Wynn Gmitroski: Born To Coach – 2023 Inductee Spotlight

September 29, 2023By Jason Beck

In August when the World Athletics Championships in Budapest, Hungary took place, I couldn’t help thinking about Wynn Gmitroski.

One reason was because Wynn had coached athletes at 16 world championships (including indoor) during his career. The other was because of how well Canada performed winning the second most gold medals (four) behind only the United States and six medals total. Much of the groundwork for the success Athletics Canada has enjoyed over the past decade leading up to this new milestone was laid in the ten-to-fifteen-year period prior to that by individuals like Wynn and a handful of others. In that time Wynn established himself as one of Canada’s top athletics coaches over the past forty years. Some people are just born to coach and Wynn is one of those. When you trace the arc of his involvement in sport, the signs of a future hall of fame coaching career are everywhere from an early age.

Born in Selkirk, Manitoba in 1957, Wynn’s earliest sport memory comes from just after he learned to walk. His father put him on ice skates on an outdoor rink.

“I was almost trying to run on them,” Wynn chuckled in a Zoom interview from his second home in Phoenix, Arizona earlier this year. That was a fitting start because there was a lot more running to come for him.

The Gmitroski family home was on a five-acre rural piece of property surrounded by farms about an hour from Winnipeg. The acreage was the perfect testing ground for young Wynn who had an imagination and appetite for sport from the beginning.

The Gmitroski family home was on a five-acre rural piece of property surrounded by farms about an hour from Winnipeg. The acreage was the perfect testing ground for young Wynn who had an imagination and appetite for sport from the beginning.

“With the property we created all kinds of sports fields of our own,” he recalled. “We had a backstop for baseball, football goalposts. I even made a little three-hole golf course and had a driving range on it into two acres of field that I plowed up. I had a long jump pit, high jump pit. All types of things like that. Then I cut the grass around the driving range and had a 400m track. That was all by the time I was in junior high.”

One day he was reading a comic book and at the back of it he saw an ad for the Joe Weider bodybuilding program. He slipped a five-dollar bill into an envelope and sent away for it. A few weeks later a package of calisthenics workouts arrived in the mail for him.

“It got me going I think by the time of my eighth birthday,” he said. “I was amazed within a year or two how much it helped me in a lot of the sports I was doing. Just getting stronger and more coordinated. I learned at a very young age if I actually trained or prepared for something I got better. So there was more motivation to do that. I’m not really sure where it came from. It was just a spontaneous thing that happened.”

If there is such a thing as a coaching gene, Wynn was born with it. Even before coaching others, he was coaching himself. By elementary school, he was already planning his own training sessions.

“In Grade 3 we had a book of the month club,” he explained. “I remember buying this one book on swimming and diving and in the back it had how to make your own barbell set. I showed my dad and he said I could do it myself. He gave me the materials: two flour tins, a piece of reinforcing steel, poured some concrete and set it into the tins and I had a twenty pound barbell. That was my first weight training experience.”

One of the first people other than himself that he coached was his younger brother Sheldan, now one of Canada’s top throwing coaches based out of Victoria.

“He was one of the people I experimented on,” laughed Wynn. “When I would be practicing my pitching, he would be catching. Or helping me measure out the long jump.”

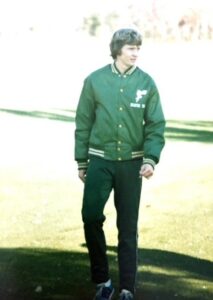

Years later Wynn coached Sheldan as one of his earliest middle-distance runners. But before that Wynn was still a runner himself too, competing in mostly the sprints and jumps in high school in Beausejour and later focusing on middle distance while attending Bemidji State University in northern Minnesota.

“It still amazes me that I went into track and field coming from a place where it gets down to minus -30 or -40 in the winter,” he said.

His high school coach, Robert Grant, was a key early influence, as was his university coach, Robert Eudiekis. By his third year of university, Eudiekis was telling Wynn he should be a coach.

His high school coach, Robert Grant, was a key early influence, as was his university coach, Robert Eudiekis. By his third year of university, Eudiekis was telling Wynn he should be a coach.

“I didn’t have a clue what that was,” Wynn said. “He kept encouraging me. It wasn’t until years later I figured out what that was. After university, track got in my blood and just never left.”

In his fourth year of university as one of the co-captains of the Bemidji State track team, Wynn was planning workouts with Eudiekis. At the same time, while Wynn was competing he continually was getting injured and sick. Some of his initial interest in coaching and in physio came from trying to find answers to his own issues, but also how he could prevent them from happening to other people.

