Gene Kiniski: ‘Canada’s Greatest Athlete’ – 2021 Inductee Spotlight

May 2, 2022By Jason Beck

If ever there was going to be a first professional wrestler inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame, it had to be Gene Kiniski.

It had to be.

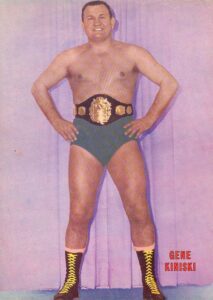

Canada’s Greatest Athlete.

Big Thunder.

National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) Heavyweight Champion for three years at a time in pre-WWF/WWE/WCW days when the NWA title represented the best professional wrestler in the world.

The face of the Vancouver-based nationally broadcast All-Star Wrestling weekly television show filmed out of BCTV’s studios for over two decades.

Gene Kiniski was a larger-than-life character whose personality and wider impact could never have been contained within the ring ropes of the squared circle.

“I remember Gene always carrying himself as a champion,” said another Canadian wrestling legend, Bret ‘The Hitman’ Hart in 2007. “He stood big and strong with his crew cut with those big ears and that snarly face, a face only a mother could love. He was one of the greatest NWA champions I ever watched and he was probably one of the fittest men to ever lace up a pair of wrestling boots. He was never fancy, but he didn’t need to be, he was as rugged and tough as every champion before him.”

“I remember Gene always carrying himself as a champion,” said another Canadian wrestling legend, Bret ‘The Hitman’ Hart in 2007. “He stood big and strong with his crew cut with those big ears and that snarly face, a face only a mother could love. He was one of the greatest NWA champions I ever watched and he was probably one of the fittest men to ever lace up a pair of wrestling boots. He was never fancy, but he didn’t need to be, he was as rugged and tough as every champion before him.”

“Gene’s success and confidence was an inspiration for me personally,” said Chris Wilson, one of Canada’s top amateur wrestlers in the 1990s and a 1998 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “For a ‘nobody’ from Edmonton to rise to the levels he did and for so long was amazing and showed kids like me what could be possible. I admired him as much as I did Bobby Orr and Guy Lafleur.”

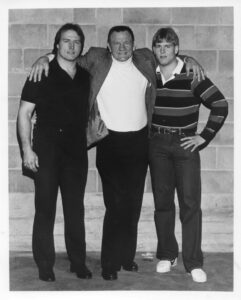

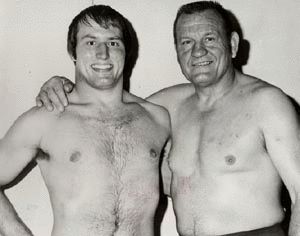

“He was bigger than life,” said Gene’s son Kelly Kiniski, a former professional wrestler as well, in a recent interview. “He’d cause riots all over the place during his matches—Toronto, Vancouver, everywhere. Then the next time the place would be packed because people wanted to see if another riot would happen.”

“Whatever you think of him, Gene was not just a wrestler and I think that’s why he struck a chord with so many people,” said Steve Verrier, author of the 2019 book, Gene Kiniski: Canadian Wrestling Legend. “He was not this one-dimensional person you sometimes associate with wrestling. He was a hundred times what you saw on television. Of course, he amplified that part of his personality to make an impact on TV and to achieve success. But I was amazed at just what a wide-ranging fellow he was. He was a great wrestler, but that’s just a tiny fraction of who he was.”

Raised in tiny Chipman, Alberta during the hardscrabble years of the Great Depression, Gene was the youngest of six Kiniski children to parents Nicholas and Julia Kiniski. When Gene was approaching his teens the family moved to Edmonton. It was there while attending St. Joseph Catholic School that Gene began boxing, wrestling, and playing football. He was coached in the finer points of wrestling at the Edmonton YMCA by Leo Magrill, who was largely blind but still able to direct Gene.

“He really gave me my foundation,” Gene told The Province in 1971. “He was my guiding light.”

