Peter Bentley: The Sportsman – An Athletic Tribute

September 30, 2021By Jason Beck

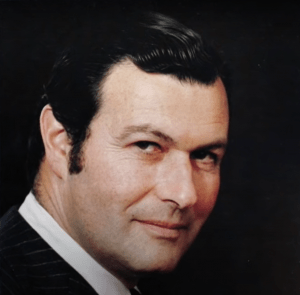

In an 18-month period that’s already taken from us two other giants of BC Sports Hall of Fame history in Norm Fieldgate and Jack Farley, we lost another pillar of our organization earlier this month in Mr. Peter Bentley. He passed away at the age of 91 on September 6th.

Mr. Bentley, as we all called him at the Hall of Fame out of great respect, was an outstanding supporter of the BC Sports Hall of Fame for decades. He still stands as one of the longest-serving trustees in our organization’s history, joining the board in 1969 and only stepping off in 1993, 24 years later. He served a term as the chair of the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 1974-75 and more recently sat on the Hall’s Foundation Board as well. When the Hall was raising funds to build a new facility at BC Place, Mr. Bentley brought Canfor on as the very first sponsor, funding the 1930s Decade Gallery. A few years later when the Hall’s new construction faced a significant financial shortfall, he was one of the first to step up again with a $100,000 donation as part of the ‘Finish Line Team.’ Later Mr. Bentley was named an Honourary Trustee, a title bestowed on a rare prestigious few whose contributions have gone over and above the exceptional. His son Michael continued the Bentley family support of the BC Sports Hall of Fame, himself recently completing over a decade of service on the Hall’s board of trustees.

Mr. Bentley even once saved the BC Sports Hall of Fame from eviction from the PNE over a dispute involving a light bulb by calling on the premier to intervene. You didn’t just misread that. It has to be one of the most remarkable stories I’ve ever heard in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s history.

It happened around 1977 or 1978. The BC Sports Hall of Fame was located then in the BC Building on the PNE grounds. Mr. Bentley was no longer the Hall’s chair by that time, but still heavily involved in the organization. One day fiery PNE president Erwin Swangard called Bentley and threatened to evict the Hall of Fame off PNE property because a Hall of Fame staff member had changed a light bulb in the facility. That was the PNE’s responsibility claimed Swangard. Bentley went out to meet with Swangard at his office and learned the light bulb in question was actually from inside one of the Hall’s own display cases.

It happened around 1977 or 1978. The BC Sports Hall of Fame was located then in the BC Building on the PNE grounds. Mr. Bentley was no longer the Hall’s chair by that time, but still heavily involved in the organization. One day fiery PNE president Erwin Swangard called Bentley and threatened to evict the Hall of Fame off PNE property because a Hall of Fame staff member had changed a light bulb in the facility. That was the PNE’s responsibility claimed Swangard. Bentley went out to meet with Swangard at his office and learned the light bulb in question was actually from inside one of the Hall’s own display cases.

“Look Erwin,” Bentley said firmly. “The building lights are your responsibility, but the cases lighting is ours, so don’t threaten me.”

Swangard refused to back down.

“Well, I don’t want any union trouble and I’m going to have you kicked out.”

Bentley calmly leaned over Swangard’s desk and picked up his phone.

“I called Premier Bill Bennett,” recalled Mr. Bentley. “I knew he was a great fan of the Hall of Fame, as was his father W.A.C., former BC premier. I also played a lot of bridge with Bill and knew him well. I said, ‘Mr. Premier, I’m in Erwin Swangard’s office and he’s threatening to kick us out. Could you straighten him out because we changed a light bulb in one of our cases and he figures that’s not legal.’”

Hearing this, Swangard lost it and yelled, “Give me the phone!” So Bentley calmly passed it to him. Swangard could only listen sheepishly as Premier Bennett laid down the law.

“Don’t you ever threaten to kick the Hall of Fame out or I’ll close the entire PNE down!”

Upon delivering this line, Mr. Bentley paused for effect before finishing his story with a wide grin.

“That was the end of that!”

