Lori Fung: An Olympic Dream Come True

October 31, 2022By Jason Beck

This article was supposed to start off much differently a week ago.

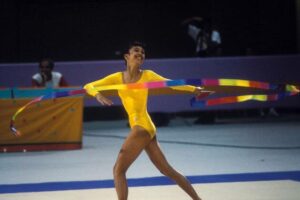

It was going to open with the fact October is Women’s History Month and that Lori Fung, Canada’s greatest rhythmic gymnast, was going to be emceeing the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s Class of 2023 Media Announcement this past week, so what better time to look back at her incredible story. All of these things are still true, but at that announcement on October 25th I witnessed something truly awe-inspiring. Something that changed this article for me and gave me a glimpse of the inner strength residing within an Olympic champion like Lori, the first-ever Olympic gold medalist in the sport of rhythmic gymnastics back in 1984 at the Los Angeles Olympics.

the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s Class of 2023 Media Announcement this past week, so what better time to look back at her incredible story. All of these things are still true, but at that announcement on October 25th I witnessed something truly awe-inspiring. Something that changed this article for me and gave me a glimpse of the inner strength residing within an Olympic champion like Lori, the first-ever Olympic gold medalist in the sport of rhythmic gymnastics back in 1984 at the Los Angeles Olympics.

Lori and I had a great interview about her career over the phone the previous week and I was excited to help prep her prior to emceeing on the 25th. When I went over to say hello when she arrived that morning at the Hall of Fame, she shared with me some tragic news. Her father, Dr. Edward Fung, had passed away a few days earlier while in the hospital. I was completely shocked and my first thought was ‘How are you even here today, Lori?’ That alone was amazing. As Lori shared that her dad would have wanted her to be here at the Hall today, I tried my best to be supportive knowing there was very little I could say or do to make things better for her.

As she almost grew tearful and thoughts of her father worked their way to the surface, she put a sudden stop to it and in that instant I saw first-hand the Olympic champion in Lori Fung. Just as if she was stepping out onto the floor to perform a difficult gymnastics routine in front of thousands, Lori quickly composed herself and focused on the task at hand. We went through the event script and I just had this feeling that she had this. She was going to be great.

And she was. Like she was as an international athlete, she was composed, strong, charismatic, and friendly. Any other average person wouldn’t have been able to function bearing that burden. Under the most difficult of circumstances, not a single person in BC Place’s Gate A concourse would have suspected the immense loss Lori was coping with. I’m sure somewhere Lori’s father was looking down and was very proud of his daughter that day.

It truly was one of the more amazing things I have witnessed in nearly two decades at the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Full stop. And it illustrated better than anything to me why Lori Fung is undeniably one of the greatest athletes in BC sport history: along with grace and beauty, that unique inner strength, mental toughness, and discipline that propelled her as an underdog western outsider to the top of her sport against all odds is still there. Her story is remarkable and it’s an honour to share it with you here. While you read, spare a thought or prayer for the Fung family at this difficult time.

It truly was one of the more amazing things I have witnessed in nearly two decades at the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Full stop. And it illustrated better than anything to me why Lori Fung is undeniably one of the greatest athletes in BC sport history: along with grace and beauty, that unique inner strength, mental toughness, and discipline that propelled her as an underdog western outsider to the top of her sport against all odds is still there. Her story is remarkable and it’s an honour to share it with you here. While you read, spare a thought or prayer for the Fung family at this difficult time.

Growing up in east Vancouver, Lori surprisingly didn’t play any organized sports when young, but there were signs of the artistic/athletic path she later forged.

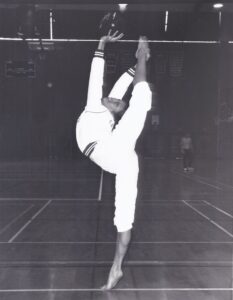

“I was energetic and I loved to perform,” she told Wendy Long in the 1995 book Celebrating Excellence. “I was always roller skating and bike riding and didn’t want to come in to eat dinner because it interrupted my play. I liked to roller skate under the street lamp of Eighth Avenue. I used to pretend I was performing. I’d make up routines on the road. Cars would wheel around the corner and I’d be doing my arabesque.”

The direction of Lori’s life changed in 1976 when like so many other young girls watching the Montreal Olympics on television, she saw the great Nadia Comăneci win five gymnastics medals including three gold and receive the first perfect 10 in Olympic gymnastics history for a flawless routine on the uneven bars. After that, everything became about gymnastics for Lori.

“Seeing Nadia win in 1976 sort of planted that seed of a dream in my heart,” Lori said in 2006 of this moment of inspiration. “I would say that was my biggest moment of like ‘Wow! I want to do that.’”