After graduating from university, Wynn went back to work at his high school in Manitoba as a PE instructor. Robert Grant, his old coach, was still there and they built the school’s track program back up from half a dozen kids to over 75 athletes including some provincial champions by the end of his second year.

“It really motivated me to work with these kids that were so keen to achieve,” he said. “It was exciting.”

From there, Wynn went to the University of Oregon to attend grad school in sport science. While there, another key influence, Alex Gardiner from Athletics Canada, was encouraging Wynn to focus on coaching middle-distance runners. When Wynn finished up at Oregon, he went back to Manitoba and the first thing he did was attend the national junior championships in Winnipeg. Walking into the stadium, the first person Wynn bumped into was Alex and Bill McDonald, coach of the Winnipeg Raiders track club that Wynn had run with.

“First thing they say to me is, ‘We hear you’re coaching next year,’ Wynn recalled. “I didn’t hear that. All I wanted to do was run and maybe find some work. They had this all orchestrated. Bill was retiring and they wanted me to take over his position. That’s where my senior coaching started. From there, it really became a huge passion.”

As Wynn became more and more involved in coaching with the Raiders and later at the provincial and national level, he got to know Dr. Doug Clement, well known here in BC as one of Canada’s leading track coaches and an early sports medicine pioneer. Wynn often called up Doug to ask him coaching or medical questions.

“He was always so kind to be patient and to talk to me about these things.”

One time in the mid-1980s after both men attended nationals in Ottawa they shared a cab to the airport.

One time in the mid-1980s after both men attended nationals in Ottawa they shared a cab to the airport.

“I remember asking Doug, ‘How do you afford to coach when you’re not paid for it?’” Wynn recalled. “He just said, ‘You need to find a profession that will support your habit, because it’s expensive.’ It was right around that time that I was thinking about the physio thing and I thought I really have to put something together with what he’s talking about. So I built my practice with the flexibility so that I could travel and I could support myself.”

Wynn subsequently went back to the University of Manitoba and graduated in 1988 as a physiotherapist. Not only could he coach elite athletes, now he knew how to treat them and prevent injuries. It was a game-changing combination that took his coaching to a new level.

When Wynn registered as a physiotherapist, he did so in both Manitoba and BC so that he could practice in both provinces. It was a timely decision as right around then physiotherapy had been granted primary billing status in BC. Wynn had also begun flying out to Victoria to work and treat Brent Fougner’s University of Victoria athletes.

That wasn’t his first introduction to BC though. Way back in the summer of 1973, Wynn’s family had come out to visit his mother’s cousin in Victoria and they camped for a month at Goldstream Park.

“The weather was just so perfect from July into August. And at that point my brother and I said, ‘We’re coming back here to live.’ I didn’t want to come home. I tried to stay for another month but my dad insisted I had some work to do before I went back to school. I always knew that I was coming back to BC.”

So in 1990, Wynn made the move out west, settling in Victoria and soon after established the Cedar Hill Sports Therapy Clinic that he operated for nearly 25 years. He knew the move west could only help his athletes.

“Realistically, from a coaching perspective, training at 30-below in the winter through two or three feet of snow is not an advantage,” he laughed. “Victoria was the right place at the time and the weather was amazing from what we were used to in the winter. Many of the athletes I worked with in Manitoba came out.”

One of the first who followed Wynn west was none other than Angela Chalmers. Slowly others followed and local athletes joined Wynn’s training group, but Angela was in a class all her own, a rising international star.

One of the first who followed Wynn west was none other than Angela Chalmers. Slowly others followed and local athletes joined Wynn’s training group, but Angela was in a class all her own, a rising international star.

Wynn had actually begun coaching her back in Manitoba. Angela was attending Northern Arizona University when Wynn became Manitoba’s provincial coach for endurance events. Angela’s university coach, Ron Mann, used Wynn as their point person in Canada to support her.

“They didn’t know anybody built into the Athletics Canada system to support her at nationals,” Wynn explained. “So each year when she would go to nationals, Angela would connect with me. Then we developed some trust over a few years of that.”

After graduating from university, Angela asked Wynn to help her preparations leading up to the 1988 Seoul Olympics. She based her training out of Winnipeg and Wynn lived just 800m from the track there.

“So she’d go out to workouts and I’d go out and time her leading up to her departure to Seoul.”

In her first Olympics, Angela made the final in the 3000m finishing 14th and 17th overall in the 1500m, both very respectable performances. After the Games, Angela asked Wynn to develop training programs for her. Two years later, she won gold in both the 1500m and 3000m at the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland, New Zealand.