***

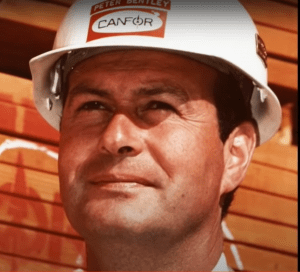

Mr. Peter Bentley was best known for his remarkable career in business. He elevated Canfor–started from scratch as a small furniture company known as Pacific Veneer by his father Poldi in 1938 when the Bentley family arrived in Vancouver–from a very large forestry operation into an international forestry giant. In the thirty years Mr. Bentley guided Canfor’s direction, he took the company from an already highly successful enterprise of $780 million a year in annual sales to one that generated over  $5 billion annually. He sat on the boards of many nationally significant companies including Shell Canada and the Bank of Montreal. He was also a devoted philanthropist who gave generously to numerous causes and organizations from the Vancouver General Hospital Foundation, which he founded and has now raised over a billion dollars for patients, to the Canadian Council of Chief Executives, Vancouver Police Department Foundation, and the Vancouver Art Gallery.

$5 billion annually. He sat on the boards of many nationally significant companies including Shell Canada and the Bank of Montreal. He was also a devoted philanthropist who gave generously to numerous causes and organizations from the Vancouver General Hospital Foundation, which he founded and has now raised over a billion dollars for patients, to the Canadian Council of Chief Executives, Vancouver Police Department Foundation, and the Vancouver Art Gallery.

“I like to give back to everything,” Mr. Bentley said simply in October 2018, when I had the opportunity to interview him in person at his office in downtown Vancouver, still putting in workdays at the age of 88 then.

The most surprising thing that came out of this 90-minute conversation was how much of a true sportsman Mr. Bentley was in every sense of that word. Perhaps overshadowed by his heady business accomplishments, I think many—myself included—didn’t realize how great of a multi-sport athlete Mr. Bentley had been in his day. How he not only had used his business contacts and financial means to improve and grow the BC and Canadian sports scene, but felt he had an obligation to do so given the privilege he had been lucky enough to enjoy and benefit from. And how he had followed many sports as a lifelong fan like any other person.

***

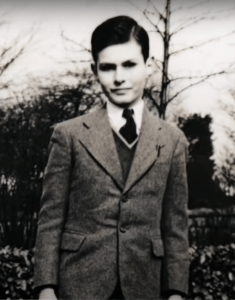

Sensing the impending conflict in Europe that would become World War II, when the Bentley family left Vienna, Austria and arrived in Canada in 1938, young Peter spoke German, Czech (“because I had a Czech governess”), and French, but no English. It was at St. George’s High School in Vancouver that Peter began learning English helped by many of the sports he began playing for the first time here. He played rugby, cricket, basketball, tennis, soccer, boxing, ran cross country, and captained the hockey team. His interest in sports, and you could argue a good deal of his natural ability, came from his parents, who had both been excellent athletes in their day back in Austria. His mother Antoinette was a world champion dressage rider, who likely would have medaled at the Olympics if women had been given the opportunity to compete in equestrian at the Games at this time. As it was, she regularly beat all of Austria’s male Olympic equestrian competitors in other competitions. Peter’s father Poldi had played right wing on the Austrian national field hockey team and was a first alternate on Austria’s Davis Cup team. He also played ice hockey growing up and through hockey became friends with members of the Molson family in Montreal. The Bentleys and Molsons remained close thereafter and served as a key connection later on when Peter used the family friendship to help bring Vancouver an NHL franchise.

both been excellent athletes in their day back in Austria. His mother Antoinette was a world champion dressage rider, who likely would have medaled at the Olympics if women had been given the opportunity to compete in equestrian at the Games at this time. As it was, she regularly beat all of Austria’s male Olympic equestrian competitors in other competitions. Peter’s father Poldi had played right wing on the Austrian national field hockey team and was a first alternate on Austria’s Davis Cup team. He also played ice hockey growing up and through hockey became friends with members of the Molson family in Montreal. The Bentleys and Molsons remained close thereafter and served as a key connection later on when Peter used the family friendship to help bring Vancouver an NHL franchise.

On the ice young Peter was a solid right winger who occasionally also put in shifts on defense. For some reason his parents didn’t want him playing junior hockey in Vancouver, perhaps afraid he might get hurt, so Peter kept it a secret.

“Whenever I had a game, I would tell them I was going skating,” he laughed years later.

You’ve got to give him credit. Technically he wasn’t lying.

Later he played in the Vancouver Commercial League with Pacific Veneer’s company team in New Westminster. They played out of Queens Park Arena with weekly Sunday night battles against teams from Alaska Pine, Finning Tractor, and, of course, the New West Salmonbellies.