As would become a pattern in Lori’s life, the next piece of the puzzle just seemed to fall into place for her perfectly. One day not long after at Chief Maquinna Elementary, she saw a notice on the bulletin board about an after-school gymnastics club that was starting up.

“They had a little once-a-week artistic gymnastics program and I joined it,” she recalled. “I was so excited that I was doing this 45 minutes a week in gymnastics and I thought ‘Oh, this is my chance to go to the Olympics!’ Not realizing what it really took.”

Lori was already 13 years old and, although she didn’t know it, she was literally years behind girls her age from many eastern European nations behind the Iron Curtain where gymnastics was a major sport. In Canada, it barely registered on the sports landscape, but that didn’t matter to Lori. What she lacked in experience and opportunity, she more than made up in passion for gymnastics.

“One of the elementary teachers Penny Tonge said to my parents ‘She loves this so much that you should consider putting her in this new sport I’ve heard of called rhythmic gymnastics. Why don’t you enroll her?’ So I got enrolled and I was hooked. It went from zero to 250% at that point.”

She started in the beginner’s recreational program, but her coach Mall Vesik said maybe she could do some of the competitive program. This was now twice a week and it still wasn’t enough for Lori. It’s fair to say that no one could have loved rhythmic gymnastics more than she did as she became obsessed with the sport almost instantly.

“I was begging the coach to let me come to every class that she taught, just so I could practice on the side. I was going to the older ladies classes, the five-year-old beginner’s recreational classes, plus my provincial competitive classes. But I just wanted to do it all the time.”

Despite her relatively late start into the sport, it actually turned into something of an advantage for Lori later on against most of her competitors from eastern Europe who had all been involved in gymnastics from a much younger age.

Despite her relatively late start into the sport, it actually turned into something of an advantage for Lori later on against most of her competitors from eastern Europe who had all been involved in gymnastics from a much younger age.

“Being that crazy about the sport—when I say 250% committed I mean 250% and I loved it—but it was different for many of my competitors from eastern Europe. I remember an interview with a really good friend of mine from Bulgaria, Lilia Ignatova, at one point the world champion and considered one of the best in the world, where she said she does rhythmic gymnastics because she has to, but she said she wished she could do it like her good friend Lori Fung, who does it because she loves it. It was a job for her.”

Many of Lori’s competitors, worn down by years of grueling training, would lose the spark they had for their sport, whereas Lori’s passion seemed to burn brighter and brighter as she progressed and made up for lost time catching up to her contemporaries. The other remarkable thing about this young girl from east Van infatuated with all things gymnastics was an unusual unshakeable belief in herself from a very young age. Even though rhythmic gymnastics wasn’t even an Olympic sport yet, she somehow believed that one day she would be competing at the Olympics in it.

“I used to say to everyone, ‘Well, I’m going to the Olympics.’ Everyone would be like, ‘Oh my god, this girl is delusional. She doesn’t even do a sport that’s in the Olympics.’ But I was just convinced. My mom said I just drove them crazy because I’d be like, ‘I’m going to the Olympics. I’m going to win.’ I remember people saying, ‘Okay, you’re just a kid from east Vancouver, you’re not going to go to the Olympics, and you’re not going to win.’ I don’t know, my mom and dad often said I have a really stubborn streak, so when people would tell me something like that, I’d be like, ‘I’m going to show you!’”

If there was one thing Lori had in spades it was determination.

“I think that there was something that was born inside of me to work hard and I had never found it until gymnastics that you can work hard at something that you love so much.”

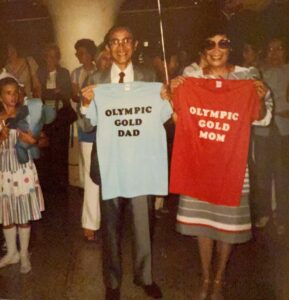

She also had the complete support of her parents, Ada and Edward, and her older sister Cheryl, who was Lori’s role model. Lori’s father, Dr. Fung, knew the value of participating in sports firsthand after serving as the cox of the UBC rowing crew in the early 1950s. He later served as president of the BC Rhythmic Sportive Gymnastic Federation and was vice-president of the national federation. Besides driving Lori to gyms all over Vancouver to practice, he and Ada volunteered their time at local gymnastics meets and helped fundraise for Lori’s club, Rhythmika, coached by Mall Vesik.

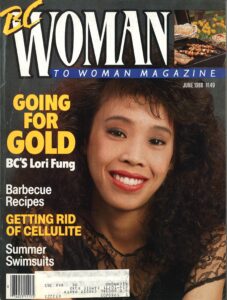

“We encouraged her through the various phases of competition,” Dr. Fung told Woman to Woman Magazine in 1988. “Lori had the drive and initiative to do it, we didn’t have to coax her. She would even insist on training when she had injuries.”