“That was probably the turning point [for me],” he said. “That changed my life as a coach.”

Wynn remained Angela’s coach for the rest of her remarkable career. This included Angela winning bronze in the 3000m at the 1992 Olympics, an absolutely unbelievable result he said.

“You get these endorphin highs when something happens when you plan for it for years and then it actually happens or it happens better than you thought,” he marveled. “A lot of times you’re so in the process, you forget about what’s happening until it actually happens. The first time that really happened, just completely mind-blowing, was in 1992 with Angela pulling off the bronze medal.”

But she didn’t stop there. Angela shouldered immense pressure as she captured gold again in the 3000m at the 1994 Commonwealth Games in their adopted hometown of Victoria. Then she went on to perform unbelievably in Europe the rest of that season winning the Grand Prix Final.

The best result of Angela’s career may have actually been possible at the 1996 Olympics, but two weeks before the Canadian Olympic trials Angela’s season and career came to an end due to a stress fracture suffered in training. Wynn called it the most heartbreaking moment of his career. Angela was a favourite to medal in both the 5000m and 1500m at the Olympics that year. Wynn went to Atlanta as one of Canada’s coaches for the Games and watched these races from the stands without Angela knowing she would have been a force in both of them.

“Watching the 5000m and knowing she was ready to win that,” he said shaking his head. “She was doing workouts prior that were breaking the world record. That was one of the hardest times. But it goes with the territory. If you don’t put it out there and risk things, you don’t achieve.”

Coaching an international star like Angela helped put Wynn’s name on the map and people began taking notice of him during an otherwise dismal era for Canadian athletics in the post-1988 fallout from the Ben Johnson doping scandal.

“Being a Canadian on the international scene, you were the bottom of the barrel,” he said of that time. “You were scum. It was hard to get a hotel room. It was hard to get in the meet unless you were world class. I was just lucky in that my first steps on the international scene were in 1989 and it happened to be coaching Angela then. It was hard to get her into competitions. But for the average elite international, it was mission impossible to try to get into competitions and so expensive. It was pretty tough through the better part of the 1990s.”

Early on in Victoria, the group of athletes Wynn coached were a mix of elite and recreational. Angela was still living part of the year in Arizona at that time and it was through coaching her there that Wynn made a key discovery that elevated the training of all of his athletes from that point on.

“She was my connection to Flagstaff and altitude training,” he said. “But it wasn’t until after Angela had retired that I really started to access that more.”

In the mid-to-late 1990s, Wynn became the first coach bringing a handful of athletes down to Flagstaff for high altitude training.

“It was a nice quite little place where you could go and relax,” he said of that time. “Now there’s so many athletes down there, they have no place to train. Back then, it was just the university track. Now they have four or five tracks in Flagstaff and they’re overrun. There are so many internationals and Americans that want to train there all the time. It’s become a real challenge.”

Wynn was one of the first to tap into the fact that very few elite athletes in longer middle distance and distance events have success internationally if they’re not training at altitude. Probably 90% of all international medalists are. To keep pace with the best, you have to be doing altitude training. So Wynn and his athletes often left their training base in Victoria and headed south for a camp in Arizona. In 2008, they made it an annual part of their training cycle. Many of his athletes were growing tired of the constant rain and cold training through the winter in Victoria. They decided to move down to Phoenix for a change of scenery. On yet another sunny, warm day, Wynn and his athletes were lounging on the infield grass after a training session when one turned to him and said, “Why don’t we do this all the time?”

“I didn’t have a good answer for that!” he laughed. Later that day, he and his athletes bought a house in Phoenix, which Wynn still owns to this day. “This became our training base.”

From 2008 until 2017, Wynn’s group trained in Phoenix every year for several months. When they returned to Victoria, they trained at UVIC. The roster of athletes working with him became impressive over the years. Well known Canadian internationals like Nate Brennan (1500m), Matt Hughes (steeplechase), Zach Whitmarsh (800m), and Bruce Deacon (marathon). His best-known athletes after Angela were likely Gary Reed and Diane Cummins.

From 2008 until 2017, Wynn’s group trained in Phoenix every year for several months. When they returned to Victoria, they trained at UVIC. The roster of athletes working with him became impressive over the years. Well known Canadian internationals like Nate Brennan (1500m), Matt Hughes (steeplechase), Zach Whitmarsh (800m), and Bruce Deacon (marathon). His best-known athletes after Angela were likely Gary Reed and Diane Cummins.

