1961-62 Vancouver Firefighters: The Tightest of Teams – 2021 Inductee Spotlight

May 7, 2022By Jason Beck

It’s one of the cardinal rules of team sports.

The teams that are tightest off the field will often be the most successful on the field. You care about your teammate playing beside you so much you’d give that little bit extra to help them out, run through the proverbial wall for them if needed. If you’ve played on championship winning teams, you’ll know there is a lot of truth to this.

And then there is the 1961-62 Vancouver Firefighters, a men’s soccer team who took this to a whole other level.

It’s common for successful teams to bond away from the field, maybe do a team-building activity together or gather socially sometimes even with their families. The Firefighters certainly did that. But show me another BC team in any sport that also lived and worked together on top of everything else. All but two members of the ’61-’62 Firefighters players and management team worked for the Vancouver Fire Department. Maybe the great Trail Smoke Eaters hockey teams of the 1930s and 1960s are the one comparable, as most of the Smokies players worked by day at the Cominco smelter. But you can argue that they didn’t face the pressure-packed working environment that the Firefighters often found themselves in.

Every day the Firefighters showed up for a shift at the fire hall there was a good chance they’d be working together in incredibly dangerous conditions putting their lives on the line fighting a roaring blaze often to save the lives of others and sometimes their own. You can’t help but grow tighter as a group in that kind of situation.

Every day the Firefighters showed up for a shift at the fire hall there was a good chance they’d be working together in incredibly dangerous conditions putting their lives on the line fighting a roaring blaze often to save the lives of others and sometimes their own. You can’t help but grow tighter as a group in that kind of situation.

“As a firefighter when you go to work, you’re a team going to a situation and at a fire, you better work well together,” said Gary Stevens, a young outside back on the 1961-62 Firefighters. “There was no ego in our team. Absolutely none. Everybody did everything together really. I think it definitely helped us.”

Knowing this about the team’s background, maybe it’s not so surprising that the Firefighters would become a dynasty in BC men’s soccer and the 1961-62 team considered one of the greatest in BC and Canadian soccer history.

The Firefighters have a long history of men’s soccer clubs in Vancouver going back as far as the 1940s and continuing into the late 1990s. The 1960s were a golden era for the Firemen as they won five Province Cup provincial championships in seven years (1961-63, 1965, 1967), one Canadian championship (1965) along with one other Canadian final appearance (1961), and four Pacific Coast Soccer League (PCSL) titles in five years (1962, 1964-66).

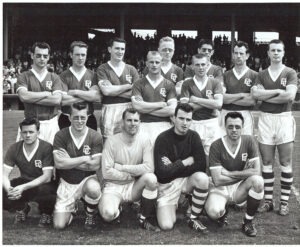

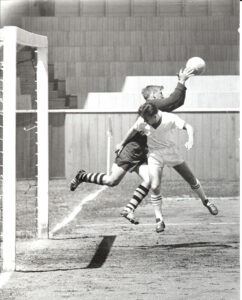

The 1961-62 squad may have been the best of the era with a nice mix of older experienced veterans and young rising stars. They were anchored by their great goalkeeper Ken Pears, a 1986 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee, considered by many to be one of the greatest goalkeepers ever produced in Canada. Center half Bob Mills was their captain. Left half Doug Greig was another veteran leader.

“I thought he was the best player in the Pacific Coast League for quite a few years,” said teammate Stevens. “He was like a playing coach out there. He had such vision, if there was nothing in front, he’d move it back and we’d start all over again like they do now. Well, that was unheard of then.”

Much of the scoring was handled by forward Jim Blundell and Eddie Bak, a former forward who’d been converted to a speedy outside back. The Firefighters had speed to burn on their wings as Stevens, the youngest player on the team at just 19 years of age and possibly the fastest, raced up and down the other flank at outside back. Using speed at the back was new at a time when most fullbacks then tended to be slower, hard-tackling tough guys. It gave the Firefighters another attacking dimension that most teams had no answer for.

When injuries piled up in mid-season, veteran center forward Art Hughes came out of temporary retirement and rejoined the team. And then there were other stalwarts like Dave Hutton, Art Bennett, Bob MacKay, Terry McKibbin, Gordie Ion, Louis Trischuk, Ernie Durante, Al Lenfesty, Gord Nordby, and Bud Walton. Dave Sullivan served as coach, Deryl Hughes was the manager, and Jim McGuckin was the trainer.

“It was a good mix of really experienced guys,” summed up Stevens, ultimately one of seven members of this team to be inducted into the Canada Soccer Hall of Fame along with Bak, Blundell, Greig, Hughes, Ion, and Pears.