By high school Gene seemed to be the largest kid everywhere he went, already six feet tall and well over 200 lbs. A gifted, natural athlete, he won the 1947 Alberta provincial wrestling championship in the heavyweight class because he was the only athlete large enough to contest this weight class. In 1949 he again took the Alberta provincial wrestling championship, this time in the open class.

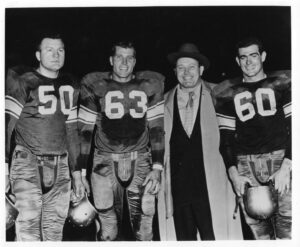

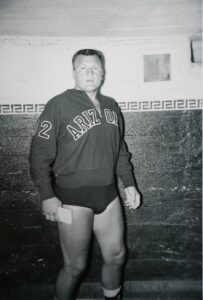

After playing junior football with the Edmonton Maple Leafs, Gene was spotted by Edmonton Eskimos coach Annis Stukus, a 1998 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee, and in 1949 he played on Edmonton’s defensive line. The following year Gene accepted an athletic scholarship at the University of Arizona and played two seasons for the Wildcats. While at Arizona he took a course on public speaking and he credited it with helping him learn to “express myself,” a skill that came in handy later in his wrestling career. He also continued to wrestle at the amateur levels in Arizona and won the state title twice. It’s believed Gene may be the only athlete to hold both a Canadian provincial and US state amateur heavyweight wrestling championship.

After playing junior football with the Edmonton Maple Leafs, Gene was spotted by Edmonton Eskimos coach Annis Stukus, a 1998 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee, and in 1949 he played on Edmonton’s defensive line. The following year Gene accepted an athletic scholarship at the University of Arizona and played two seasons for the Wildcats. While at Arizona he took a course on public speaking and he credited it with helping him learn to “express myself,” a skill that came in handy later in his wrestling career. He also continued to wrestle at the amateur levels in Arizona and won the state title twice. It’s believed Gene may be the only athlete to hold both a Canadian provincial and US state amateur heavyweight wrestling championship.

“He was a very good amateur athlete,” emphasized Verrier and perhaps no other example illustrates this better than the fact that his strong play on the football field for the University of Arizona generated serious interest among NFL teams who wanted to sign him. The Los Angeles Rams, the reigning NFL champions in 1951, were ready to sign Gene to a contract but were unable to get the NFL to waive its eligibility rule for college athletes who hadn’t played a full four years. Being ineligible for the NFL, Gene headed north back to Edmonton to suit up once again for the Eskimos, but seriously injured his right knee in his first game. He spent the next year rehabbing his knee and returned to play 13 games for Edmonton in the 1953 season.

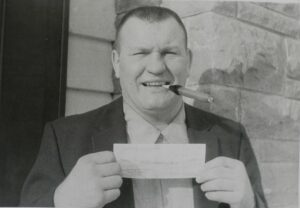

By that point Gene had already quietly begun wrestling professionally while still at the University of Arizona. What began as a part-time gig as a bouncer working the door for local wrestling shows turned into actually stepping into the ring and wrestling in the matches himself not long after. He made his professional debut at the Tucson Sports Center on February 13, 1952 defeating Curly Hughes in the main event in what the local press called “a roaring success.”

When Edmonton refused to give Gene a pay raise after the 1953 season, he quit football and threw all his chips in on pro wrestling. It may have been the best decision he ever made. For a talented athlete who knew how to work a crowd, his rise was rapid. By 1954, Gene was headlining main event matches in Tucson and later while wrestling in Los Angeles, he won his first major title belt, the NWA International Television Tag Team championship with partner John Tolos. Soon he was even being booked in NWA Heavyweight title matches against champion Lou Thesz.

