Kenny McLean: Canadian Rodeo Legend – National Indigenous History Month

June 30, 2021By Jason Beck

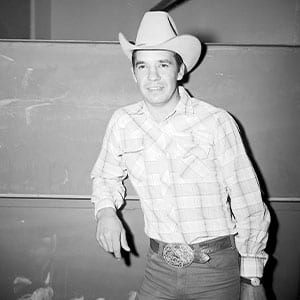

Kenny McLean may be the most underrated BC athlete you’ve likely never heard of. In the rodeo world, within the Syilx Nation, and in his home communities of Okanagan Falls and Vernon, BC he’s a legend, but outside of those circles his remarkable story is largely unsung.

Many have called Kenny the greatest Canadian rodeo cowboy of all-time for his impressive career accomplishments, his talent around horses, his versatility competing well in multiple events at the highest level, his longevity and consistency, his toughness, and his character in the way he gave back to the sport and others in it.

He was known for letting his riding do most of the talking. And the moments when he did speak, rarely was it about himself. Yet over the years tiny glimpses into who he was and what made him such an extraordinary rodeo athlete emerge and what better time than National Indigenous Heritage Month to pay tribute to a hero to many who followed the Canadian and American rodeo circuits in the 1960s and 1970s.

Born the youngest of ten children in 1939 in Penticton, Kenny grew up in Okanagan Falls on a ranch at the south end of Skaha Lake. His father was Scottish, a descendant of the Clan MacLean of Duarte Castle on the Isle of Mull off the west coast of Scotland. His mother was Indigenous, a member of the Syilx Okanagan Nation whose traditional territory stretches from the Rocky Mountains in the north all the way south into central Washington State. Like most topics, Kenny didn’t speak much of his Indigenous heritage, but one quote from a 1973 Vancouver Sun article was revealing of how he saw himself.

“I’m not an Indian or a white man,” he said. “I’m just myself.”

“I’m not an Indian or a white man,” he said. “I’m just myself.”

Growing up in O.K. Falls, Kenny hunted and fished in many of the same forests and lakes his Indigenous ancestors had known for thousands of years. When not attending Okanagan Falls Elementary and later Southern Okanagan High School in Oliver, there was much to keep young Ken busy on his father’s ranch where they raised horses and Herefords. By age two he was already riding horses.

“My brother and I built a chute and started riding,” he recalled in a 1962 TIME Magazine article.

By age 12, he was breaking colts for his father and by age 17, he entered his first rodeo, riding in a bareback event at an amateur rodeo in Keremeos.

“I rode my horse and there were a few guys who said I probably would have placed if I had spurred him out,” he recalled. “But I didn’t know anything about spurring horses out, or anything like that.”

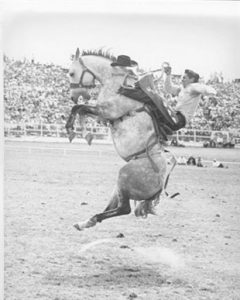

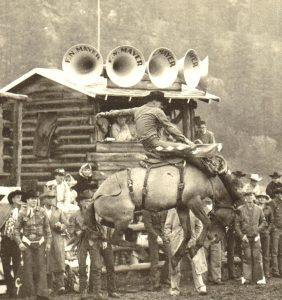

Saddle bronc riding had always been the showcase event at most rodeos, so Kenny shifted into that discipline and began practicing, riding up to seven times a day on the seven bucking horses on the ranch.

“The saddle I started with was a terrible old wreck,” he remembered. “It was an old Adams. We never had the stirrups tied up or nothin’. It had big old wide stirrups on it. None of us knew too much about anything really.”

But every day he was learning, developing a feel around horses and a determined toughness that would become legendary. In the spring of 1957 he won the bronc riding competition at the Kamloops rodeo, pocketing a cool $250. He still wasn’t convinced he had what it took to be a champion, so he continued practicing while helping out on ranches in the Okanagan Falls area and working odd jobs in the forest skidding logs, piling lumber, and felling trees. It doubled as good training.

