A Tribute: You Couldn’t Say No to Jack Farley

April 13, 2021By Jason Beck

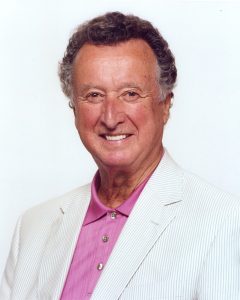

We lost Jack Farley in late March at the age of 88. There were a handful of meaningful online tributes from organizations that he served so faithfully like the BC Lions and the BC Sports Hall of Fame, but it’s a shame his passing didn’t result in more. Jack certainly deserved more. Part of that is due to the restrictions of the pandemic and the shrinking sports media. But the other part of it is Jack probably would have wanted it that way.

BC Lions and the BC Sports Hall of Fame, but it’s a shame his passing didn’t result in more. Jack certainly deserved more. Part of that is due to the restrictions of the pandemic and the shrinking sports media. But the other part of it is Jack probably would have wanted it that way.

Modest to a fault, content to work quietly in the background, and never craving recognition, nevertheless he simply got things done, big things, and in the process built a rock solid reputation and a stalwart career resume that remains among the most respected in the BC sport and business communities.

“He was a very, very good friend for almost fifty years,” said Ron Jones, a former chair of the BC Sports Hall of Fame and among those who knew Jack best. “That Friday [the day Jack passed) was a solemn day. He was a mentor to me. I respected him for his honesty and integrity, all of his dedication, hard work, and singleness of purpose. Jack would always want to know everything about everybody else. He never shared much about Jack.”

Jack Farley may not have had the most recognizable name to the general public, but those who saw his contributions and those who worked with him, knew how significant a figure he truly was. At least three organizations are alive today—the BC Lions, SFU football, and the BC Sports Hall of Fame—largely due to his efforts.

But you’d never hear that from Jack. He wasn’t one to trumpet his accomplishments. Jack was so humble, he’d often keep personal accolades strictly to himself, sometimes not even sharing news of them with his own family.

But you’d never hear that from Jack. He wasn’t one to trumpet his accomplishments. Jack was so humble, he’d often keep personal accolades strictly to himself, sometimes not even sharing news of them with his own family.

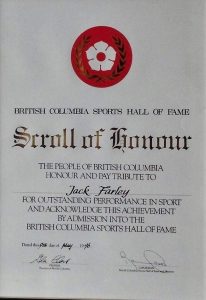

One of my favourite anecdotes about Jack comes from another long-time BC Sports Hall of Fame staff member, former executive director Allison Mailer, and it sums up Jack’s modesty and selflessness perfectly. In 1996, Jack was selected for induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame as a Builder. Jack and his wife Nancy always attended the annual Banquet of Champions induction dinner and this year was no different. But Jack kept the fact he himself was being inducted at this particular Banquet so secret that even Nancy didn’t know until they approached the dinner’s registration desk.

“I just remember him being kind of quiet and not really saying much, just letting this whole moment unfold,” recalled Mailer. “Then Nancy saw his special nametag with those of the other inductees. I was looking at her and looking at Jack and trying to understand what was happening. The process leading up an induction event is at least six months and Nancy had no idea that Jack was being inducted that night. Somehow Jack had managed to keep that secret from her and clearly wanted it to be a surprise. When she found out, there were some tears and it was really, really special.”

That was Jack, always focusing on some other cause, some other project, some other person— never on himself, even on one of the biggest nights of his life.

My biggest takeaway from researching this article—other than that Jack was undoubtedly one of the most well-liked and respected individuals in BC sport, something I already knew first-hand—is that his story has gone largely untold. That is, until now.

I know Jack probably wouldn’t initially approve of an article like this on him, but what better way to pay tribute to one of the most significant figures who worked to preserve the sport heritage of this province through the BC Sports Hall of Fame than by telling his life story in detail.

***

In 2008, I finally pestered Jack enough that he gave in and agreed to sit down for a recorded interview on his career. Although we try to interview each of our new inductees prior to their induction, Jack had somehow avoided the microphone in his induction year despite the fact no inductee was likely as available or more involved in our hall of fame than he was. Again, that was Jack. So we met for an hour in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s old Olympic Inspirations Gallery, a space that existed largely because of his efforts. I thought it was fitting then, and now with hindsight it seems even more so. Before that interview, I already admired Jack but I gained a new appreciation for the man from this sit-down and was surprised on more than a few occasions by details he shared with me.