“My parents were not pushy at all,” said Lori. “They were not pushy sports parents. They were the most laid back and just ‘what you want to do, you need to do’ and they supported me 100%. And I mean I was in it like 250%. They actually used my training as a punishment if I was ever out of line. They would say, ‘Well, you can’t go to practice tomorrow.’ And that was just the worst punishment in the whole world! It kept me on the straight and narrow though, I’ll tell ya!”

It’s hard to imagine someone more committed to their sport.

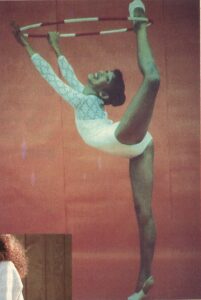

“I slept with my hoop,” chuckled Lori. “I slept with my apparatus. I carried that apparatus to school every day. In high school at Van Tech I would keep my hoop in the counselor’s office until lunch time. Then I would wolf down my lunch, quickly go down to the office, grab my hoop, and head to the gym. I would ask the basketball team if I could just use a little corner of the gym to practice, to throw my hoop around. That’s how dedicated I was.”

It even went farther than that. When it was announced in 1981 that rhythmic gymnastics would be added to the Olympic Games beginning in 1984, Lori said, “It was like all the stars fell into place for me.” Yes, the sport was now in the Olympics, but she still had to make it there and to do that she had to become the best in Canada. Lori went all in, as Vesik increased the intensity and volume of her training. Lori made the decision to do her final year of high school by correspondence so there was more time for training. It was one of many sacrifices she was more than willing to make to realize her dream.

“When you make the choice to become an elite athlete, it’s difficult because you give up a lot of things,” she explained. “In my mind, I gave up nothing. I was prepared to give up school and do school by correspondence. I was willing to give up going to my senior prom. I was willing to give up going to parties and growing up like a regular teenager. I could do all of those things after I had finished my gymnastics but I could only do gymnastics at that time.”

“When you make the choice to become an elite athlete, it’s difficult because you give up a lot of things,” she explained. “In my mind, I gave up nothing. I was prepared to give up school and do school by correspondence. I was willing to give up going to my senior prom. I was willing to give up going to parties and growing up like a regular teenager. I could do all of those things after I had finished my gymnastics but I could only do gymnastics at that time.”

Add it all up and it resulted in a remarkably rapid rise. Within a year of discovering the sport, Lori was already on a competitive team. Within two-and-a-half years, she was already going to national championships. Within four years, she was on the national team. Within seven years, she was at the Olympics. It was almost unheard of.

“Most people spend their entire life from age six to the age of 18 or 20 before they ever get a shot at the Olympics,” she said. “But I fast-tracked myself in a way that I think no one could understand.”

Lori began competing internationally for Canada in 1980. The following year, after finishing second in the All-Round at the Canadian trials, she earned a berth to the world championships in Munich, West Germany. There she saw the strength of the competition from behind the Iron Curtain as she finished 30th in the All-Round and 16th in the Rope event. She also became just the second Canadian ever to achieve a 9.0 average at a world competition, following Shirley Lehtinen who did so in 1977.

By 1982, Lori won her first of seven straight Canadian senior Grand National Championships. Invitations to compete in prestigious competitions around the world became common—Bulgaria, France, Japan, and New Zealand in 1982 alone. She was also beginning to occasionally creep into the top-20 when facing the best internationally. Sometimes even higher, such as a second-place finish in the All-Round at the Four Continents Championships that year and first in the clubs event—the first of four gold medals at these championships during her career.

By this time Lori was the top-ranked rhythmic gymnast in Canada, but in order to challenge the best in the world she needed to look beyond our borders. At times her coach Mall Vesik took a sabbatical from coaching and Lori would look for other coaches and athletes to train with while she was away. One of the first opportunities came when Lori was just 18. Why not learn from the best in the world at that time she thought? So Liliana Dimitrova, the Canadian national team coach in Toronto, phoned the Bulgarian national team asking if Lori could train with them. They agreed.

“So off I went by myself to Bulgaria to train for a month.”

Travelling alone to Bulgaria behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War was a pretty big trip for a young 18-year-old from east Vancouver. It was culture shock from the moment Lori’s plane touched down.

“I didn’t know any of the language. I was by myself. When I landed, I was in the terminal looking for my luggage and then when I got it, I was just standing there. I had no idea who was going to meet me or anything, having no contact numbers and of course no cell phones or anything. And I’ll never forget this man wearing dark glasses, a leather jacket, jeans, and cowboy boots walked up to me and said, ‘Kanada?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And he grabbed my suitcase and he beckoned me to follow him. I can’t believe I did this. I followed him and I got into a van with him. He spoke no English. I’m sitting in the van going, ‘I just got into a vehicle with a strange man in a foreign country, what is going to happen here?!’ As it turns out, his name was Ludmil Kotzev and he was the ballet master for the national team and they sent him to pick me up, but I just trusted.”