There was one other issue that held him back. At first Kenny’s father wasn’t impressed with his son’s growing interest in the sport.

There was one other issue that held him back. At first Kenny’s father wasn’t impressed with his son’s growing interest in the sport.

“He didn’t think much of it [rodeo] to start with,” Ken recalled with a shrug.

But that would soon change. Kenny won the BC amateur bronc riding championship in 1958, then turned professional in 1959 and made an immediate impact at major rodeos throughout Alberta and BC winning his first Canadian saddle bronc championship. He would win that title four more times (1960, 1961, 1968, 1969) becoming the first Canadian cowboy to win the title three straight years and five years total.

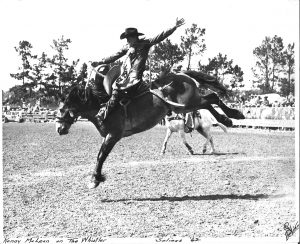

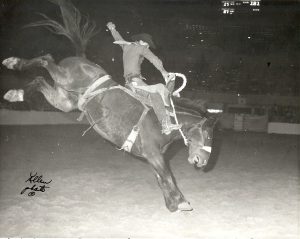

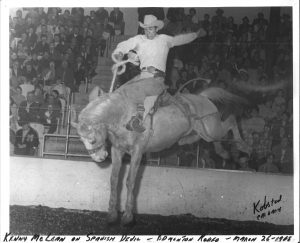

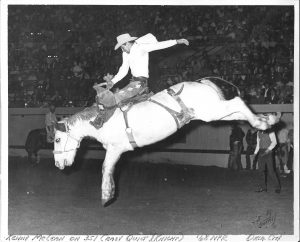

In 1961, Ken then turned his sights onto the tough Rodeo Cowboys Association (now called the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association or PRCA) circuit south of the border and turned heads with a seemingly effortless yet unorthodox right-handed riding style that scored points with judges and baffled his competitors.

“If you’re in time with the horse, your feet go forward when he kicks, and when he comes up, they go back,” he said describing what bronco riding was like to Ernest Hillen in a 1973 Weekend Magazine interview. “It’s like sitting in a rocking chair.”

Only a true cowboy could describe sitting atop a 1500-lb snorting, twisting, bucking beast that wants to do nothing but toss its rider as ‘sitting in a rocking chair.’ But then many have said the place where Ken felt most comfortable was in the saddle.

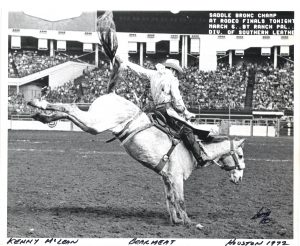

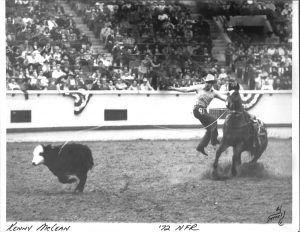

He qualified for the National Finals Rodeo for the first time that year—the first of his ten appearances at the NFR (1961-65, 1967-69, 1971 in saddle bronc; 1972 in calf roping). As of 2006 he was still the only Canadian to have qualified for the NFR in both of those disciplines. Over his career he never missed a payout at the National Finals, winning the bronc riding title a remarkable three times (1964, 1968, 1971)—the first cowboy ever to win three bronc titles—while also finishing 2nd once, 4th twice, and 6th three times. Even more amazing? In 77 career rides at the NFR, he was only bucked off his ride five times.

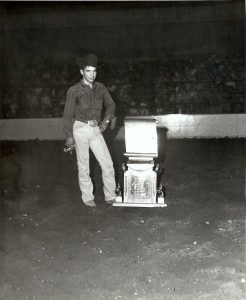

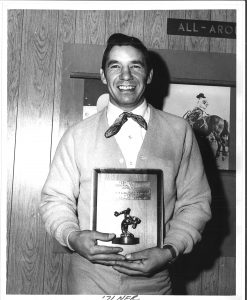

That first year he finished fourth overall in the bronc riding standings and was named the PRCA’s rookie of the year. The massive six-foot-tall trophy he was awarded resides today as the largest trophy in the BC Sports Hall of Fame collection.