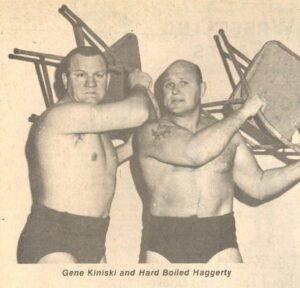

From there Gene began travelling all over North America wrestling most of the top wrestlers of the era. It really is a who’s who of legends, pioneers, and champions and within just a few years from his start Gene was already considered among the best of them. Those he faced included Thesz, Buddy Rogers, Sandor Kovacs (who later became his business partner in All-Star Wrestling), Whipper Billy Watson, Fritz von Erich, Killer Kowalski, Gorgeous George, Don Leo Jonathan, Bobo Brazil, Vern Gagne, Bruno Sammartino, Sweet Daddy Siki, Haystack Calhoun, Wahoo McDaniel, Abdullah the Butcher, and Pedro Morales, among many others.

By the time Gene made his first appearance in Vancouver in 1957 wrestling Whipper Billy Watson during an extended feud, he was one of the biggest attractions in pro wrestling. He had almost perfected his heel character that could rile up wild wrestling crowds like few others. One of the most chaotic appearances occurred in Montreal in the summer of 1957 when he antagonized the fans to the point that a near-riot broke out as dozens of folding chairs were thrown into the ring, “enough…to start a furniture store” one report said. It wasn’t the last riot Kiniski would be responsible for.

By the time Gene made his first appearance in Vancouver in 1957 wrestling Whipper Billy Watson during an extended feud, he was one of the biggest attractions in pro wrestling. He had almost perfected his heel character that could rile up wild wrestling crowds like few others. One of the most chaotic appearances occurred in Montreal in the summer of 1957 when he antagonized the fans to the point that a near-riot broke out as dozens of folding chairs were thrown into the ring, “enough…to start a furniture store” one report said. It wasn’t the last riot Kiniski would be responsible for.

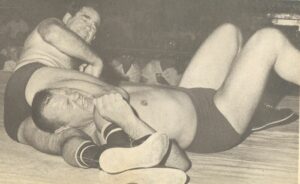

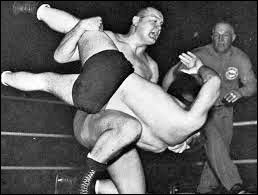

Gene also became known for his athleticism in the ring, his ability to carry less-talented opponents to an entertaining match, and of course, his toughness.

“In the ring he was very, very tough,” said son Kelly. “When I started training with my dad, just home from West Texas State in great shape from all the sports I played, and he would just wear me out. Just hitting those ring ropes, my whole side would just swell up and be black, blue, and green. I just couldn’t believe it.”

In 1961, Gene won his first major singles title, the American Wrestling Association (AWA) heavyweight title defeating Vern Gagne and held the title for a month in the Minneapolis-based promotion. After returning to wrestle in BC many times since his 1957 debut in the province that he would most come to be associated with, later in 1961 Gene joined the NWA’s Vancouver territory and largely remained connected to BC for the remainder of his life from this point on. Over the next two years, Gene helped drive a wrestling boom in the Pacific Northwest as the territory’s top heel. In July 1962, he wrestled NWA world heavyweight champion Buddy Rogers before a massive crowd estimated at 16,000 spectators in Vancouver. He then took his antics to Japan for the first time in 1964 and over the next decade became one of the most popular wrestling attractions in Japan as well.

That same year Gene also made his debut in the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF), precursor to the WWF/WWE. He wrestled WWWF champion Bruno Sammartino several times in main events at New York’s Madison Square Garden. The legendary Sammartino, in the midst of the longest WWWF/WWF/WWE title reign in history (ultimately nearly eight years from 1963-71) held Gene in high regard.

“I always had the utmost respect for Gene Kiniski,” Sammartino told Steve Verrier in 2017. “I thought he was a tremendous performer. I respected him and appreciated him for always being in shape—that he could go the distance, so to speak. If he had to go a half hour [or] one hour, it didn’t matter. I think he was one of the very top guys in his time.”