“It was a good mix of really experienced guys,” summed up Stevens, ultimately one of seven members of this team to be inducted into the Canada Soccer Hall of Fame along with Bak, Blundell, Greig, Hughes, Ion, and Pears.

All but two of the players and management worked at the Vancouver Fire Department. The only exceptions were Bennett, who was a drywaller, and the diminutive Trischuk, who didn’t meet the department’s minimum height requirement, otherwise he likely would have too. At that time, all Vancouver firefighters needed to be between 5’9” and 6’1” in height for safe operating and carrying of equipment, such as 50-foot wooden ladders, which took several guys of similar height to move and set up.

You’d think having so many team members working in the same profession, especially one that often involves responding to unexpected emergencies, would wreak havoc on consistently fielding a strong team, but rarely was it an issue for the Firefighters owing to good planning.

“It might be a problem if you had a big fire in the morning [the day of a game], but you usually had someone coming in for you at lunch time,” explained Stevens. “If you were at a fire, he’d come to the firehall, get his gear—the hall was never locked—and drive down to the fire and join the effort. You’d come out, get in his car, and drive back to the hall, change, get your soccer gear, and go off to the game. The fire department was good because they allowed guys to trade shifts. They didn’t let you take shifts off, but they allowed you to get a sub for shifts. So you have to credit the fire department for that. It was really well organized.”

Stevens. “If you were at a fire, he’d come to the firehall, get his gear—the hall was never locked—and drive down to the fire and join the effort. You’d come out, get in his car, and drive back to the hall, change, get your soccer gear, and go off to the game. The fire department was good because they allowed guys to trade shifts. They didn’t let you take shifts off, but they allowed you to get a sub for shifts. So you have to credit the fire department for that. It was really well organized.”

They practiced at Clinton Park and their original home field was the Powell Street Grounds (today known as Oppenheimer Park) in east Vancouver (when Firefighters joined the PCSL matches were at Callister Park). The field only had one tiny dressing room, but the Firefighters found a unique solution that only brought their work and personal lives closer together. Instead of changing at the field for home games, they just changed together at the fire hall.

“We parked at the fire hall down the street, the old Hall No. 2, went upstairs, changed, left all our gear there, walked up the street, and played the game,” recalled Stevens. “Afterwards, we’d walk back down to the hall, then showered and changed, and usually walked kitty-corner to the Patricia Hotel and drank beer afterwards.”

“We were so intense,” said Pears to The Province in 1990. “That’s probably why we were so successful. We played together, drank together. That’s what sports is all about.”

“We were so intense,” said Pears to The Province in 1990. “That’s probably why we were so successful. We played together, drank together. That’s what sports is all about.”

Later, when someone at the department took issue with the team using the firehall, they used the Patricia Hotel as their locker room, which had showers and chairs in the basement.

“We would walk up the alley, down into the basement, change, shower, and then just walk upstairs and have a drink,” chuckled Stevens. “That was our locker room.”

That tightly knit togetherness and team spirit was obvious even to opponents.

“Because of that common background the team had a shared level of on-the-field determination and commitment which, along with their soccer skills, contributed greatly to their success,” noted Dave Stothard, a Canada Soccer Hall of Fame inductee who battled Firefighters on the pitch countless times as a member of Westminster Royals and Victoria United.

“Everybody wanted to play for the Firemen,” emphasized Stevens. “We [were] always the team that stayed in the dressing room four or five hours after the game.”

After making it all the way to the 1961 Canadian national championship final before narrowly falling 1-0 to Montreal Concordia, a professional side reportedly assembled for $200,000, the 1961-62 season was the Firefighters’ first back up in the PCSL since 1955-56 after several seasons playing in the Vancouver & District Mainland League. Many considered the PCSL the top league in Canada at that time.

Most league matches were held at Callister Park near the PNE and regularly drew several thousand spectators to the cozy wooden structure. At one time Callister’s grass field was an immaculate emerald carpet, but later largely destroyed by the PNE’s insistence on using the pitch as an overflow parking lot for vehicles, as well as holding rodeos and later demolition derbies, which reduced the pitch to nothing but dirt. Players grew accustomed to surveying their typical area of the field for animal droppings or worse, automotive debris—both serious dangers to any player willing to risk a slide tackle. In fact, Terry McKibbin’s career nearly ended due to an infection caused by a piece of shrapnel he slid into that scraped his leg.

Although some players were now sporting lighter Adidas cleats, many were still wearing heavy leather boots with leather disks or strips nailed into the sole for traction. The balls were also usually leather, which could be a problem for much of the year here on the Wet Coast. Dubbin was applied before matches so the ball wouldn’t soak up as much water. It helped, but not much.