One came right off the bat when Jack, well-known for his long-time association with West Vancouver where he lived most of his life, described how he was actually born in Kamloops on February 23, 1933.

One came right off the bat when Jack, well-known for his long-time association with West Vancouver where he lived most of his life, described how he was actually born in Kamloops on February 23, 1933.

His father Harold worked as an orderly at Tranquille Sanatorium, a large tuberculosis hospital in Kamloops, and it was there he met Jack’s mother, Gwen, who worked at Tranquille as a nurse, and they married soon after. Harold, who had four children from an earlier marriage, was in his sixties and Gwen in her forties when they had Jack, their only child together.

Jack was still quite young when the Farleys moved to West Vancouver, Jack musing years later that “the black flies drove my parents out” as the reason for their move. They bought a cottage in a part of West Van that could only be accessed by ferry at that time.

Jack had a passion for sports from a young age, playing virtually every sport possible at one time or another.

“Didn’t matter which sport it was, I loved them all,” he said with that characteristic chuckle of his.

At West Vancouver High School, Jack played rugby, basketball, and badminton. To make a few extra bucks, he set pins at the bowling alley. But it was tennis that Jack particularly excelled at. By age 18 in 1951, he was the number-three-ranked junior player in all of BC.

“He loved tennis,” said daughter Karen Farley-Whitaker, one of two children from a previous marriage along with son Brent Farley. “He taught me how to play tennis and we played together, but he never told me that!”

Jack shared that some of his fondest memories were when he was starting out in tennis, working as the assistant groundskeeper at the West Vancouver Tennis Club. They had clay courts and every spring, a group of them would go down to the Capilano River and dig out this beautiful blue clay from the riverbed. They’d pack it back to the tennis club and in May each year spread it out on the courts to dry, then pulverize it, and roll it to refresh the surface.

Jack shared that some of his fondest memories were when he was starting out in tennis, working as the assistant groundskeeper at the West Vancouver Tennis Club. They had clay courts and every spring, a group of them would go down to the Capilano River and dig out this beautiful blue clay from the riverbed. They’d pack it back to the tennis club and in May each year spread it out on the courts to dry, then pulverize it, and roll it to refresh the surface.

After Jack graduated from West Vancouver High School in 1951 (graduating class of just 66 students then), he began working towards his CA, going to school at UBC and articling as a student at Cottrell Forwarding Co. Ltd., a national freight transportation company, while continuing to live at home.

“He was an only child, but he had a group of good buddies in the neighbourhood that he hung around with,” said Karen.

From a young age, Jack loved a good party. Some of the stories of him and his fraternity buddies who for years entered a float in the West Van May Day Parade are legendary. They would liberally partake in ‘Tiddlycove Tea’ and generally have themselves a hoot.

“He loved to party,” recalled Jones. “The bigger the party, the more people there were around, the better he liked it. He was a real people person.”

While Jack was working through school in the early-to-mid-1950s he met his first wife Marlene Ross through mutual friends and they married in 1956.

While Jack was working through school in the early-to-mid-1950s he met his first wife Marlene Ross through mutual friends and they married in 1956.

In the 1950s Jack fell in love with BC Lions football. “He loved his football,” chuckled Karen. When the Lions began play in 1954 at Empire Stadium, Jack and four friends decided to buy tickets together.

“I think the season tickets were $55,” Jack recalled. “There weren’t many touchdowns that year, but we devised a crazy song that the five of us would stand up and sing every time we got a first down.”

Football was already an important consideration in his life by that point. He had one account that he’d calculate income tax for and to do that he’d charge whatever the price of a BC Lions season ticket was that year.

“When season tickets went up to $65 a year, he was charged $65,” Jack chuckled. “That was how I saw BC Lions games in those days.” He remained a Lions season ticket holder for decades, even after becoming a club director. But at first, his involvement with the club was strictly as a spectator.

“I always thought if I had the time or the opportunity, I would like to become a director of the BC Lions and that was sort of my early interest to getting involved with the club officially,” he said.

In the meantime, in 1958 he obtained his degree as a chartered accountant from the Institute of Chartered Accountants of BC. (In 1993, after a distinguished career as a CA, he was elected a Fellow of the Institute.) Jack served as chief financial officer of Cottrell Forwarding and later became a partner.

In the meantime, in 1958 he obtained his degree as a chartered accountant from the Institute of Chartered Accountants of BC. (In 1993, after a distinguished career as a CA, he was elected a Fellow of the Institute.) Jack served as chief financial officer of Cottrell Forwarding and later became a partner.