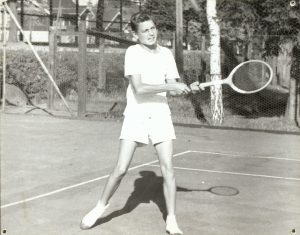

But out of all the sports young Peter tried, at first it was tennis that he excelled most. By the early 1940s, he was already one of the top junior players in the province, making the finals of the BC junior championship, but falling to another top young player named Lorne Main, who went on to have a remarkable tennis career and earned his own place in the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

But out of all the sports young Peter tried, at first it was tennis that he excelled most. By the early 1940s, he was already one of the top junior players in the province, making the finals of the BC junior championship, but falling to another top young player named Lorne Main, who went on to have a remarkable tennis career and earned his own place in the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

“I used to beat all the other top juniors all the time, but I never beat Lorne,” remembered Mr. Bentley. In a roundabout way you can make the argument that it was Lorne Main who caused Peter to become such a great golfer.

After losing to Main in the BC championship, Peter went down to Seattle where he played in the Pacific Northwest junior championships. In the semifinals he beat the California junior champion and number one seed in the tournament, but in the final Peter fell once again to the rising star and fellow Vancouverite Main. When he returned home and shared the news that he’d again come second to Main, the amazing fact two Canadian juniors featured in an American championship final held little weight with Peter’s father: “Look, if you lose to a guy that hits the ball with both hands from both sides because he’s so weak, I better get you a membership at a golf club so you can take up something you might get better at.”

On the surface it might sound harsh, but Mr. Bentley chuckled while recounting this memory as it led to his lifelong love with the game of golf. His father got him a membership at Marine Drive Golf Club. Hans Swinton, who had played against Peter’s father in tournaments back in Vienna, sponsored Peter. When they first began playing, Hans would give Peter a stroke a hole except the par-3’s to keep it close. Within a year, Peter could beat him straight up and had taken his spot on the UBC golf team.

According to long-time UBC Athletics historian Fred Hume, Peter lettered in golf three times at UBC. Beginning in 1948, he and lifelong friend Doug Bajus led UBC to the US Pacific Northwest Inter Collegiate Conference golf championship. The following year Bentley and Bajus again led UBC to the conference championship, this time in the US Evergreen Conference.

Most today have forgotten how great a golfer Peter Bentley was in his prime. It helped early on that his father was a solid player and that he took lessons from local stars Freddie Wood and the revered Stan Leonard. You couldn’t have asked for two better local players to learn from in the 1940s. As a golfer, Peter wasn’t the biggest driver off the tee, but as he related he “kept the ball in play” and relied on excellent irons and strong putting to become one the best amateur players in BC in the early 1950s often overshadowed by other great amateurs of the day like Bill Mawhinney, John Johnston, and Walter McElroy, who later were all inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame themselves.

For two years, from 1951 to 1952, Peter never shot a round over par at either Marine Drive or Capilano Golf and Country Club, where he kept memberships. It’s quite likely he would have been a regular on the BC Willingdon Cup team at that time except his father wouldn’t allow him to play in it, reasoning that their family could afford to send Peter to the Canadian Amateur each year instead and he would be taking a spot away from someone on the Willingdon Cup team who would be subsidized to go.

“He didn’t quite understand the significance of what it meant to make a Willingdon Cup,” said Mr. Bentley flatly.

“He didn’t quite understand the significance of what it meant to make a Willingdon Cup,” said Mr. Bentley flatly.

As it was, he was selected to play for Canada four times internationally at the senior amateur level, playing against the US three times and once against Great Britain. He won 17 club championships over the course of his life, the first coming in 1951 at Capilano and the last remarkably 47 years later in 1998 at Thunderbird Country Club in Palm Springs. He served as the non-playing captain of BC’s Willingdon Cup team in 1969. He also accumulated likely the most aces over his lifetime of any BC Sports Hall of Famer: nine hole-in-ones in total. Four came at Capilano, three at Marine Drive, one at University Golf Club at UBC, and one at Thunderbird.