Although some players were now sporting lighter Adidas cleats, many were still wearing heavy leather boots with leather disks or strips nailed into the sole for traction. The balls were also usually leather, which could be a problem for much of the year here on the Wet Coast. Dubbin was applied before matches so the ball wouldn’t soak up as much water. It helped, but not much.

“Man, when those leather balls got wet they got so heavy,” marveled Stevens. “When one of them hit you in the head they left marks on your face. I don’t know how more people didn’t have concussions. They probably did. When they got wet they were impossible to kick, almost like a medicine ball.”

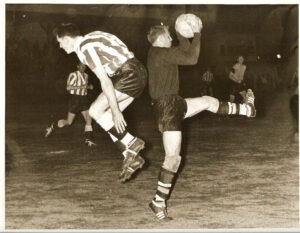

All season, the top three teams in the PCSL—Firefighters, Vancouver Columbus, and Victoria United—battled it out. In the Anderson Cup final in February 1962, Firefighters defeated Victoria 5-2 on a hat trick from Blundell and a brace from Bak. But the most memorable moment occurred in the first half when Victoria goalkeeper Barry Sadler collided with Firefighters winger Trischuk while converging on a dangerous through ball. Sadler and Trischuk began swinging at one another and their teammates rushed in resulting in a pile-up in the goalmouth. Then the fans got involved, about twenty rushing onto the field. Somehow the referee and team officials calmed things down and play was able to resume, despite smaller skirmishes in the stands, which only halted when the police arrived in the second half.

Yet it was the bitter rivalry between Firefighters and Columbus that ran particularly deep and often matches at Callister between the two sworn enemies could get similarly out of control. Scraps on the field were common and fistfights in the stands between rival fans even more so. Opposing sides did their best to antagonize the other often using creative means.

“One game Columbus was beating Firemen, and the Columbus fans put a yellow coffin on the field and the Firemen guys were going squirrelly trying to get at them,” chuckled Bob Lenarduzzi, a 1992 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee. “At the time I was seven years old…what a rivalry it was! Watching from the crowd with my dad and at the side of the pitch as a ball boy, these players became my role models and inspired me to pursue a pro soccer career.”

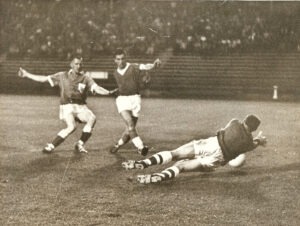

The rivalry drove a resurgence of interest in local soccer that year, breaking the league record for attendance and highlighted by a showdown in the final game of the PCSL season. Columbus had finished top of the table in the first half of the season, while Firefighters, with an overall record of 16 wins, five ties, and only four losses, battled back to win the second half. A one-game final to decide not only the PCSL championship, but also earn a trip to Los Angeles representing Canada in the Pacific International Soccer Championship, took place at Callister Park on May 20, 1962 before over 4200 fans—the largest crowd for a local soccer match in over a decade.

As they had all year, winning four of their five meetings head-to-head, Firefighters had Columbus’ number this season and cruised to a 5-1 victory. Goals were scored by Bennett (2), Blundell, Bak, and MacKay on a penalty shot. Pears, who finished with six shutouts on the season, was named the winner of the Austin Delaney Trophy as PCSL MVP. Hutton, Mills, Blundell, Stevens, and Trischuk were all named league all-stars. Surprisingly, their leading scorer Bak, who with 13 goals tied for fourth in the league, didn’t make the cut. But it didn’t really matter.

As they had all year, winning four of their five meetings head-to-head, Firefighters had Columbus’ number this season and cruised to a 5-1 victory. Goals were scored by Bennett (2), Blundell, Bak, and MacKay on a penalty shot. Pears, who finished with six shutouts on the season, was named the winner of the Austin Delaney Trophy as PCSL MVP. Hutton, Mills, Blundell, Stevens, and Trischuk were all named league all-stars. Surprisingly, their leading scorer Bak, who with 13 goals tied for fourth in the league, didn’t make the cut. But it didn’t really matter.

“We’re not a collection of stars, just a team,” emphasized captain Mills to the Vancouver Sun’s Jeff Cross after the match.

Four days later the Firefighters were boarding a plane heading south for Los Angeles in pursuit of the massive five-foot tall Kennedy Cup awarded to the winner of the Pacific International Soccer Championship featuring top teams from the USA, Canada, and Mexico. Besides the Firefighters, the other teams included the Los Angeles Kickers, San Francisco Scots, and Mexico Selects. Although they had never played any teams outside of Canada, going into the tournament the Firefighters were quietly confident.