Gene also partnered in tag teams with legends Gorilla Monsoon and Classy Fred Blassie and it was with Waldo von Erich that he won the WWWF US Tag Team Championship in 1965, the only WWWF title he would ultimately win in his career. After a dispute over pay with WWWF owner Vince McMahon Sr., Gene bolted and it led to the highlight of his career.

Gene also partnered in tag teams with legends Gorilla Monsoon and Classy Fred Blassie and it was with Waldo von Erich that he won the WWWF US Tag Team Championship in 1965, the only WWWF title he would ultimately win in his career. After a dispute over pay with WWWF owner Vince McMahon Sr., Gene bolted and it led to the highlight of his career.

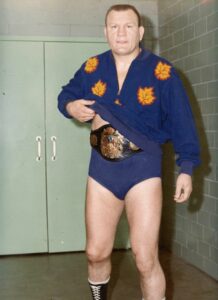

At that time St. Louis was considered the top wrestling territory in North America and the NWA World Heavyweight championship was representative of the top pro wrestler in the world. Lou Thesz was the reigning champion and is still considered likely the greatest NWA title holder in history, but others who later held the belt include legends such as Terry Funk, Harley Race, and Ric Flair. On January 7, 1966, Gene took on Thesz before over 11,000 spectators at the Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis and pinned the great champion in a best-two-out-of-three-falls victory after softening him up with three backbreakers, his finishing move.

“Winning the world title, that had to be the ultimate for him,” said Kelly.

“He’d had success up to that point, but then he clearly became the best wrestler in the world. Winning that title, that was the peak of his career I think,” agreed Verrier.

Gene was 37 years old and at the pinnacle of the wrestling world. He would hold the NWA World Heavyweight Championship for the next three years. As the new champion, suddenly every territory wanted to book him and Gene would spend much of the next few years on airplanes and in hotels when not in the wrestling ring, crisscrossing the continent and wrestling hundreds of times a year.

“I thought my dad just lived at the airport,” laughed Kelly. “I told the teacher that. The teacher called my mom and they had a big powwow about that. My mom said, ‘That’s sort of correct. He’s always on jets and flying all over the world.’”

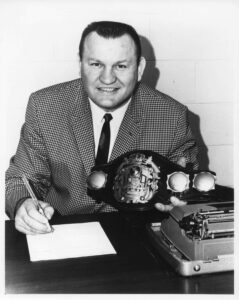

Almost every day there was another booking to get to in another city. In 1967 alone, Gene wrestled in over 150 NWA title defenses in the US and Canada, plus other non-title and tag team matches. On top of that were all the media appearances for pre-match promotion. It was a dizzying pace and incredible pressure to keep up with all obligations.

Almost every day there was another booking to get to in another city. In 1967 alone, Gene wrestled in over 150 NWA title defenses in the US and Canada, plus other non-title and tag team matches. On top of that were all the media appearances for pre-match promotion. It was a dizzying pace and incredible pressure to keep up with all obligations.

“As champion, you just can’t imagine the stress in trying to get to the matches, through snowstorms, planes being late,” explained Kelly. “When Jack Brisco, another champion, handed the title off, he threw his watch away and said, ‘I’ll never look at another clock again.’ Somehow all those world champions, it takes a toll on them one way or another.”

The mental and physical toll on Gene, particularly in those three years as NWA champion, was incredible.

“The number of times he was hurt and so sick he couldn’t hardly get off the couch,” recalled Kelly. “I’d see him throw up and have terrible nerves. But he’d jump in the car and no matter what off he’d go, he’d wrestle. He used to say, ‘If I die, throw me in the ring and I’ll be able to go another three rounds.’”

Injuries were common but Gene had the sheer tenacity to just wrestle through them.

“A few years after he was world champion, he went to the doctor in Vancouver and the doctor asked him when he’d broken his ankle,” said Kelly. “‘I didn’t ever break my ankle,’ my dad said. The doctor said he actually had, it was a clean break. My dad said, ‘Well I remember I just had to wrap it up every night. It would hurt me on the way to the ring but once I was wrestling I never felt it.’ “The doctor just shook his head.”