“That’s where he started out, doing accounting there,” said Karen. “Francis Cottrell, the owner, he was like a dad to my dad.”

Even as his accounting and business career picked up speed, Jack maintained his interest in football. In the mid-1960s, he remembered doing the audit for Dueck on Broadway (now Dueck on Marine) and was working on a Saturday at their office while quietly listening to the Grey Cup game on a small single-speaker radio he’d smuggled in.

“L.D. Dueck caught me and said, ‘What’s the score?’” recalled Jack chuckling. “I told him and he came over, sat down, and listened to the game with me.”

***

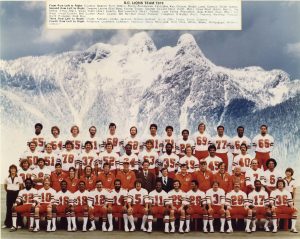

By the 1970s, Jack was ready to become more involved and move beyond simply attending Lions games. He wrote a letter to Chunky Woodward, chair of the BC Lions board advisory committee, expressing his interest to join the club as a director. Chunky sent a polite reply back that no openings were available. By 1974 though, the Lions, in rough shape financially and with a newly-resigned treasurer, were singing a different tune. They needed someone with a solid financial background on their board. Farley fit the bill.

“Out of the blue, Chunky phones me: ‘You still interested in joining the BC Lions?’” Jack chuckled later. “Of course I came on board.”

“Out of the blue, Chunky phones me: ‘You still interested in joining the BC Lions?’” Jack chuckled later. “Of course I came on board.”

It was one of the best financial decisions the Lions ever made. Jack had no idea the mess the Lions found themselves in, but he learned quick enough. At his very first director’s meeting, he had been instructed to pick up Lions president Bill McEwen at the seaplane terminal after he’d flown in from Victoria. On the drive to the meeting, McEwen indicated that he wasn’t happy with GM Jackie Parker and coach Eagle Keys. By the end of the meeting both men were fired and Bobby Ackles was hired as the Lions new GM.

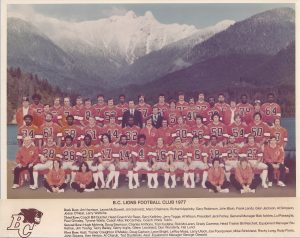

No one knew it at the time, but the arrival of Jack and the promotion of Bobby was a critical turning point for the franchise. They became the two key figures in righting the Lions fortunes on the field and in the bank statements. More than that, they became close friends for life and worked seamlessly in tandem.

They went to work beginning in 1975, the first of two years Jack served as team treasurer and then two more as team president in 1977-78. Some creative financing was needed to get the club on track after posting a deficit of $300,000 in 1974.

They went to work beginning in 1975, the first of two years Jack served as team treasurer and then two more as team president in 1977-78. Some creative financing was needed to get the club on track after posting a deficit of $300,000 in 1974.

“That was a lot of money in those days,” Jack said. So they approached the CFL for help through a loan, but the league turned them down.

“We decided to do a debenture issue of $300,000,” he explained. “We wanted to see if the community was ready to come to the plate and buy into this debenture plan of multiples of $50, $200, $1000 and so on. Vic Spencer stepped up first and gave us a cheque for $5000 to kick off the campaign. Within about two or three weeks, we had about $200,000 in the kitty and then about two months in, we sold out.”

At the same time, Jack and Bobby approached PNE president Erwin Swangard about working out a rental reduction at Empire Stadium of $250,000 over a period of three years, but it was subject to the Lions having matching funds. What Swangard didn’t know, is that Jack and Bobby had already obtained the necessary matching $250,000 from Labatt’s. Well played, Farley.

At the same time, Jack and Bobby approached PNE president Erwin Swangard about working out a rental reduction at Empire Stadium of $250,000 over a period of three years, but it was subject to the Lions having matching funds. What Swangard didn’t know, is that Jack and Bobby had already obtained the necessary matching $250,000 from Labatt’s. Well played, Farley.

“So that gave us $800,000 and that carried the club for the next three or four years,” Jack grinned. “That was the start of something very special there.”

Long story short, it saved the club, holding off any immediate financial pressures, while putting the Lions in a position to work toward a new downtown stadium, which ultimately arrived in 1983 in the form of BC Place. Jack played a supporting role in arranging that too of course.

The Lions current Surrey offices and practice facility? Jack supported his friend Ron Jones on that as well, who had a deal arranged with Surrey mayor Don Ross. In order to make that happen they needed extra funds to bridge the gap before the move to BC Place and the resulting increased revenues. So they decided to do another debenture issue in 1982.