“I didn’t know any of the language. I was by myself. When I landed, I was in the terminal looking for my luggage and then when I got it, I was just standing there. I had no idea who was going to meet me or anything, having no contact numbers and of course no cell phones or anything. And I’ll never forget this man wearing dark glasses, a leather jacket, jeans, and cowboy boots walked up to me and said, ‘Kanada?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And he grabbed my suitcase and he beckoned me to follow him. I can’t believe I did this. I followed him and I got into a van with him. He spoke no English. I’m sitting in the van going, ‘I just got into a vehicle with a strange man in a foreign country, what is going to happen here?!’ As it turns out, his name was Ludmil Kotzev and he was the ballet master for the national team and they sent him to pick me up, but I just trusted.”

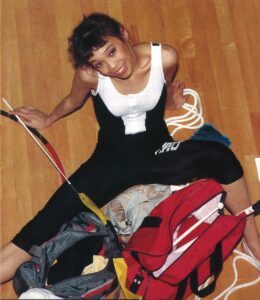

Training abroad and learning from some of the world’s best rhythmic coaches and athletes proved invaluable for Lori and only continued her rise in the sport internationally. After winning the All-Round at an invitational meet in Switzerland in 1983, she finished 23rd in the All-Round at the world championships in Strasbourg, France, the top-ranked North American in the field. The 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles and the Olympic debut for rhythmic gymnastics were next on the horizon, but despite being the top-ranked rhythmic gymnast in Canada, the Canadian Olympic Association remained non-committal about sending Lori or anyone to LA in rhythmic. Selectors had said she need to be in the top 25 in the world rankings in order to be selected, but now were saying the top 16. Determined to make it, Lori spent 1983 and the early part of 1984 competing in meets all over Europe and Asia in an effort to raise her world ranking and show she could compete with the very best.

“I did a lot of travelling that year,” she remembered. “I went to France, Poland, so many international competitions, sort of chasing the qualification criteria. I was number one in Canada but that wouldn’t guarantee a position on the Olympic team.”

A crucial decision was made in early 1984 to go to Romania and train with the national team there for six weeks. With most of the eastern bloc nations expected to boycott the Olympics as the west had done in 1980, the Romanians were expected to be the top rhythmic gymnastics nation in Los Angeles and favoured to take gold. Even though Lori could be competing against their top gymnasts like Doina Stăiculescu and Alina Drăgan, they allowed her to come and train.

“I wasn’t a favourite, so I guess they didn’t see me as a threat,” she explained. “But I went there and considered myself a sponge. I just watched and learned everything that I could. When I came home, I just trained like crazy with all my knowledge of going to Bulgaria, going to Romania and everything that I had up until the Olympics.”

“I wasn’t a favourite, so I guess they didn’t see me as a threat,” she explained. “But I went there and considered myself a sponge. I just watched and learned everything that I could. When I came home, I just trained like crazy with all my knowledge of going to Bulgaria, going to Romania and everything that I had up until the Olympics.”

Strong top-10 finishes at international competitions in Bulgaria, France, and Japan all contributed to raising Lori’s world ranking to ninth overall. Just a month before the Olympics, Lori was informed that she was on the Canadian Olympic team and going to Los Angeles.

It was almost unheard of for a Canadian gymnast to reach this level, especially in rhythmic, but surprisingly Lori’s profile in the sport seemed to be growing faster abroad than at home. Outside the local gymnastics community here, few were taking any notice.

“My sport and my accomplishments don’t carry much weight with the media in Vancouver,” she told the Winnipeg Free Press in June 1984. “I’ve really done very well this year in pretty tough competition. But the papers always say there isn’t room for any of it. Apparently, they’ve got their hands full with the Whitecaps and the Canucks and the Lions.”

Even Province columnist Jim Taylor commented on the lack of awareness of rhythmic gymnastics in BC in his own unique way: “Until the Olympics how many people outside the ring of competitors, parents, and close friends had heard about rhythmic gymnastics? How many wanted to know? Rhythmic gymnastics? Sounds like something you try for birth control.”

It wouldn’t be long before this all changed and Lori pushed Vancouver’s pro teams from the sports pages.

It wouldn’t be long before this all changed and Lori pushed Vancouver’s pro teams from the sports pages.