One of the highlights of Gene’s title reign was an epic 65-minute match in Tokyo against Shohei ‘Giant’ Baba which many wrestling observers still consider one of the greatest matches in Japanese wrestling history.

“[Kiniski] was as good a champion as there ever was,” the legendary Terry Funk told Verrier. “He was loud, he was tough, he was scary, but he had a heart of gold [and] a tremendous amount of class.”

It was also during his NWA title reign that Gene and his family—wife Marion and sons Nick and Kelly—made their permanent home in Blaine, Washington. He had fallen in love with BC and was a quiet owner in the Vancouver-based Northwest Wrestling Promotions/All-Star Wrestling with Sandor Kovacs and Don Owen, but chose Blaine just over the border so he could keep his green card and wrestle anywhere in the US, while still being close to Canada.

It was also during his NWA title reign that Gene and his family—wife Marion and sons Nick and Kelly—made their permanent home in Blaine, Washington. He had fallen in love with BC and was a quiet owner in the Vancouver-based Northwest Wrestling Promotions/All-Star Wrestling with Sandor Kovacs and Don Owen, but chose Blaine just over the border so he could keep his green card and wrestle anywhere in the US, while still being close to Canada.

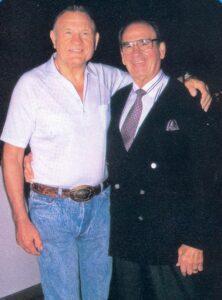

“It’s clear that he considered himself a British Columbian, even when he was living over the border [in Blaine, Washington],” said Verrier. “To him, Blaine was a suburb of Vancouver. Vancouver was his community. He was so active in BC and so respected here, and held in some esteem by other members of the sporting community in BC.”

Maybe one of the best examples of this comes via another BC Sports Hall of Famer, ‘Dr. Sport’ Greg Douglas, inducted in 2010, who shared with Verrier this gem of a story involving one of the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s Honoured Teams, the 1968-69 Vancouver Canucks:

“[Portland] were heavily favoured to sweep Vancouver [in the Western Hockey League final]. I talked to Gene and … asked him if he would come down to our dressing room… He was more than willing and went into that room and captivated it, just as I was hoping he would… He was telling them how important it [was] to believe in themselves… The players just sat there in stone silence, looking at him, and they all knew who he was. These guys were from all over North America. The story is that we swept Portland in four games and won the championship.”

Besides being a silent owner in the All-Star Wrestling promotion, in between other appearances all over North America Gene squeezed in as many as possible on the popular All-Star Wrestling CHAN-TV/BCTV program that was broadcast weekly across Canada. It only raised Gene’s profile higher to the point where he was a truly national figure in Canada over the next several years.

But after carrying the NWA title belt for over three years, Gene had had enough. He relinquished the title to Dory Funk Jr. on February 11, 1969 in Tampa. But that didn’t mean he suddenly disappeared from the public eye. For years, perhaps decades, Gene remained one of the most recognizable and memorable figures on the BC sport scene. In fact, in the late 1960s and through the 1970s, it’s quite likely Gene Kiniski was the most well-known British Columbian sports figure in other parts of the world outside of BC. Some argue at that time he was the most famous BC figure in any field, period.