“This one we cranked it up,” Jack recalled. “There were $25,000 per debenture and you had the choice of four outstanding seats at Lions games in the new stadium. We raised $1.2 million.”

“This one we cranked it up,” Jack recalled. “There were $25,000 per debenture and you had the choice of four outstanding seats at Lions games in the new stadium. We raised $1.2 million.”

The sod on the new practice facility was turned in early 1983 and the club was debt-free by 1984.

Bob Ackles told me in the mid-2000s that he always felt the one of the prime reasons the Lions were still alive today was because of Jack. He felt it was a crime that few knew that. He reiterated that point in his 2007 book The Water Boy: “Jack was the former director and president most instrumental in turning the Lions franchise around in the wake of the financial disaster of the mid-1970s.”

When I interviewed Jack in 2008, it was just a few months since Bobby’s sudden passing that rocked Canadian football. The loss of his friend was still raw. I asked him what the biggest disappointment of his career had been. He paused and then, his voice breaking, almost whispered, “Losing Bobby… Still can’t get over it…”

***

Jack began attending CFL meetings with Bobby as early as 1975 and only became more involved at the league level when he became Lions president. The timing of his second year in this role also corresponded with Jack taking on an even greater role that resulted in one of his proudest accomplishments.

At that time, Jake Gaudaur Jr. served as CFL commissioner, but the league was also governed by the board of governors, which rotated its’ president every year to one of the presidents of the nine CFL teams. Jack’s term as Lions president lined up with this rotation perfectly and he became the board of governors president in 1978. His goal from the beginning was to unite the league.

At that time the CFL’s eastern teams were led by private ownership groups, while the western clubs were publicly owned, which resulted in widely varying philosophies and needs. More than that, the league was still divided into Western and Eastern Football Conferences each with their own separate by-laws and constitutions. Jack realized at the league meetings each conference met separately the day before they both gathered as a group and spent that time plotting how to get a leg up on the other side.

“I could see it was pulling the league apart,” Jack said. “Quite often both sides were inflexible at the league meetings—it was east versus west. We needed to work together.”

He proposed early in his term as league president his vision of “A new CFL—all for one and one for all” as one Canadian Press headline put it in February 1978. Jack began working behind the scenes. He was soon able to get the western teams to agree to abandon the Western Football Conference if the East would abandon their conference. His tenure as CFL president ended, but the next year in 1979 he became president of the Western Football Conference and he was able to continue these discussions. After Jack’s term in that role ended, Saskatchewan’s Bruce Cowie, who succeeded Jack, was able to finalize the arrangement that united the two sides into one unified league, which it remains to this day.

“So that’s my legacy as far as the CFL is concerned,” Jack beamed, summing up the story. “That was just great.”

***

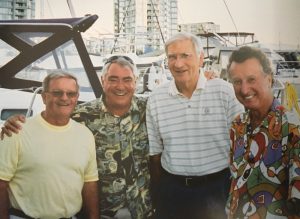

Ackles wasn’t the only close friend Jack made in his time with the Lions. Ron Jones and Norm Fieldgate joined the Lions board of directors shortly after Jack. They quickly became like the Three Amigos, when not running and/or saving the Lions, they had season tickets next to one another in BC Place, their families spent time together, they travelled, and often did business with one another. Quick example? When Norm started a business called “NFL” (short for Norm Fieldgate Limited) importing auto parts, he worked with Jack’s company, Cottrell Forwarding, to bring in the parts from off-shore suppliers.

“The three of us became buddies,” said Jones. “Jack and Norm and I spent a lot of time together. We had wonderful times. We used to vacation together. We spent a lot of time in a lot of different places in the world together. Never had bad words between the three of us. And we attracted a lot of good people around us too. This last year has been a sad year. I lost two of my best friends…that hurts a lot.”

“The three of us became buddies,” said Jones. “Jack and Norm and I spent a lot of time together. We had wonderful times. We used to vacation together. We spent a lot of time in a lot of different places in the world together. Never had bad words between the three of us. And we attracted a lot of good people around us too. This last year has been a sad year. I lost two of my best friends…that hurts a lot.”

Sadly, Fieldgate passed away in early March 2020, a little over a year before Jack. Two of the Three Amigos are gone now, but Jones quickly shifts back to happier memories.