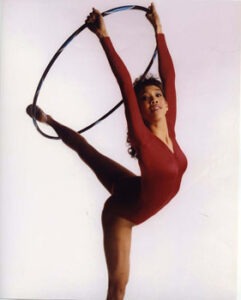

Prior to the Olympics, as Lori trained seven days a week often working on her routines in the early mornings at UBC’s War Memorial Gymnasium, she was never alone. There was always one person working with her and another key reason for her rise in the sport. At that time all the top rhythmic gymnasts in the world had their own piano player that they worked with who played the music that accompanied their routines on a grand piano in the corner of the floor in competitions. It meant that the athlete and pianist had to develop true chemistry as no two routines were ever the same. The athlete might throw the ball a little higher one time or delay a ribbon throw just slightly. It meant the pianist had to always be watching their athlete as they played, anticipating these slight variations and then occasionally slow down or speed up their playing to keep the routine in time with the music.

When Lori returned from Romania in early 1984, she decided she needed to have her own piano player. She was given a tape of music, which she loved, played by Donna Forward, a music major at Capilano College and the daughter of Dr. A.D. Forward, the chief surgeon at Vancouver General Hospital. Lori and Donna had met the summer before when on vacation at a dude ranch up in the Cariboo. Donna was working there as a horse wrangler and taught Lori how to ride. She was a terrific pianist but had never even heard of rhythmic gymnastics.

“I said to her, ‘Do you want to come to the gym and try?’” remembered Lori. “She did and it all worked out. Like I’m telling you, everything became perfect. It just all worked out.”

As they trained together often six hours a day and travelled all over the world to competitions, they gelled into the perfect team.

“The only regret I have is that there should have been two gold medals given out like in pairs ice skating events,” said Lori. “Because she was my teammate, my partner, and she was a very big part of why I won the gold medal.”

They worked on the music for routines together, with Donna helping Lori perfect much of the timing and spirit of each to make them unique.

“We were always looking for new music. She was a big fan of country and Jimmy Buffett, so part of my clubs routine music was Buffet’s ‘One Particular Harbour’. One year my rope routine was ‘Crocodile Rock’ by Elton John. But it was made for rhythmic.”

They quickly developed a special bond that went far beyond just gymnastics and piano. They became very close friends.

“Donna knows what I’m thinking before I even think it,” Lori told Woman to Woman Magazine in June 1988. “She’s not my pianist—I’m her gymnast!”

Donna’s natural sense of humour became the perfect release valve for the pressures of training and competition that often weighed down on Lori.

“I’d be at practice and I’d be absolutely exhausted,” recalled Lori. “My coach would be yelling at me from the side to do another routine. I would feel absolutely nauseous. I had just gotten off a plane and I’m expected to perform like a puppet. I would just be on my last legs thinking to myself I just can’t do this anymore. When I would get to that low point, Donna would duck behind the piano and put on this multi-coloured clown wig and start my routine. All I had to do was look over there and it would just brighten up my spirit and she would sort of get me through those times. There were a million things she used to do like that, that always lifted my spirits. That’s a huge thing because as an athlete you can’t always be 100% on the ball all the time. Sometimes you have down times and for those times Donna was there for me.”

“I’d be at practice and I’d be absolutely exhausted,” recalled Lori. “My coach would be yelling at me from the side to do another routine. I would feel absolutely nauseous. I had just gotten off a plane and I’m expected to perform like a puppet. I would just be on my last legs thinking to myself I just can’t do this anymore. When I would get to that low point, Donna would duck behind the piano and put on this multi-coloured clown wig and start my routine. All I had to do was look over there and it would just brighten up my spirit and she would sort of get me through those times. There were a million things she used to do like that, that always lifted my spirits. That’s a huge thing because as an athlete you can’t always be 100% on the ball all the time. Sometimes you have down times and for those times Donna was there for me.”

And Donna was there for Lori at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion, venue for rhythmic gymnastics at the 1984 Olympics. Already ranked in the world top-ten, with the eastern bloc boycott, Lori’s ranking moved up to number three, but not many were counting on her for a medal. Not even her family.

Lori’s parents and sister were in LA supporting her and they managed to get tickets for the preliminary round, but didn’t expect her to make the final, so they were thinking they’d visit Disneyland instead that day. When Lori qualified, they had to scramble to find tickets. Trying every other method possible without success, they stood on the sidewalk with a handwritten sign that read ‘Parents of Gymnast Need Tickets.’ Luckily they found someone willing to part with theirs and got in to witness Lori make history.

After the preliminary round, Lori stood tied for third behind the two favoured Romanians Doina Stăiculescu and Alina Drăgan. Just excited to be in medal contention, Lori called her mom Ada the night before the final.

“I said, ‘Oh mom, I wish it was over now because then I’d have a bronze medal.’ And she said, ‘Don’t you dare say that! You’ve been saying to us forever that you’re going to go to the Olympics and you’re going to win. You have a chance now! Just don’t settle.’”

