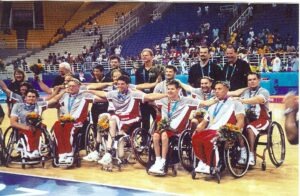

At the 2000 Paralympics in Sydney, Australia—the first ‘modern Paralympic Games’ with a true Athlete’s Village and other elements often taken for granted at the Olympics—the Canadian men’s wheelchair basketball team, led by Jaimie, Richard, Joey, and Pat absolutely dominated, winning every game decidedly. Canada breezed through the five round robin games outscoring the opposition 327 to 196. With over 15,000 fans in the stands for every game in the medal round, Canada just kept rolling, taking out Sweden 73-39 in the quarters, downing Great Britain 66-51 in the semis, and breezing by the Netherlands in the gold medal match 57-43 for Canada’s first-ever men’s Paralympic wheelchair basketball gold medal.

granted at the Olympics—the Canadian men’s wheelchair basketball team, led by Jaimie, Richard, Joey, and Pat absolutely dominated, winning every game decidedly. Canada breezed through the five round robin games outscoring the opposition 327 to 196. With over 15,000 fans in the stands for every game in the medal round, Canada just kept rolling, taking out Sweden 73-39 in the quarters, downing Great Britain 66-51 in the semis, and breezing by the Netherlands in the gold medal match 57-43 for Canada’s first-ever men’s Paralympic wheelchair basketball gold medal.

“The gold medal game was anti-climactic because it was halfway through the fourth quarter and we were in complete control. There was no crazy last second shot like Kawhi Leonard with the Raptors, but we did it! A bit of relief and a sense of accomplishment obviously. Those periods of time take you through the rest of your life in your career and other things. We were part of a machine that was very well-oiled, very well looked after at all levels. It wasn’t a fluke like Australia winning in 1996. It wasn’t unexpected. Canada should win this. It was pretty special. We were the best team in the world at this thing that all these people were trying to do.”

Two years later at the 2002 worlds in Kitakyushu, Japan, the Canadians went in as heavy favourites but were bounced by the US in overtime in the semifinals. The United States took the gold over Great Britain, while Canada edged the Australians for bronze. A solid result in any other year, but standards had been raised and it felt like a disappointment to Jaimie and his teammates.

“That fueled us for two years later in Athens.”

“That fueled us for two years later in Athens.”

There the Canadian men were the defending Paralympic champions and they blazed through the competition at the 2004 Games just as they had four years earlier. Canada once again didn’t lose a single game in the tournament, going 5-0 in the round robin (outscoring opponents 353-235) and then knocked off Japan and the Netherlands in the quarters and semis respectively. In the final they took down the Australians 70-53 for Canada’s—and Jaimie’s—second consecutive Paralympic gold medal.

Canada was on top of the wheelchair basketball world once again and a major reason for that was Jaimie, their starting point guard and co-captain for

much of his time on the national team. Not only was he their trusted floor general, but Jaimie also served as a voice for the players off the court, his teammates counting on him to represent them well with officials, coaching staff, opponents, and media. When asked to describe Jaimie, teammates and coaches offer him the highest praise.

“Pound for pound, one of the best and smartest players in the world,” said Canadian teammate Dave Durepos.

“A great leader both on and off the court,” added Richard Peter, a 2010 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “A good teammate, leader, researcher, and friend, always great to have in your corner.”

“Jaimie was a player whose local and international reputation was that of a tactical genius,” said Tim Frick, a 2017 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “He displayed excellent on-court ability in his tactical play, but more importantly off the court his creativity to develop new concepts and his ability to relay that information to teammates was unmatched. He was a popular teammate who led by example and always put the team first.”

“Jaimie brought to the national program a desire to be the best athlete he could be and not simply a role player,” said former Canadian national team Mike Frogley. “The result was a player that changed the way the game was played for future class 1’s. His level of play was so elevated that I chose to have him guard players of higher classification, something unprecedented for a player at his classification and, to this day, something that is not seen very often. The result of Jaimie being able to ‘guard up’ meant that it gave our Canadian Men’s team a match-up advantage elsewhere on the court. It was this defense that was the cornerstone of the success the Canadian team had over three gold medal games.”

Jaimie and his teammates had reached the pinnacle of the Paralympic Games twice, but the peak of success at the world championships had to that point eluded them. It remained something they all kept driving for and in 2006 in Amsterdam they finally reached their goal. Canada was by then a bit older and a little more mature and, as such, the coaching staff gave the players more autonomy and left them to their own devices knowing they could be trusted to perform when it mattered.

“I remember at that time Joey Johnston played for a professional German team that was sponsored by a brewery and his wife showed up with these crates of beer,” chuckled Jaimie. “So he set up his own ‘Joey’s Pub’ in our hotel room that we the veterans would pop into and partake.”

Firing on all cylinders, Canada defeated the US 59-41 in the gold medal match to claim the country’s first-ever world wheelchair basketball title.