One of his aces at Marine came as part of what he considers the best round he ever played, a sizzling 64 to win a special tournament of nine hand-selected top amateurs from BC. Mr. Bentley’s eyes lit up recounting the round in detail off the top of his head:

“I was three-under after five and my Dad was pretty keen. He was watching and he came up on the sixth tee and said, ‘You better hit a wood. Everybody is short.’ It was a par-3 and no way would I hit a wood because I didn’t want to go out of bounds. Then I hit a 3-iron and I sunk it. That put me five-under after six and then I birdied seven and eight. That day I was seven-under after eight holes, double-bogeyed nine, and then on the back nine I had 18 putts, hit both par-5’s in two and had a 33 coming home. I shot 64 and won the tournament by five strokes.”

Another round Peter recalled amongst his greatest came at Capilano when he was just 21 years old in a match-play tournament. He was scheduled to play the US Public Links champion in an early round but the American golfer showed up late for their pairing’s tee time. Rather than allow him to default, Peter had the starter let another pairing go ahead, but when the guy showed up he didn’t say thank-you for Peter’s sporting gesture. When they began their round the American asked him, “Where ya from, kid?”

“Right here,” Peter replied.

“I came 1500 miles to play a local hacker,” mused the American out loud.

Naturally, Peter was quite upset by that. He directed his anger towards his game and proceeded to play the first 14 holes in 8-under-par and beat ‘the jerk’—as Peter described him—5-and-4. When it came to the traditional post-match handshake, Peter didn’t put his hand out but instead said, “I’m sorry you didn’t get anyone better to play with” and left him standing there on the green.

After stepping back from active amateur play in 1953, Peter later served as president of the BC Golf Association from 1964-65 and as a governor of the Royal Canadian Golf Association from 1964-76. For ten of those years he served as chairman of the Canadian Open committee and including one year when he chaired the 1966 Canadian Open tournament held at Vancouver’s Shaughnessy Golf and Country Club—the last time the Canadian Open PGA event would be held in BC for nearly 40 years. Peter played a huge role in the 1960s elevating the stature of the Canadian Open until it was widely considered ‘the fifth Major’ of the PGA Tour.

One of the most unique aspects of Mr. Bentley’s career as an athlete is how he competed successfully in such widely disparate sports as hockey, tennis, golf, trap shooting, and auto racing. He took up trap shooting in 1954 when a back injury prevented him from golfing. He learned to shoot from his father, who was a good shooter himself, winning the prestigious Monte Carlo pigeon shoot one year. Peter proved he could hit the target as well, finishing third at the Canadian Olympic trials in 1956. Canada only sent the top two finishers to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics (where Saskatchewan’s George Genereux won gold) and Peter served as first alternate.

One of the most unique aspects of Mr. Bentley’s career as an athlete is how he competed successfully in such widely disparate sports as hockey, tennis, golf, trap shooting, and auto racing. He took up trap shooting in 1954 when a back injury prevented him from golfing. He learned to shoot from his father, who was a good shooter himself, winning the prestigious Monte Carlo pigeon shoot one year. Peter proved he could hit the target as well, finishing third at the Canadian Olympic trials in 1956. Canada only sent the top two finishers to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics (where Saskatchewan’s George Genereux won gold) and Peter served as first alternate.

“I just took it up and got lucky one day, which just happened to be the championship,” he recalled. “But I never went back.”

From 1954-59 Peter raced cars all over the Pacific Northwest. He loved fast cars and travelling at speed. He recalled racing a Jaguar XK 120 on the runway of the Abbotsford Airport. Later he switched to a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL roadster with the characteristic ‘gullwing’ doors that swung open upwards and remembered racing at the opening weekend of the Westwood Racing Circuit in Coquitlam.

“On the back straight at Westwood I could get up to 160 mph, which was the car’s top speed,” he grinned.

***

Although most of Peter’s participation in sports as an athlete was more limited after the 1950s as he focused on family and business, he remained active in the Vancouver sports scene in other ways. The most prominent was ultimately bringing an NHL franchise to Vancouver, only the third in Canada. Considering how prominent the Canucks have become to sport in BC over the past 50 years, it’s a massive accomplishment and Peter’s role is often overlooked. Many Canuck and even NHL histories gloss over the details and simply describe the ill-fated Tom Scallen as the Canucks original owner with the assumption that he brought the franchise to town, which is actually not true. Scallen was a last-minute replacement found by the NHL, who were scrambling to find the expansion Canucks an owner after the Canucks original ownership group led by Peter abruptly departed due to the NHL unexpectedly introducing new rules to limit the Canucks ability to field a competitive team.