Lori took those words to heart and on the day of the final she made a startling decision that few competitors would ever dare to make. Considering what was at stake and the risk involved, it may be one of the greatest gambles in Canadian Olympic history. And it showed just how confident Lori was in her ability to perform under pressure. At the last possible moment, Lori decided to change her ribbon routine, one that she had worked on perfecting for months.

And the reason why was not what you’d expect: the air conditioning in the Pauley Pavilion was wreaking havoc on the ribbon routines of all the competitors. Blasts of air from the overhead ducts were tangling up ribbons and throwing off the best in the world. Before the competition got underway, after seeing the conditions all competing nations put in a request to have the air conditioning turned off during the ribbon routines. But the organizers refused saying the computers used for the scoring system would overheat.

“So they basically said, ‘Deal with it. It’s the same for everybody. It’s not like it’s favouring one person or another,’” recalled Lori. “It was crazy. All the gymnasts in the back, we all just thought, ‘That’s it. All of our ribbon routines are going to be crap.’ So it would be really weird: everyone would be getting 9.7s, 9.8s, 9.9s in all their other routines and then your ribbon routine would be 9.0 or 9.1 because there were so many problems with the air conditioning.”

In the preliminary round, Lori’s ribbon routine scored a 9.2, which actually was one of the higher marks. Without telling anyone, not even her coach, Lori decided if she wanted to push the Romanians for gold, she needed to adapt her routine.

“I realized I was sitting in third place in the final and that it was a clean slate. I thought to myself, ‘Okay, everyone is just willing to accept a low score in their ribbon routine. Everybody. Maybe I should do something.’”

During the practice session just before the final, Lori noticed which way the air was flowing when she was working on her ribbon.

“So I put my whole routine to one side of the carpet where the ribbon was always out that way so it flowed out and it didn’t get tangled. If you put your ribbon in the other direction, the wind was so strong it was blowing the ribbon into itself and then everyone was getting knots, tangled, it was on the body.”

One mistake and the gold and silver were out of the question. It could even be enough to bump her off the podium entirely. While others were again finding their ribbon tangled up in their legs or around their neck and given deductions from the judges, Lori threw down a clean routine. You can actually see her ribbon fluttering in the wind at the beginning of this video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L22L6yK6nMg

“From a technical point of view my routine was terrible because it was all on one side of the floor. Whenever I threw the ribbon in that direction, I just threw it gently because I knew the wind would help me. When I had to throw the ribbon in the other direction, against the wind, I threw it really hard. I did a routine that probably wasn’t the greatest as far as what it looked like, but it was clean so I ended up going high. I think the judges were thinking, ‘Wow, a clean routine! This was a good one, we’ve got to reward it!’”

She ended up scoring a personal best 9.8 for the ribbon, the highest of anyone in the competition. With personal best scores in the other three disciplines as well—9.8 for clubs, 9.75 for ball, and 9.7 for hoop—it put her into the lead. Those that she had been chasing, most notably the overwhelming favourite Doina Stăiculescu, had struggled once again with their ribbons. Stăiculescu scored 9.25 for instance, allowing Lori to make up a lot of ground.

“If I would have won a silver medal I would have been on cloud nine, but she [Doina] was devastated,” Lori said. “Because she was the favourite to win. Everybody knew she was going to win, like hands-down. In the rotation I was following her, just by chance almost every time. She was doing her routine and I was on deck and then she’d be coming off and I’d be going on. I remember high fiving her and saying, ‘Awesome Doina! You’re doing so well! You’re going to win!’ Not realizing that her last routine was a disaster.”

Lori had been slowly creeping up on her throughout the final but didn’t know if it was enough. In fact, Lori wasn’t even out on the floor at the end.

“I was in the change room after finishing my last routine,” she recalled. “I didn’t look at any scores. I didn’t want to look. I just went straight to the dressing room. I’m packing up my bag and I’m so proud of myself that I had a really good competition. Didn’t really think about where I was.

“Then a friend of mine from the US team came flying into the room saying, ‘Lori! Lori! You did it!’ I’m sitting there and said, ‘Did it? Did what?’ I was thinking I kept my bronze medal position. And she said, ‘You won!’ And then I went out to the floor and it was like crazy. All of sudden there was a security guard on me because I was tagged for doping testing. Everything was going crazy. And I didn’t know what was happening. It was just like a whirlwind and then it remained a whirlwind for years after that.”

“Then a friend of mine from the US team came flying into the room saying, ‘Lori! Lori! You did it!’ I’m sitting there and said, ‘Did it? Did what?’ I was thinking I kept my bronze medal position. And she said, ‘You won!’ And then I went out to the floor and it was like crazy. All of sudden there was a security guard on me because I was tagged for doping testing. Everything was going crazy. And I didn’t know what was happening. It was just like a whirlwind and then it remained a whirlwind for years after that.”