“We just thought we’re going to be competitive against anybody on any given day,” recalled Stevens. “We just thought ‘What the hell?!’ right?”

But they would fly south without Blundell, one of their top scorers, who had just recently joined the Vancouver Fire Department and couldn’t get the time off to travel with the team. It could have been a major blow to the team’s chances, especially when they initially refused the PCSL’s recommendation to bolster their squad with top players from other teams in the league. But Firefighter management put their collective pride on the shelf and decided to pick up Normie McLeod from rival Columbus for the tournament. McLeod was coming off a career-high 19-goal season, good for second in league scoring. And although there might have been bad blood between the two clubs, McLeod fit right in with his new Firefighters teammates. It helped that he’d played youth soccer with Bennett and Hutton and knew a lot of the guys.

“There was a summer league then, a winter league,” explained Stevens. “Players were playing with all sorts of teams.”

After settling into their hotel and getting in a training session, the Firefighters faced Los Angeles Kickers in the one-game semifinal at LA’s Wrigley Field before over 8000 mostly Mexican fans, who had earlier watched the Mexico Selects defeat San Francisco 5-3 in the other semifinal. They were in for an epic match which might be one of the greatest ever played by a British Columbian team.

After settling into their hotel and getting in a training session, the Firefighters faced Los Angeles Kickers in the one-game semifinal at LA’s Wrigley Field before over 8000 mostly Mexican fans, who had earlier watched the Mexico Selects defeat San Francisco 5-3 in the other semifinal. They were in for an epic match which might be one of the greatest ever played by a British Columbian team.

The Firefighters started slow, perhaps still fighting heavy legs from their travel day, and fell behind 2-0 to LA early in the first half. But they quickly sprung to life and battled back to tie the score 2-2 by halftime on goals by Hughes and Bak. In the second half, McLeod’s presence paid immediate dividends as he put Firefighters ahead 3-2. The Kickers replied with a goal of their own with ten minutes remaining to knot the score at 3-3. Still tied after 90 minutes, the teams played 30 minutes of extra time and remained tied 3-3. After another 30 minutes of extra time they were still tied, but at 4-4. LA went ahead early, but Hughes tied it back up. Then another 15-minute session of extra time did nothing to settle things as the score remained 4-4.

Vancouver Sun sports columnist Dick Beddoes noted both sides were “staggering with fatigue… The game had disintegrated into a futile spasm of weariness.” The players on both sides were absolutely exhausted.

“I just remember us playing and playing and playing and then finally deciding to go to penalty shots,” said Stevens. “We couldn’t keep going because it was going to get dark. But nobody had ever gone to penalty kicks. We’d never seen that before.”

The referee and team officials huddled and came up with a unique penalty shootout format on the spot: each team would get three kicks and a player could take multiple shots for his team, all of them if you wanted. One team would take all their attempts first, then the other team would take theirs. The Firefighters won the coin toss and elected to shoot first. MacKay stepped up to the penalty spot.

“It was funny,” remembered Stevens. “His first shot went right down the middle and the goalie dove left. Then his next shot, right down the middle. But the goalie dove the other way! So the third one, Bob put it in the corner. He wasn’t the greatest penalty taker, but he had all the confidence in the world.”

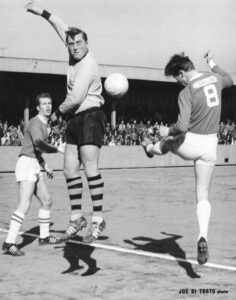

Next it was LA’s turn to shoot on Pears. But the man who’d be known as ‘Mr. Goalie’ in BC snared the first shot and that was the end of it. There was no need for LA to take their two remaining kicks. Firefighters had won 7-4.

It was over. Finally.

It was over. Finally.

Mexican fans stormed the pitch after Pears made his save and hoisted him onto their shoulders while chanting “Vive Zee Pears!” and carried him off the field.

The two teams had played almost two full games, 165 minutes officially, but likely approaching three hours with stoppage time, plus the shootout on top of that. It was the ultra-marathon of all soccer games.

“That Sunday game has to be the longest ever played,” said Bill Findler, president of the PCSL at the time.

And keep in mind, substitutions were limited then.

“Most guys played the whole time,” confirmed Stevens. “I was really tired, but I was young though, so remember that. I don’t how some of the older guys like Doug Grieg must have felt. You can’t imagine how we felt at the end of the overtime. We were thinking, ‘Shoot, are we ever going to recover from this?’ Because then we had to play Mexico.”