The best example to illustrate this occurred in 1972 when Muhammad Ali was in Vancouver for his second fight with the great Canadian journeyman boxer George Chuvalo. Ali went on Jack Webster’s CKNW radio program and they paired him off with none other than Gene Kiniski in what was billed as ‘The Battle of the Windbags.’ Gene went toe-to-toe—or perhaps lip-to-lip is more appropriate—with Ali and more than held his own in what has to be one of the greatest sports radio segments in BC history. A recording of their highly-entertaining encounter can be found on Youtube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqYxCHxMoJU&t=745s

After dropping the NWA title, Gene would continue to wrestle mostly out of Vancouver, but also around North America and overseas as a top attraction for well over the next decade and well into his fifties. Many of the wrestlers he faced from this period would become superstars in the WWF/WWE era including ‘Superfly’ Jimmy Snuka, Bob Backlund, Jake ‘The Snake’ Roberts, The Iron Sheik, ‘Rowdy’ Roddy Piper, Sgt. Slaughter, The Bushwhackers, and Andre the Giant, who Gene fought to a double count-out in Vancouver in July 1974. One of his final in-ring highlights was wrestling the legendary Ric Flair for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in St. Louis at the age of 53 in 1982. Flair said of Gene after, “Boy, he’s a tough son of a gun.”

After dropping the NWA title, Gene would continue to wrestle mostly out of Vancouver, but also around North America and overseas as a top attraction for well over the next decade and well into his fifties. Many of the wrestlers he faced from this period would become superstars in the WWF/WWE era including ‘Superfly’ Jimmy Snuka, Bob Backlund, Jake ‘The Snake’ Roberts, The Iron Sheik, ‘Rowdy’ Roddy Piper, Sgt. Slaughter, The Bushwhackers, and Andre the Giant, who Gene fought to a double count-out in Vancouver in July 1974. One of his final in-ring highlights was wrestling the legendary Ric Flair for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in St. Louis at the age of 53 in 1982. Flair said of Gene after, “Boy, he’s a tough son of a gun.”

Having been an amateur wrestler himself at one time, Gene was steadfast in his support of the sport in the Vancouver area, particularly when his son Nick was one of the top amateur wrestlers in Canada wrestling out of Simon Fraser University in Burnaby.

“Gene attended almost all of our SFU wrestling events during the four or five years his son was involved and any big event we hosted after this time,” said SFU wrestling coach Mike Jones, who was himself inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 2011. “He was never shy about giving technical and tactical advice to any of our athletes he thought he might help. I did not know Gene as an amateur and truthfully never saw him compete as a professional, but he brought a certain intensity to everything he did and I am sure I would not like to line up across from him.”

Nick was an alternate on Canada’s 1984 Olympic wrestling team and one of his SFU teammates who Gene got to know well was Bob Molle, a 1999 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. Molle looked to be a medal contender going into the Los Angeles Olympics until disaster struck shortly before the Games. In a letter of support for Gene’s BC Sports Hall of Fame nomination, Bob told the story of how Gene forced him to make a miraculous recovery:

“Out of nowhere I learned I had a sequestered disk, needed an operation right away, and had no chance of competing in the Olympics. Or so I thought. The day after I got out of back surgery, unable to even walk, Gene Kiniski showed up at the hospital, saying, in effect, ‘Come on, Bob. No time to waste. You’ve got to get training.’

“But in my mind my Olympic dream was over. That’s what the doctors said, and I didn’t think there was a chance in the world I could compete—especially not with the Olympics just about to get underway. I couldn’t walk, I was in pain, I’d lost a lot of weight, and there was no way I’d be able to train myself back into competitive shape in two short weeks.

“But in my mind my Olympic dream was over. That’s what the doctors said, and I didn’t think there was a chance in the world I could compete—especially not with the Olympics just about to get underway. I couldn’t walk, I was in pain, I’d lost a lot of weight, and there was no way I’d be able to train myself back into competitive shape in two short weeks.

“But then Gene convinced me otherwise. He started me out with simple exercises—as simple as walking or stretching—and convinced me that I’d be in Los Angeles two weeks later to compete in the Olympics. Every day that I was in the hospital, Gene was by my side pushing me just a little harder, insisting that I’d worked too hard to give up now.

“Confounding the doctors who had told me I had no chance of recovering so quickly after the surgery, I got clearance to compete in the Games, and over the course of the competition I managed to earn a silver medal. That would not have happened without the motivational and inspirational influence of Gene Kiniski.”