That first year he finished fourth overall in the bronc riding standings and was named the PRCA’s rookie of the year. The massive six-foot-tall trophy he was awarded resides today as the largest trophy in the BC Sports Hall of Fame collection.

In 1962 he led from season’s beginning to end winning the RCA world bronc riding championship held in Los Angeles despite constant pressure from previous champions Winston Bruce and Marty Wood. Asked about the world championship, he fell back on an answer he used frequently when discussing his career accolades. “I was mighty lucky,” he said.

It was more than luck that made Kenny McLean so good in the rodeo corral. For one thing, at 5’10” and 170 lbs of hard muscle during his prime competition years, he was a true athlete wearing a Stetson and Levi’s blessed with amazing strength and agility and the willingness to work harder than just about anyone at his craft.

“He didn’t like being called a natural,” Ken’s son Guy McLean told the Vernon News in 2013. “He was one of the first rodeo guys to start working out and running. He rode six hours a day. He had natural abilities, yeah, but it was a lot of hard work.”

Ken often started each day with a series of push-ups and sit-ups for fitness and he approached every obstacle over the course of his day as a way to keep in shape. “I try to do things the hard way,” he explained. “I’ll jump over a gate instead of walking through it.”

Although he liked his cigarettes as so many cowboys did when he competed, he stayed away from alcohol.

“It don’t mix—riding and drinking,” he told Hillen. “Not if you’re going to rodeo, man! You’ve got to be an athlete. That’s what we are—athletes.”

If you were ever lucky enough to see him in the saddle or roping or steer wrestling, you didn’t dispute that for a second. And on the rare occasions when he was thrown from his horse, his pure athleticism was even more obvious.

If you were ever lucky enough to see him in the saddle or roping or steer wrestling, you didn’t dispute that for a second. And on the rare occasions when he was thrown from his horse, his pure athleticism was even more obvious.

“He’s a cat,” said Ken’s first wife Joyce in 1973. “When he’s thrown he always, always lands on his feet. He’s not thrown often, mind you. He’s more capable on a bucking horse than I am in high heels on flat ground. We were married three years before I saw him thrown for the first time—and sure, he landed on his feet. I swear he’s related to the cat family!”

That didn’t mean he breezed through his long rodeo career unscathed. Like any cowboy in the game long enough, he suffered his share of injuries. These included a broken foot, three broken noses, cracked ribs, torn rib muscles, sprained wrists, twisted knees, three broken teeth, dislocated thumbs, severe rope burns over most of his upper body including face and ears, and many cuts on his back from horses rearing up in the chutes and smashing him against the fencing. Despite this laundry list, he still felt fortunate.

“I’ve been lucky,” he said. “A lot get more broke up than that. I’ve seen one bull rider stepped on and killed.”

The courage of any rodeo cowboy was never in question and Ken was known as one of the bravest around.

“If I get feared of horses, I’d quit,” he said in 1973. “A horse falling backward in a chute and pinning you is pretty scary, I guess.”

Some ignorant observers claimed rodeo cowboys may have been brave, but they must also lack intelligence to willingly put themselves in such grave danger for the meagre rewards that Kenny’s era competed for. As the narrator put it in the 1972 National Film Board documentary Hard Rider, which profiled Kenny and his life on the RCA circuit, in bronc riding you might make $500 a ride or you might break your neck. But listen to Kenny discuss the intricacies of bronc riding and steer wrestling—one of the few topics he’d discuss at length—and the wisdom and broad knowledge of the man just pour out.