It’s a tale of early Canucks NHL history that rarely gets told. Here’s how it went down according to Mr. Bentley who related the details to me in 2018.

For years, the Bentley family had season tickets for both Vancouver and New Westminster’s Western Hockey League teams and in 1962 they looked to become more involved. Through the Bentley family’s long friendship with the Molson family who owned the Montreal Canadiens, Peter worked out a tentative agreement with the Canadiens that could have proven a remarkable deal for hockey in Vancouver. If the Bentleys could secure ownership of the WHL Canucks, the Canadiens promised to send out future Hockey Hall of Famer Ken Reardon to serve as the Canucks playing coach and the club agreed to share players in the Montreal system with Vancouver, including every second pick of prospects. In the days prior to the NHL’s annual Entry Draft, the Canadiens were stockpiled with top prospects unlike any other team.

“That would have given us a helluva team here,” said Mr. Bentley.

Montreal also agreed to support any future Vancouver bids for an NHL expansion team. With that tentative agreement in hand, Peter then made an offer to buy the Canucks from the PNE and appeared to have that locked up.

“We thought it was a done deal.”

That is, until the Bentley offer was shared with former New Westminster and Vancouver mayor Fred Hume, who was also looking to get back into ownership of a WHL team after owning the New Westminster Royals from 1950-59. Hume submitted an identical offer to the Bentley’s except he offered the PNE one percent more share of the gate.

That is, until the Bentley offer was shared with former New Westminster and Vancouver mayor Fred Hume, who was also looking to get back into ownership of a WHL team after owning the New Westminster Royals from 1950-59. Hume submitted an identical offer to the Bentley’s except he offered the PNE one percent more share of the gate.

“They didn’t change anything else. They didn’t even write it up!” Mr. Bentley recalled, still sounding flabbergasted decades later.

The PNE went back to Peter with the Hume offer trying to leverage a better offer from him. Annoyed by the PNE’s tactics, Peter refused to change his offer and the PNE went with Hume’s, unknowingly losing out on a generation of spectacular Canadiens prospects electrifying Vancouver hockey fans in the process.

***

Despite the setback, Peter refused to give up on bringing the NHL to Vancouver though. When the NHL looked to expand for the 1967-68 season, a Vancouver bid was submitted by a group led by Cyrus McLean (chairman of BC Telephone Company), Coley Hall (owner of several Vancouver sports teams including the WHL Canucks), and legendary broadcaster Foster Hewitt. It was an ill-prepared application that lacked any kind of financial plan and focused more on the backgrounds of the individuals involved.

“My children, who were teenagers at the time, would have done a better job of it than they did,” remarked Mr. Bentley.

Although there was a great deal of shock and consternation when Vancouver was passed over in favour of six American cities in the first round of NHL expansion, knowing this background now it doesn’t seem so surprising. Initially, Peter looked into purchasing either the Oakland Seals or Pittsburgh Penguins and moving either of the expansion franchises to Vancouver, but there were complications in both situations and neither opportunity came to anything.

When the NHL moved to expand by two more teams for the 1970-71 season, Peter decided to pursue the expansion route instead. First he put together an impressive group of individuals that was strong both from business and sport perspectives. Besides himself, the group included his father Poldi and his uncle John Prentice from Canfor, Vancouver business leader Ron Cliff and Ron’s father-in-law Fred Brown, John Davidson, Frank McMahon (whose horse Majestic Prince would win two jewels of the Triple Crown in 1969), and Max Bell (owner of Canada’s largest newspaper syndicate). They also invited McLean, Hall, and Hewitt from the original Vancouver bid to join their group. Peter then asked the NHL if they could see the previous unsuccessful Vancouver application “so that we could learn from it.” To illustrate the significance of the sport in Vancouver, he hired a Vancouver company to produce a history of Vancouver hockey brochure dating back to when the Millionaires won the Stanley Cup in 1915. They emphasized how the team would play out of the newly-built Pacific Coliseum. And to show they were serious about building a competitive team, Peter worked with Coley Hall to purchase the entire roster of the AHL’s Rochester Americans from the Toronto Maple Leafs, who were in dire financial straits, for a cool $1 million to bolster the existing WHL Canucks. The Canucks instantly became championship contenders and won the WHL’s Lester Patrick Cup in both 1968-69 and 1969-70. Peter also visited all 12 NHL cities and met the owner of each team to introduce them to the Vancouver bid. It proved a highly effective tactic.