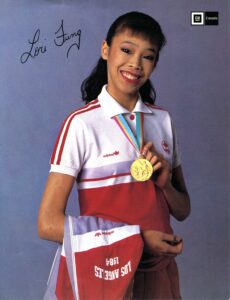

Lori Fung, the young girl from east Vancouver who told everyone she was going to go to the Olympics before her sport was even contested there, was now the first-ever Olympic champion in rhythmic gymnastics. She ended up edging Stăiculescu by just five hundredths of a point to take gold—57.950 to 57.900. Not considered a threat by the Romanians just six months earlier when allowing her to train with them, Lori ended up snatching up the gold medal out from under them.

As she stood up on the podium as Canada’s tenth and final gold medalist of the Los Angeles Olympics, tears streamed down her cheeks.

“I can’t believe this,” Donna Forward told the Vancouver Sun’s Mike Beamish as Lori stood on the podium. “A year ago I didn’t know this sport existed. Now Lori is the Olympic champion.”

“It’s like a dream come true,” Lori told the Province’s Mike Gasher. “I wasn’t expecting a medal.”

“It was the smallest dream I ever had,” she told United Press Canada. “I couldn’t believe it. I never really expected it. I was just hoping to do well.”

Even just a few months earlier, who would have thought it possible for a gymnast from Canada, an admitted minnow among the big fish of world gymnastics, to pull off such an historic performance as this? And suddenly, Lori and rhythmic gymnastics seemed to be everywhere.

It started immediately after the competition with dozens of interviews with media from all over the world. Then the celebration continued back home as soon as she touched down at Vancouver International Airport. Hundreds turned out to welcome the returning Canadian athletes and most were there for Lori, so many the RCMP had to be called in for crowd control. When she made it through customs, she was greeted by a massive roar from the gathered crowd, many of whom held bouquets of flowers for her. Balloons floated in the background bearing the message ‘We Love You Lori!”

“I don’t believe it,” she said to the crowd. When her father Edward called out and got her attention, the tears flowed. Tears of joy.

“It’s a joyous moment,” Dr. Fung said. “She’s given a lot of young people something to shoot for.”

“It feels like a smile is frozen on my face,” she told supporters. “I sometimes think I’m going to wake up and still have to compete in the finals.”

After being all but ignored before the Olympics, Lori suddenly was one of the most recognizable people in BC, if not Canada, making countless appearances and receiving armfuls of prestigious awards.

The City of Vancouver presented her with a civic award, while the Vancouver Museum named her a patron with a ten-year membership and gave her a silver bracelet bearing an Indigenous design. She was flown to Toronto where she and other Canadian medal winners were honoured at CNE Place by Prime Minister John Turner. She attended the 1984 Grey Cup representing Canada’s Olympic athletes. She met Elton John when he was town for a concert and they had their picture taken—Elton wearing Lori’s gold medal and Lori holding his latest gold record for the album Breaking Hearts. She was asked to perform a ball routine to ‘Ave Maria’ at BC Place Stadium during Pope John Paul II’s papal visit. During Expo ’86, she performed a lot with David Foster including for Prince Charles and Princess Diana. She was even asked to perform in a big ABC television tour called Symphony of Sport with the great Nadia Comăneci, who started all of this for Lori so many years before.

The City of Vancouver presented her with a civic award, while the Vancouver Museum named her a patron with a ten-year membership and gave her a silver bracelet bearing an Indigenous design. She was flown to Toronto where she and other Canadian medal winners were honoured at CNE Place by Prime Minister John Turner. She attended the 1984 Grey Cup representing Canada’s Olympic athletes. She met Elton John when he was town for a concert and they had their picture taken—Elton wearing Lori’s gold medal and Lori holding his latest gold record for the album Breaking Hearts. She was asked to perform a ball routine to ‘Ave Maria’ at BC Place Stadium during Pope John Paul II’s papal visit. During Expo ’86, she performed a lot with David Foster including for Prince Charles and Princess Diana. She was even asked to perform in a big ABC television tour called Symphony of Sport with the great Nadia Comăneci, who started all of this for Lori so many years before.

She also was in demand for modelling, endorsing products, appearing in commercials and did some acting. People would stop her on the street constantly and ask for her autograph.

“I think it’s great because every time someone recognizes me, they remember rhythmic gymnastics and the sport really needs all that recognition.”

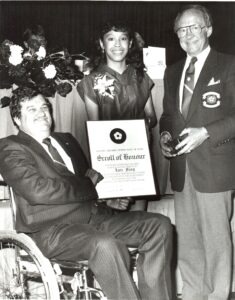

And then there were the awards. In 1985 Lori was named to the Order of Canada. In 1990, she was awarded the Order of BC. In 2004, she was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame.

Before all of those, she was first inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame while still an active athlete. As an Olympic gold medalist, the standard three-year waiting period after retirement was waived for her.