From the early 1980s on, in semi-retirement Gene wrestled sporadically, but his popularity and celebrity never waned for the rest of his life. When he appeared on Peter Gzowski’s 90 Minutes Live show on the CBC in 1978, Gene in full wrestling character fired a memorable line at Gzowski for theatrical effect, but it also contained a kernel of truth to it.

“If Prime Minister Trudeau and I walked down the street, they’d say, ‘The guy with the crewcut is Kiniski. I don’t know who the other guy is.’”

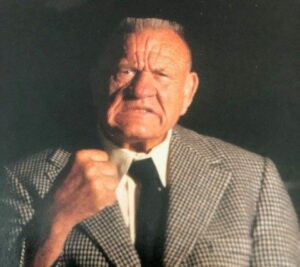

“Even when he was in his eighties,” Kelly noted, “wrestling fans would come up to him all the time. He’d say, ‘Where are you from? Oh, Prince George! Oh yeah, I used to stay at such-and-such hotel…’ And he’d just start talking to them and it would be an honour and a privilege for him. People just knew him. Plus he’d gone to all these small towns while wrestling. All over the Island and through British Columbia, all over Canada and the United States.”

When Gene was announced as one of the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s 2021 inductees in October 2021, his other son Nick shared one of Gene’s favourite lines: “There are steam ships, sailing ships, and battleships, but there is no ship like friendship.”

Gene had friends all over the world from world champion wrestlers and top athletes to well-known politicians and sports media figures to average locals in Blaine and Vancouver.

Gene had friends all over the world from world champion wrestlers and top athletes to well-known politicians and sports media figures to average locals in Blaine and Vancouver.

“He made friends far beyond the wrestling world,” remembered Kelly. “When he was in an old folks home late in his life, there’d be lines of people coming in saying goodbye to my dad—ten, twelve people in line. Finally they just said he can’t see that many people constantly. It was just shocking the amount of people whose lives were touched by my dad.”

Verrier, who spent 18 months writing his excellent book on Gene, summed up the great wrestler’s career nicely.

“As great an impact he had on the Pacific Northwest, he had a similar effect on a lot of other places. He was huge in St. Louis, which was the center of professional wrestling in United States for many years. Wherever he went, he was ‘the guy’ pretty much. Kiniski was in the main event everywhere. Kiniski’s impact certainly extended beyond wrestling especially in Canada. Wherever he went he seemed to draw enormous attention. He’s one of those wrestlers and personalities from his era that people just can’t forget about. There may be doubts that a professional wrestler should be inducted, but if you look at the full picture of his story, I don’t think there is any doubt that he should be honoured.”

Kelly is equally happy about Gene’s induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

“I’m just excited about it and I think all wrestling fans in Canada will be excited about it too. I don’t think anyone promoted Canada more than my dad all around Japan the United States, you know, being ‘Canada’s Greatest Athlete.’ He would just be so excited about it.”

Gene was honoured in various wrestling halls of fame during his lifetime including the George Tragos-Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2004), the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2007), the NWA Hall of Fame (2009), and the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2008). When Gene was inducted into the latter he shared a touching acceptance speech that if he were alive today he might have shared something similar at his BC Sports Hall induction in June:

“The oldest profession in the world is the art of deceiving yourself. I am not going to deceive myself this evening… The reason that I’m here standing in front of you is because of my peers, and because of the people who made it all possible, wrestling fans. Without you, we wouldn’t be here. Thanks for making my life so special, so enjoyable.”

As part of the Class of 2021, Gene Kiniski will be formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Pioneer category at the annual Induction Gala to be held June 9, 2022 at the Vancouver Convention Centre.

*Note: A special thank-you should be made to author Steve Verrier for several quotes and a good deal of background information that was sourced from his excellent book Gene Kiniski: Canadian Wrestling Legend, published in 2019 by McFarland. Copies can be purchased online here: https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/gene-kiniski/