Gary won a silver medal in the 800m at the 2007 world championships in Osaka, Japan, a mark for Canadian men in this ultra-competitive event that wasn’t bettered until just this past August when Marco Arop took gold in the 800.

“Gary just chipped away, chipped away,” Wynn described. “He was so unbelievably committed. And you could just see how hungry he was. He had that street fighter mentality that you need, especially for the men’s 800m which is one of the deepest events there is. You could see him progressing. When he put it together in 2007 at the world championships and got the silver medal, missing the gold by just one one-hundredth of a second, that was a mind-blowing situation.”

Diane twice finished in the top-10 in the 800m at the world championships (5th in 2001; 6th in 2003) and won a Pan American Games gold medal in 2007

and three Commonwealth Games medals (one silver, two bronzes) during her career. That first world championship result in 2001 though, in front of a home Canadian crowd in Edmonton, stands out for Wynn.

“Coming from 78th in the world to make the final in the women’s 800m and run a personal best by four seconds over a month period,” he said with a sense of awe. “That was a real high. Then she just became a whole other level of athlete after that.”

There were many standouts, but Wynn’s stable of athletes ran deep. One year around 2004 he was coaching four of the top five Canadian women in the 800m. In 2012 he coached six of the top eight Canadians in the men’s 800m. Not all were from BC, some from Ontario, Quebec, and other provinces. But to have these clusters of top elite athletes in one event is pretty remarkable. Clearly Wynn’s methods and process worked.

“Well, it builds on itself,” he said. “The key is having the support. Having things lined up between the national and provincial bodies and the finances. But also having the human resources available.”

Before the national sports bodies began to put their support teams together behind their elite athletes, in the early 1990s it was just something Wynn did on his own, relying on his friends to help with his athletes within their specialization.

Before the national sports bodies began to put their support teams together behind their elite athletes, in the early 1990s it was just something Wynn did on his own, relying on his friends to help with his athletes within their specialization.

“They just happened to be people that I connected with that were PhD’s or MD’s or ND’s or physios. They mentored me or supported me. Especially when I got to Victoria, I just looked at who was the best source of information and the highest level in their area. So I would go to people like Istvan Balyi and talk to him about long-term development and yearly planning. Or Howie Wenger, the physiologist at UVIC at the time. We would get together regularly and do brainstorming sessions with other coaches and athletes. Then just throw out an idea and spend an hour or two talking about that. Everybody thrived on it. It was just spontaneous. We built out of that and it was just supporting each other.”

When coaching his athletes, Wynn tried to approach each differently, doing an individual assessment of their needs and then modifying the best way possible to achieve success.

“There was no cookie-cutter mold. Different people thrive off of different things, so what do you tweak?”

And there was no great secret to his coaching success.

“The biggest thing was contact time and honesty. Then the loyalty that goes with it, the connection that’s involved. I always believed that when it came down to the final phase, three weeks prior to a major championship, I have to be there with the athlete every day. And I’ve got to see how they’re responding to tweak anything and help them make decisions. And really protect them and de-stress them as much as possible. So they don’t need to think. They just need to ‘do.’ My biggest thing was I want to prepare myself as best I can as an individual so I’m not somebody’s excuse for underachieving.”

That almost never occurred. Over Wynn’s career, he trained 19 athletes who were at one time or another either ranked in the top-10 in the world in their respective events or finished in the top-10 in a major international championship like the Olympics or the worlds. He also coached athletes to 15 national records, four Commonwealth Games medals, two Pan American Games medals, and one Olympic medal. Those are the biggest highlights but there are dozens of others.

“People that made finals and broke records along the way that were all great experiences,” he said.

For three decades Wynn was a constant presence at major international meets and championships all over the world, coaching Canadian athletes at seven Olympics, 16 world championships (including indoor), and five Commonwealth Games. It made for a bit of a nomadic lifestyle for much of those 30 years, only home for two or three summers in that time, and when away in Europe, Asia, or elsewhere often living out of a backpack.

For three decades Wynn was a constant presence at major international meets and championships all over the world, coaching Canadian athletes at seven Olympics, 16 world championships (including indoor), and five Commonwealth Games. It made for a bit of a nomadic lifestyle for much of those 30 years, only home for two or three summers in that time, and when away in Europe, Asia, or elsewhere often living out of a backpack.