“Every performance is different, you never see two performances identical, I’ve yet to see,” he began. “Horses, a lot of times, you go to see one horse that you really look forward to seeing, that does something a little different or some guys get thrown off different, thrown off the back end. I think it pays a rodeo cowboy to go see every performance because you may have to get on this horse at the next rodeo and you can figure things out on how to ride him or how much head to give him. And same with steer wrasslin’. A calf may run off to the right. Once you really get to understand rodeo, you get to seeing all these little things. I mean to the ordinary person they probably don’t mean anything, but to a cowboy they mean a lot.”

“Every performance is different, you never see two performances identical, I’ve yet to see,” he began. “Horses, a lot of times, you go to see one horse that you really look forward to seeing, that does something a little different or some guys get thrown off different, thrown off the back end. I think it pays a rodeo cowboy to go see every performance because you may have to get on this horse at the next rodeo and you can figure things out on how to ride him or how much head to give him. And same with steer wrasslin’. A calf may run off to the right. Once you really get to understand rodeo, you get to seeing all these little things. I mean to the ordinary person they probably don’t mean anything, but to a cowboy they mean a lot.”

His intense determination and drive may have been his most defining characteristic as a competitor. His second wife Paula Jo once remarked: “You don’t want to play Scrabble with him. He’s got the whole dictionary memorized.”

Tiring of the exhausting travel from one rodeo to another for much of the year, after winning the 1962 world championship, Kenny returned home to Okanagan Falls to run his father’s ranch, while competing at just enough rodeos to make a living. He loved the thrill and skill of rodeo, which comes through in many quotes: “Ridin’ a real good bronc, you know, that throwed a lot of guys off, well it’s just about as good as a man can feel, ya know.” But the grind of motels, bad roadside café meals, little sleep, and thousands upon thousands of miles on the road, he could do without.

Falls to run his father’s ranch, while competing at just enough rodeos to make a living. He loved the thrill and skill of rodeo, which comes through in many quotes: “Ridin’ a real good bronc, you know, that throwed a lot of guys off, well it’s just about as good as a man can feel, ya know.” But the grind of motels, bad roadside café meals, little sleep, and thousands upon thousands of miles on the road, he could do without.

“I hated the travel, I still do,” he said in 1973. “I don’t haul worth a damn. I can’t stand sittin’, just sittin’ and looking at the highway.”

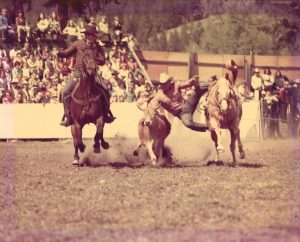

So Kenny came up with a solution and a new way to challenge himself. Most cowboys limited themselves to one event and that was usually all they could handle. Kenny decided to try calf roping and steer wrestling in addition to his signature event bronc riding.

“I just figured that, you know, I didn’t like the travel that much, and if I could rope and bulldog [steer wrestling], get to where I could win, I wouldn’t have to go to as many rodeos.”

In Canada alone during his career Kenny would win five Canadian Pro Rodeo Association saddle bronc championships, as well as one for calf roping, one for team roping, and one for steer wrestling. He would also take home four CPRA all-round champion titles. He often finished in the world’s top-15 in multiple disciplines when it was rare to earn a place once in just one. He would win championships at rodeos across North America including Cheyenne, Calgary, Tucson, San Antonio, Fort Worth, Denver, San Francisco, Pendleton, and Ellensburg. Twice he was recognized with the RCA’s prestigious Bill Linderman Trophy (1967, 1969) as the cowboy who demonstrated the highest level of excellence at both ends of the arena. He was the first Canadian to receive this honour.

In Canada alone during his career Kenny would win five Canadian Pro Rodeo Association saddle bronc championships, as well as one for calf roping, one for team roping, and one for steer wrestling. He would also take home four CPRA all-round champion titles. He often finished in the world’s top-15 in multiple disciplines when it was rare to earn a place once in just one. He would win championships at rodeos across North America including Cheyenne, Calgary, Tucson, San Antonio, Fort Worth, Denver, San Francisco, Pendleton, and Ellensburg. Twice he was recognized with the RCA’s prestigious Bill Linderman Trophy (1967, 1969) as the cowboy who demonstrated the highest level of excellence at both ends of the arena. He was the first Canadian to receive this honour.