The Firefighters had three days to recover before the final. They spent the first day at a spa-like facility where everyone enjoyed time in the sauna, received massages, and relaxed.

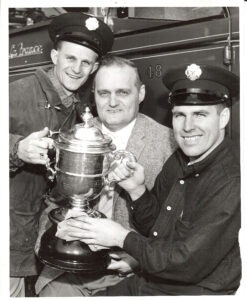

On May 30th, the Firemen were back at Wrigley Field to square off with the Mexico Selects, an all-star team of top Mexican players. On the line was the Kennedy Cup and $1250 in prize money. The Firefighters hoped to avenge Canada’s honour for the loss Mexico had inflicted on the Westminster Royals the previous year in the inaugural tournament. As they had for the semifinal, Firefighters were sporting red jerseys with white trim and an intertwined “BC” on their chests.

It would have been next to impossible to match that epic semifinal, but the final still had some moments of drama. Pears played brilliantly throughout stopping several dangerous chances. After a scoreless first half, early in the second McLeod raced through the Mexican defense and broke in on goal when the goalkeeper pulled him down in the 18-yard box. While McLeod was still on the ground, a Mexican defender took a kick at him. Hughes took off after the offender and chased him clear across the field before a group of Mexican supporters shielded him allowing things to calm down.

It would have been next to impossible to match that epic semifinal, but the final still had some moments of drama. Pears played brilliantly throughout stopping several dangerous chances. After a scoreless first half, early in the second McLeod raced through the Mexican defense and broke in on goal when the goalkeeper pulled him down in the 18-yard box. While McLeod was still on the ground, a Mexican defender took a kick at him. Hughes took off after the offender and chased him clear across the field before a group of Mexican supporters shielded him allowing things to calm down.

When order was restored, the referee awarded Firefighters a penalty shot. Mexican fans hurled hundreds of seat cushions onto the pitch in disapproval. Perhaps it unnerved McKay as after three straight perfect PK’s in the semi, his shot to the corner was stopped by the Mexican keeper. Later in the half Trischuk scored twice, both times set up by Hughes. Mexico scored late to make it 2-1 but that was as close as they came. Firefighters were the first Canadian team to capture the Kennedy Cup, donated by US president John F. Kennedy in 1961, the only sporting award to which the late American president ever lent his name.

Said Findler after: “What a tremendous finish to the best soccer season Vancouver has had in over twenty years. The Firemen played their hearts out here today and we’re all tremendously proud of them.”

After the final, a large banquet was held for all participating teams. When the Kennedy Cup was presented to the Firefighters, the Mexican team stood up and gave their opponents a special cheer.

“It gave us goosepimples,” said Stevens. “They were really good that way.”

Back at home, there was one more trophy to add to the Firefighters’ dream season. In the Province Cup provincial final they downed the Vancouver Canadians 3-1. Normally that would have earned the club the right to play at the national championship, but the BC Soccer Association refused to send any BC teams to the Canadian championship that year because of a dispute over costs associated with hosting other visiting provincial championship teams leading up to the national tournament. The Canadian Soccer Football Association wanted BC to pay for Alberta’s travel and accommodation costs.

“I remember Doug Grieg saying, ‘No, we’re not paying for them to come and try and beat us! Are you crazy?!’ So we didn’t go,” said Stevens.

“I remember Doug Grieg saying, ‘No, we’re not paying for them to come and try and beat us! Are you crazy?!’ So we didn’t go,” said Stevens.

It was unfortunate as the way they were playing Firefighters could very well have taken the national title that season as well, another major accolade in an already historic season. They wouldn’t have an opportunity the following season either as no national championship tournament was held at all in 1963. Regardless, in 1961-62 the Firefighters won every cup that was available to them and put together a season for the ages.

With many of the same core players, the Firefighters went on to win the club’s first Canadian national championship in 1965 and reclaimed the Kennedy Cup winning their second Pacific Coast International Championship in 1966.

Now sixty years later this spring almost to the day when they were victorious over Mexico in Los Angeles for their first Kennedy Cup, the Vancouver Firefighters will find themselves a place in the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Sadly, many of the team members are no longer with us, but their story will be remembered as long as the beautiful game is played in BC.

“We won just about everything we could that year,” said Stevens. “We deserve to be in here [the BC Sports Hall of Fame]. The guys were so stuck together, we would do anything for each other. This was more than just a team. There was something special about that group.”

As part of the Class of 2021, the 1961-62 Vancouver Firefighters will be formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Team category at the annual Induction Gala to be held June 9, 2022 at the Vancouver Convention Centre.