“I appreciate it now more than when there was so much happening back then,” she said. “Meaning, if I could relive it all again, I would really appreciate it more at the time, but I am appreciating it now. It was just a little bit too much at that time for a young girl from east Vancouver to be thrown into all of that so quickly. I wasn’t prepared for it. It means so much to me now.”

Lori would continue competing internationally for another four years under the direction of coach Liliana Dimitrova as the top rhythmic gymnast in the western world. At the 1985 World Rhythmic Gymnastics Championships in Valladolid, Spain, she finished 9th overall in the Individual All-Around, as well as 6th in the Individual Clubs and 8th in the Individual Ball. No other gymnast beyond the Iron Curtain was even close to her.

She went into 1988 hoping to defend her Olympic title at the Seoul Olympics as the top-ranked rhythmic gymnast in the western world, but broke her heel in training just before the Games and was forced to retire.

Lori then turned to coaching, something she had already started even while still competing herself. Two of the more prominent athletes she coached included Camille Martens, who competed for Canada at the 1996 Olympics, and Nerissa Mo, a six-time national champion in various age groups. Lori currently owns Elite Gymnastics Club based out of Burnaby, serving as the club’s mentor with various coaches working under her direction.

Lori then turned to coaching, something she had already started even while still competing herself. Two of the more prominent athletes she coached included Camille Martens, who competed for Canada at the 1996 Olympics, and Nerissa Mo, a six-time national champion in various age groups. Lori currently owns Elite Gymnastics Club based out of Burnaby, serving as the club’s mentor with various coaches working under her direction.

The sport has grown immensely in BC since the early days when Lori was just starting out and a lot of the credit has to go to Lori herself. Where once there were no clubs at all in the Vancouver area, now there are more than ten. Prophetically, just prior to the 1984 Olympics, Lori said this to the Province’s Terry Bell:

“I think after LA things will boom [for rhythmic gymnastics]. It’s our turn. It will be just like what the ’72 and ’76 Olympics did for gymnastics. Fathers and mothers will want their daughters in this sport—kids can really relate to the kind of things we do. It’s exciting, fun, and requires skill.”

Lori was right on target, although even she couldn’t have imagined she herself would be the driving force behind the sport’s growth.

Retirement also afforded Lori the chance to raise a family of three boys with husband Dean Methorst. She calls her family her proudest accomplishment.

And occasionally Lori is pulled back into the performance spotlight. Maybe the most memorable was as an aerial ballerina in the 2004 movie Catwoman staring Halle Berry and Benjamin Bratt.

“I just got my residual cheque for this year!” she laughed. “It’s the gift that keeps on giving!”

Nearly forty years later, it still seems almost unbelievable for a Canadian to break through the eastern European dominance of rhythmic gymnastics and achieve international success like Lori did. Every once in a while even she has to remind people and it can lead to some humourous situations, such as the time she was hiring a ballet master for her club about six or seven years ago. The man Lori was interviewing came very highly recommended and met her at the gym.

“I know rhythmic gymnastics, I’m from Romania and my very good friend won a silver medal at the Olympics in rhythmic gymnastics. Doina, she has been over to my house for dinners,” he said.

“I was just standing there looking at him and it was just one of those awkward moments: ‘Do I tell him?’” Lori chuckled. “Then when I hired him, he was working with our group of gymnasts and I said to him, ‘I’m sorry, you threw me off, but I know Doina too. I just didn’t know what to say when you said that because I’m the one who won the gold medal over Doina.’ He turned to me and said, ‘You’re the one!’ We had a good laugh about that.”

“I was just standing there looking at him and it was just one of those awkward moments: ‘Do I tell him?’” Lori chuckled. “Then when I hired him, he was working with our group of gymnasts and I said to him, ‘I’m sorry, you threw me off, but I know Doina too. I just didn’t know what to say when you said that because I’m the one who won the gold medal over Doina.’ He turned to me and said, ‘You’re the one!’ We had a good laugh about that.”

Again, it just shows how unlikely Lori’s rise truly was. It also goes to show that you can be growing up in the wilderness of certain sports, but if you want it enough, you can make your dreams come true. Lori certainly did.

“When I was growing up as a normal kid who didn’t do any organized sports in east Vancouver, I thought you had to be born into a special kind of family or born into some special kind of place to be able to win a gold medal at the Olympics like a Nadia Comăneci,” she said. “Part of me thought you had to be Russian or Romanian before you could go to the Olympics. Now going out to elementary schools in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland, I talk to children and tell them that I had a dream and I was just exactly like them, just started a sport after school once a week and that dream built into something. I think that is a huge thing when I tell children that it can be for them too, that it’s okay to dream and for a lot of them that dream might come true.”