Despite all the accolades, like so many other things Kenny rarely talked about his accomplishments, even to his family and friends.

“If I happen to miss a contest, I’ll ask him, ‘How did it go?’ And he’ll say, ‘Fine,’ and that’s all,” his first wife Joyce said to Weekend Magazine‘s Ernest Hillen. “A while later, there’s the trophy on the fridge. Not many people know him, really. He keeps everything to himself.”

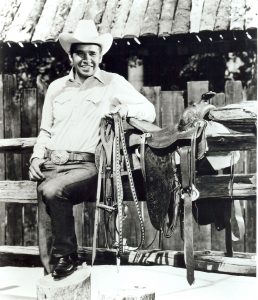

In addition to prize money, at one point it was estimated Kenny won 41 prize saddles, 15 watches, over 100 trophies, and nearly 200 assorted prize buckles, belts, spurs, rifles, boots, hats, silver trays, and even a tea set. He’d reportedly been presented with enough western clothing to outfit his family for life. One year at the Calgary Stampede the biggest problem he faced was how to stuff four trophy saddles into his car already packed tightly with luggage. Stories exist of the unfinished trophy room in his basement being so full of saddles and other awards that there wasn’t any room left to move.

trophies, and nearly 200 assorted prize buckles, belts, spurs, rifles, boots, hats, silver trays, and even a tea set. He’d reportedly been presented with enough western clothing to outfit his family for life. One year at the Calgary Stampede the biggest problem he faced was how to stuff four trophy saddles into his car already packed tightly with luggage. Stories exist of the unfinished trophy room in his basement being so full of saddles and other awards that there wasn’t any room left to move.

Even though he won dozens of saddles over the years, for over a decade he only ever competed on one: his own that he’d had since 1959. That saddle was stolen in 1972 in Seattle and from then on he rode on borrowed saddles.

“A lot of men get a mental block when they lose their saddles,” he said to Hillen. “The confidence goes. I set out to prove different—that I could ride as well on a borrowed saddle.”

Of the roughly 600 pro rodeo cowboys in Canada in 1973, only about half a dozen were good enough to make their full-time living from rodeo. Of the 3000 US pro cowboys, only about 75 could make their living off rodeo. Of those 80 full-time professionals, only a dozen were good enough to compete profitably in more than one event like Kenny. In his best years, he might earn over $15,000.

Of the roughly 600 pro rodeo cowboys in Canada in 1973, only about half a dozen were good enough to make their full-time living from rodeo. Of the 3000 US pro cowboys, only about 75 could make their living off rodeo. Of those 80 full-time professionals, only a dozen were good enough to compete profitably in more than one event like Kenny. In his best years, he might earn over $15,000.

Even then, there were no guarantees for a top cowboy like Kenny to win anything. One time he drove 1300km through the night from Texas to a rodeo in Denver. He paid his $250 entry fee, rode six times, and didn’t win a cent. At his peak, he was on the road 11 months of the year sometimes competing at 60 different rodeos and half of what he earned typically went right back into travel costs. Sometimes his winnings went to hospital expenses for injuries he incurred. He kept costs down in the latter part of his career by travelling the rodeo circuit like a nomad living out of a small GMC camper with his wife Joyce and young son Guy. He often towed behind a two-horse trailer as well, bringing along his own quarter-horses, one for steer wrestling and one for roping.

“We take turns in driving and also looking after Guy,” Joyce explained in Hard Rider, the hour-long NFB doc by Josef Reeve that focused on Kenny’s career. “We had a car and it was hectic. You live in a suitcase and in cafés and we just got sick and tired of getting rotten meals. You know a rat race? It was kinda like living like the city people do.”

“My family’s more important to me than anything, a lot more important than rodeo,” said Kenny. “I like to have Joyce and Guy around all the time. I believe if they had to stay home I wouldn’t rodeo.”