Firing on all cylinders, Canada defeated the US 59-41 in the gold medal match to claim the country’s first-ever world wheelchair basketball title.

“We finally broke through and won gold at the worlds. That was a great tournament in Amsterdam. Just a great atmosphere.”

Canada would also play in other international tournaments each year with a good deal of success. Over the years, Jaimie helped the team to tournament wins in the Roosevelt Cup, Tournament for the Americas, and the Osaka Cup. He was selected the 2006 tournament MVP in the latter.

Tired from the grind of international competition and looking to pursue other interests, Jaimie took a year off in 2007, not even sure if he’d return to the national team. Ultimately, the lure of chasing three consecutive Paralympic gold medals drew him back into the Canadian fold for the 2008 Paralympics in Beijing.

Canada was again the favourite, but the gap between them and other chasing nations had closed. Jaimie and his Canadian teammates rolled through the round robin with a perfect 5-0 record before dispatching Israel in the quarterfinals and the always-tough Americans in the semi-finals. It set up another match-up with another archrival, the Australians in the gold medal match. Despite a game-high 22 points from Pat Anderson, the Aussies claimed gold with a 72-60 victory. Canada settled for silver, giving Jaimie his third Paralympic medal to go along with his earlier two golds. The fact that Jaimie started and played an integral role in three straight Paralympic gold medal games over eight years, winning two of them, is a startling accomplishment that very few athletes in any sport have on their resume.

“What makes his accomplishment so remarkable is the excellence that is required for an athlete to compete in three successive gold medal games,” summed up coach Frogley.

“What makes his accomplishment so remarkable is the excellence that is required for an athlete to compete in three successive gold medal games,” summed up coach Frogley.

It was quite the accomplishment to go out on. Jaimie retired from international play after the 2008 Paralympics.

“I had enough miles on my shoulders,” he said.

It was the right time for other reasons too. The national team was moving towards a model of centralizing all players in Toronto and Jaimie had never lived away from home in the Lower Mainland all his years on the national team to that point. Moving across the country just wasn’t that appealing to him with he and his wife Carrie Linegar expecting a baby at that time as well. First son Evan arrived in 2009 and their second son Rhys was born in 2013.

We’ve focused mostly thus far on Jaimie’s performances at the Paralympics and world championships, but at the same time he was also massively successful playing on the BC provincial team and his club teams. Even after retiring from the national team he continued playing with Team BC and his Douglas College club team until 2012 and won 13 national titles (eight with Team BC, five with Douglas College) over the course of his career, while being named to national tournament all-star team 11 times. He was also part of the 2008 BC Cable Cars that won the National Wheelchair Basketball Association Division 1 championship, one year after they had won the silver medal in the competition.

The other remarkable aspect to Jaimie’s story is what he doing off the court while travelling the world representing Canada. He somehow found the time in between games, practices, travel, and training to complete a Ph.D. in neuroscience at UBC and two post-doctoral fellowships. Dr. Borisoff also designed and invented the Elevation Wheelchair, which allows users to raise, lower, and change the angle of their seat themselves in order to reach objects or transfer to another chair.

The other remarkable aspect to Jaimie’s story is what he doing off the court while travelling the world representing Canada. He somehow found the time in between games, practices, travel, and training to complete a Ph.D. in neuroscience at UBC and two post-doctoral fellowships. Dr. Borisoff also designed and invented the Elevation Wheelchair, which allows users to raise, lower, and change the angle of their seat themselves in order to reach objects or transfer to another chair.

“I built it. I designed every single part, over 150 parts. I was so immersed in it at the time, I could see it in my head. Blow it up and look around it in my head and take it apart and see that bolt go in and that sort of thing. So many ridiculous details that does not come to me easily. I made something that other people use, so that was cool.”

He also founded a startup company to market and sell the Elevation Wheelchair to the public. The lives of countless people who use it daily have been improved immeasurably and this might be Jaimie’s proudest accomplishment over and above anything he accomplished on the court.

Since retiring fully from playing, Jaimie has served as a Canadian research chair in rehabilitation engineering design at BCIT and is the director of MAKE+ at BCIT.

Jaimie was honoured as the BC Wheelchair Sports Association Athlete of the Year twice (1998, 2006), the BC Wheelchair Basketball Society Male Athlete of the Year twice (2002, 2006), and the Wheelchair Basketball Canada Male Athlete of the Year once (2007). He was inducted into the BC Wheelchair Basketball Society Hall of Fame in 2020 and has been inducted into the Wheelchair Basketball Canada Hall of Fame three times as members of honoured teams.

He now adds induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame to that growing list.

“It means a lot. I feel lots of pride. Humbling a little bit too. It came out of the blue obviously. It was a really great call. I was like, ‘Really?! Wow! That’s cool.’”

As part of the Class of 2023, Jaimie Borisoff was formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Athlete category at the annual Induction Gala held June 1, 2023 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.