“We got 11 supporting votes,” recalled Mr Bentley. “Toronto voted against us because they figured they owned the TV market for all the west if there was no western team in the league.”

“We got 11 supporting votes,” recalled Mr Bentley. “Toronto voted against us because they figured they owned the TV market for all the west if there was no western team in the league.”

But trouble soon blew in. Peter arrived at a September 1969 NHL board of governors meeting and to his shock on the agenda was the idea of instituting a reverse draft for that one year only, which would take players away from Vancouver and distribute them to other teams around the league. Because of the Canucks recent success in the WHL with the players purchased from Rochester, the NHL felt the expansion team would be too strong. As this was being discussed and decided upon at the meeting, Peter stood up and spoke his piece.

“Gentlemen, I’m sorry,” he began. “My group’s objective was to get Vancouver into the big league. We’ve achieved that. We don’t have an ego trip like some of you guys that sit at this table. But if we are in, we want a good team and we’re going to work towards trying to win as much as we can. If you take these players, you better find yourselves a new owner.”

The other owners around the table suggested that Peter might want to speak with his colleagues before making this decision.

“No, I speak for everyone,” he said. “We’re like-minded in wanting to build a winner and being in the big league. If you won’t allow us to do that, to hell with you.”

He told those in the room that they needed to find someone else to own the team if these were the games the NHL wanted to play. And just like that, “I got up and I walked out,” he recalled. With just a year before what was to be Vancouver’s inaugural NHL season, the team was suddenly without an owner, an embarrassing turn of events for the league. That was when the NHL scrambled to save face and brought in Tom Scallen, the chairman of Minnesota medical insurance company Medicor and owner of the Ice Follies, as a replacement. Despite Toronto’s reluctance to share a piece of the Canadian market with Vancouver, in December 1969 Buffalo and Vancouver were announced as new NHL expansion franchises, a truly momentous landmark for sport in BC. Scallen was introduced as the Vancouver franchise’s owner, agreeing to pay the NHL a $6 million fee for the right to join the league.

Early warning signs of the financial mess Scallen would soon create appeared as early as when Bentley’s group transferred over ownership control of the new Vancouver franchise to Scallen.

“The bank said don’t sign anything until you have cashed his cheque and the bank has accepted it,” Mr. Bentley remembered. “It was that scary.”

McMahon and McLean stayed on the board of the new club for continuity. Peter bought a few shares as a minority owner just to show support.

“But when I got the prospectus, I saw there was some phony numbers and mistakes in it,” he said. “So I phoned their lawyer, who we also used, and he hung up on me. I knew it was wrong.”

“But when I got the prospectus, I saw there was some phony numbers and mistakes in it,” he said. “So I phoned their lawyer, who we also used, and he hung up on me. I knew it was wrong.”

Scallen was later convicted of theft and issuing a false prospectus. He served nine months in prison.

“He was a nice enough guy,” said Mr. Bentley. “He didn’t mean any harm. He just couldn’t afford it [and had to fudge the numbers]. His only asset was Peggy Fleming [the world champion figure skater] and the Ice Follies.”

Many observers later said the Bentley group backed out because of the $6 million expansion cost, but according to Mr. Bentley that wasn’t the issue. It was the lack of good faith and honesty shown by the NHL that turned his group away. These weren’t just high-minded ideals that could serve as a convenient excuse. When I asked Mr. Bentley what was his greatest life lesson he had learned, he said simply: “Openness, integrity, and sportsmanship are always important in everything.”

It’s interesting to speculate how the Canucks early history in the NHL could have turned out so differently if Peter’s original ownership group had the opportunity to guide the team. Regardless, you can’t deny him the fact that he helped Vancouver get a place in the world’s greatest hockey league.

***

As we neared the end of our conversation, I asked Mr. Bentley about his 1999 induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame, just the ninth individual honoured with the W.A.C. Bennett Award, the Hall’s highest honour. He said simply, “I was very honoured to be inducted.”

His proudest accomplishment was something much more significant though.

“I’m proudest of my family: all five of my children, my 15 grandchildren, all of whom are contributing to society. And we now have two great-grandchildren and another on the way,” he said. “I’m proud of all of my family.”