In one sequence in Hard Rider, young Guy can be seen wearing Kenny’s 1967 Linderman Trophy belt buckle.

After winning his third-straight Canadian all-round championship in 1969, Kenny sold his ranch in Okanagan Falls and moved his family to Vernon where they kept a ranch for many years. Sadly, Joyce passed away in 1989. Kenny also lived in Princeton for nearly a decade at the Princeton Exhibition Grounds where the large arena is named in his honour.

After winning his third-straight Canadian all-round championship in 1969, Kenny sold his ranch in Okanagan Falls and moved his family to Vernon where they kept a ranch for many years. Sadly, Joyce passed away in 1989. Kenny also lived in Princeton for nearly a decade at the Princeton Exhibition Grounds where the large arena is named in his honour.

He retired from bronc riding in the early 1970s, but continued to compete in timed events and on the Canadian and American senior pro rodeo circuits. He took the world championship title in calf roping and ribbon roping, as well as the Reserve All-Around Champion Cowboy as late as 2001 at the age of 62. His fame as the greatest Canadian rodeo cowboy of all time often preceded him, but you’d never know it by how Kenny carried himself.

“Everyone knew his name,” his son Guy said. “He didn’t care for the fame at all. He was just doing what he loved.”

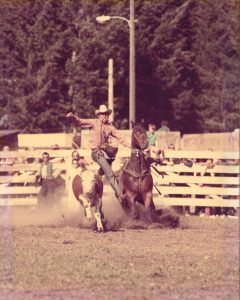

Kenny also gave back to the sport he loved. He became a respected trainer and breeder of his beloved paints. Outside of sitting in the saddle, he seemed to get the most pleasure from passing along little bits of his accumulated rodeo wisdom to the next generation of young cowboys and cowgirls. He sponsored rodeo schools and even converted his own property to host them. Many of the young riders he taught became champions themselves. A few champion riders sought out Kenny to help them refine their technique.

A long-time friend, Bob Lind, told the Simalkameen Spotlight in 2013 that Kenny was always willing to offer help to a young up-and-comer.

“He would never tell you what to do,” said Lind. “He would just simply say, ‘You might try it this way…’ He was always right and it stuck with me.”

“He would never tell you what to do,” said Lind. “He would just simply say, ‘You might try it this way…’ He was always right and it stuck with me.”

Later Kenny remarried and in the late 1990s he and second wife Paula Jo, who was a world-class barrel racer herself, began competing in senior rodeos around Canada. In 2000, the McLeans moved to Hamilton, Montana where they raised horses, ran Paula Jo’s family’s ranch, and began rodeoing full-time on the senior circuit.

“He was a very down-to-earth person, very humble,” Paula Jo told Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine in 2006. “He didn’t come off as a star and was often embarrassed by the attention he received. He was most comfortable on horseback in the arena.”

Sadly, on July 13th, 2002, Kenny was in his saddle on Last Wish, his rope horse, waiting for a senior roping event at a rodeo in Taber, Alberta when his number was called for the final time at the age of 63. He died of a heart attack doing what he loved, rope in hand, 45 years after he saddled up for his first rodeo. Over 800 family, friends, and admirers attended his funeral back in Okanagan Falls watching as Kenny’s prized paint mare was guided into the service, his boots set backwards in the stirrups and his 1962 world championship belt buckle hanging from the saddle horn.

Despite retiring from bronc riding decades earlier, a week before his passing, the world champion bronc rider had one last go.

“You know what was strange,” said Paula Jo, “the weekend before Kenny went to Taber, he was team roping at Standoff. After he roped the steer, it doubled back and the rope went under his mare’s tail. We raised that mare and she had never offered to buck in her life, but that day she clamped her tail and just blew up. Kenny went to spurring her shoulders to get her to lift her tail and she bucked so hard the spectators could see the top of the arena rails under her belly. The crowd went nuts. It was the best bronc ride they had that weekend. Kenny was giggling about it later and said, ‘That sure felt good!’ So he got to have his last bronc ride.”