Wynn’s success in track and field meant teams and organizations far outside Canada and even outside the sport approached him often out of the blue to work with their athletes. He consulted with such widely diverse organizations as the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers, Cirque du Soleil, Athletics Australia, British Athletics, the Royal Spanish Athletics Federation, even a month in Libya working with their national soccer federation. He was offered the head physio position and middle-distance coach at Qatar’s national institute of sport but turned that down. Other times he was asked to present to various regional, national, or international bodies such as the North American, Central American and Caribbean Athletic Association (NACAC). All told, Wynn worked and traveled to over 60 countries through his hands-on coaching career, which he began to gradually slow down in 2017 until retiring completely in 2022. He could never ever have imagined the way his career evolved when starting out building that little 400m track on his family’s property back in rural Manitoba.

“When I look back on it now, that’s probably the biggest surprise. Coming out of where I came from and then ending up sitting looking out a window in Arizona at the blue sky and sunshine, which is the end result of all of this. Because if it wasn’t for the coaching, I wouldn’t have even thought about coming here.”

Besides his home in Phoenix, Wynn continues to live part of the year north of Parksville, moving there recently after thirty years in Victoria.

He hasn’t left coaching behind completely though. During Covid he began hosting virtual sessions for athletes—from Olympians to 80-year-olds—essentially on self-care: how to stretch, how to do soft tissue work, how to activate and strengthen, for instance. He recorded over fifty 90-min sessions and decided to launch his own website which went live in the spring. You can find all of this, plus material specifically on coaching available on a subscription basis here:http://wynngmitroski.com

“This website is going to be my career work,” he summed up proudly.

Another life-changing discovery for Wynn also took place during Covid. He reconnected online with a cousin back in Manitoba and learned their great-grandmother was Indigenous meaning Wynn and his brother Sheldan also have Indigenous heritage. It was a shocking discovery as Wynn’s connection to that part of his family had long since disappeared when his mother died when he was just 16 years old. Wynn subsequently applied and received his Metis status in both Manitoba and BC.

Another life-changing discovery for Wynn also took place during Covid. He reconnected online with a cousin back in Manitoba and learned their great-grandmother was Indigenous meaning Wynn and his brother Sheldan also have Indigenous heritage. It was a shocking discovery as Wynn’s connection to that part of his family had long since disappeared when his mother died when he was just 16 years old. Wynn subsequently applied and received his Metis status in both Manitoba and BC.

“It’s been an interesting journey. A lot of learning and going back seven-to-eight generations on that side of the family tree that we knew nothing about.”

Through this process he also discovered that his grandfather on his mother’s side was of Sámi heritage growing up in a little village that bordered Sweden and Finland in what was formerly known as Lapland.

“He always used to tell me stories about how he used to herd reindeer, so this really put that piece together and this is thirty years after he’s passed away that we discovered this.”

Along with 2020 inductee Gino Odjick, it means Wynn’s story will be the latest addition to the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s Indigenous Sport Gallery in the near future.

Wynn’s career has been honoured in several ways in recent years. In 2007, he was named Athletics Canada’s ‘Outstanding Coach of the Year.’ In 2019 he was inducted into both the Greater Victoria Sports Hall of Fame and the Bemidji State Athletics Hall of Fame. But Wynn’s proudest accomplishment goes beyond awards or inductions.

“The consistency to hang in as long as I did to work with as many as I did,” he said. “But looking back on it, seeing the success some of these people have had in life and being contacted by them years later. To see how well they are doing in life now and to see that they’re happy along the way. That’s the biggest thing because everything else is so fleeting. You can see someone win a medal and that’s amazing. You got your day in the sun, but a week later that’s gone. It’s a memory in your head but not too many others and life goes on.”

“The consistency to hang in as long as I did to work with as many as I did,” he said. “But looking back on it, seeing the success some of these people have had in life and being contacted by them years later. To see how well they are doing in life now and to see that they’re happy along the way. That’s the biggest thing because everything else is so fleeting. You can see someone win a medal and that’s amazing. You got your day in the sun, but a week later that’s gone. It’s a memory in your head but not too many others and life goes on.”

Regardless, his induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame was another career milestone.

“I was surprised. These are not things that you think about. It’s almost surreal. It’s just such an honour when I look at the people [on the wall in the Hall of Champions] and see these names and think, ‘Do I really deserve to be here with these people?’ You just go a little numb with it all. But I’m extremely grateful. In the end it’s comparing apples and oranges across the board with so many things. I just think back to all the people that supported me along the way to make this successful. There’s just so many. You can never plan these things. These things happen because of choices you make on a day-to-day basis and just keeping your nose to the grind and doing your thing. It’s a by-product of everything, but it’s an amazing one.”

As part of the Class of 2023, Wynn Gmitroski was formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Builder-Coach category at the annual Induction Gala held June 1, 2023 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.