Later in 2002, Paula Jo rallied from the loss of her beloved husband and coach to win world championships in barrel racing, breakaway roping, ribbon roping, and the all-round championship after many years finishing as runner-up. She dedicated her four-world-title-season to Kenny. Kenny’s son Guy, who still resides in Vernon, named his youngest son Tayber after the town where Kenny passed away.

Later in 2002, Paula Jo rallied from the loss of her beloved husband and coach to win world championships in barrel racing, breakaway roping, ribbon roping, and the all-round championship after many years finishing as runner-up. She dedicated her four-world-title-season to Kenny. Kenny’s son Guy, who still resides in Vernon, named his youngest son Tayber after the town where Kenny passed away.

Mike Puhallo, a well-known cowboy poet from the Okanagan, wrote a tribute to Kenny shortly after his passing:

“Today the west is a little less western.

A great cowboy has been called home

And a hint of sadness hangs in the air wherever true westerners roam.

For this man was the best of the best in the arena or in the hills,

A salty hand in all that he did, a master of those old vaquero skills.

It is still the dream of every young cowboy, who lives by spur and rein,

Just once to hear somebody say: ‘He rides like Kenny McLean.’”

To this day, Kenny McLean holds more records than any Canadian cowboy in “a career distinguished by its volume, versatility and singular consistency” his Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame biography reads, where he was inducted in 2013, 11 years to the day after his death. He is also inducted into the Okanagan Sports Hall of Fame, the Canadian Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame, the Rodeo Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, the Indian Rodeo Hall of Fame, and of course the BC Sports Hall of Fame, where he was the first rodeo cowboy inducted in 1973. His story and artifact collection are prominently featured in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s ‘Circle of Champions’ area within the new Indigenous Sport Gallery. Kenny also received the Order of Canada in 1976 and remains the only rodeo cowboy to receive this honour to this day. Yet how Canada’s greatest rodeo cowboy, who re-wrote the Canadian rodeo record books in the 1960s and early 1970s, is not a member of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame is truly puzzling and should be rectified.

Rodeo Hall of Fame biography reads, where he was inducted in 2013, 11 years to the day after his death. He is also inducted into the Okanagan Sports Hall of Fame, the Canadian Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame, the Rodeo Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, the Indian Rodeo Hall of Fame, and of course the BC Sports Hall of Fame, where he was the first rodeo cowboy inducted in 1973. His story and artifact collection are prominently featured in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s ‘Circle of Champions’ area within the new Indigenous Sport Gallery. Kenny also received the Order of Canada in 1976 and remains the only rodeo cowboy to receive this honour to this day. Yet how Canada’s greatest rodeo cowboy, who re-wrote the Canadian rodeo record books in the 1960s and early 1970s, is not a member of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame is truly puzzling and should be rectified.

Perhaps the most impressive honour bestowed on Kenny, at least visually, was unveiled in 2010. Created by sculptor Hannah Lois to commemorate his life and career, a beautiful, life-size bronze statue of Kenny, calmly sitting back in his characteristic ‘rocking chair’, having the time of his life riding a bucking bronc. The statue stands today at Centennial Park in Okanagan Falls.

We’ll end our look back at the Canadian rodeo legend with one final revealing quote from the great cowboy. Once asked simply why he did rodeo, his answer is a much better summary of his rodeo life than anything this writer could conjure up.

We’ll end our look back at the Canadian rodeo legend with one final revealing quote from the great cowboy. Once asked simply why he did rodeo, his answer is a much better summary of his rodeo life than anything this writer could conjure up.

“I’ve never really thought about it,” Kenny replied. “Rodeo is a job for me. I broke a lot of colts as a youngster, and then I set myself goals: national champ, world champ… You’re conquering, I guess. It’s a challenge. There are horses bucking now that a lot of people can’t ride. If I can ride them, well, then I feel real good.”