“Jack didn’t know the phrase ‘couldn’t make it happen,’” Jones laughed. “He’d just keep pressing. He always leaned on me because when he asked me to do something I never wanted to let him down. I always enjoyed Jack’s company so much I could never say no to him. I guess he knew that because he kept asking me to do stuff and I always delivered everything he asked. And through that we got to spend a lot of time together.”

There was one time however when Jones was able to say no to Jack and hold him off, at least for a little while.

“He had me targeted for the next president of the Lions, but I didn’t want to do it,” Jones remembered. “So Paul Higgins served as president, but when Paul was finished, Jack still had his oar in the water and he came after me again. And I still said no! He came to my office and he said, ‘I’m not leaving your office until you give me a yes!’ He was determined and so I finally said yes. I ended up enjoying being Lions president. At the end of the day, I was really happy he asked me to do that. Subsequently the same thing happened at the BC Sports Hall of Fame.”

Jones was Lions president in 1983 when according to club by-laws Jack was required to retire from the Lions board of directors after nine years. To honour his contributions, the Lions retired jersey number 83, a unique tribute for someone who never stepped foot on the gridiron. Jones came up with the idea for his close friend.

“I thought for all his contributions that I witnessed over all his years and him just leaving wasn’t enough,” explained Jones. “His contribution was so enormous that I likened it to a star player and on an only volunteer basis. I told Ackles what my thoughts were and he agreed.”

“That was a total surprise,” said Jack. “I don’t think that’s ever been done in professional sport before.”

Jack departed the board as everything was looking up. They had the players, the coaching, and management in place. Solid board leadership and financial stability. A new training facility. A brand-new world-class stadium to call home. Crowds of 50,000+ screaming fans were common. They were hosting and making it to Grey Cups, including in 1985 when the Lions won their second championship in club history. Jack and Bobby and those they brought in around them had completely turned the Lions around in just a few short years.

“Everything was hunky-dory until Bobby got the phone call from Tex Schramm in Dallas to join the Cowboys in 1986,” Jack said. “Unfortunately the Lions floundered after that.”

By the late 1980s, the Lions financial situation appeared grim once again. Crowd sizes had cratered at home games and the team was drowning in red ink. Fieldgate was Lions president by then and he tasked an ex-presidents committee of Jack, Jones, and Paul Higgins with writing a report on the club’s financial viability. Jack’s committee determined the only way out for the community-owned team since 1954 was sale to a private owner. They worked to smooth this transition and it led to a rocky decade before David Braley’s arrival in 1997 calmed the waters once again.

***

When Jack stepped off the Lions board in 1983, he remained more involved in football than ever before. After saving the Lions on at least two occasions already, he already had a reputation as a miracle worker. When people learn you’ve got a knack for raising funds, suddenly you find yourself in great demand and Jack seemed to go from one fundraising project to the next. He was a master at it and people trusted him. As legendary Canucks broadcaster Jim Robson once said, “Who could say no to Jack Farley?!”

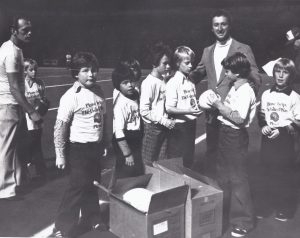

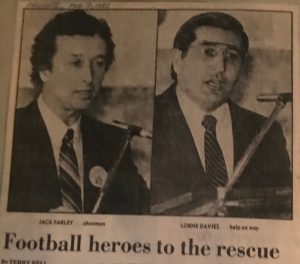

In 1982, Simon Fraser University announced that they planned to eliminate men’s football from the university’s athletic program due to an accumulation of $1.5 million in debt. Lorne Davies, SFU’s athletic director, phoned Jack for help. Without hesitation, Jack agreed to assist, serving as chair of the newly-formed SFU Football Fund Program with a goal of raising a quarter-million-dollar endowment fund that could grow interest and sustain the football program long-term. At the group’s first meeting, they raised $50,000 which got the ball rolling.

In 1982, Simon Fraser University announced that they planned to eliminate men’s football from the university’s athletic program due to an accumulation of $1.5 million in debt. Lorne Davies, SFU’s athletic director, phoned Jack for help. Without hesitation, Jack agreed to assist, serving as chair of the newly-formed SFU Football Fund Program with a goal of raising a quarter-million-dollar endowment fund that could grow interest and sustain the football program long-term. At the group’s first meeting, they raised $50,000 which got the ball rolling.

“After two or three months, we did it,” he said. The SFU football program continues to operate to this day. Jack was awarded the Fred H. Dietrich Memorial Award by SFU for his efforts. He was also asked to join SFU’s board of governors.

Not long after, SFU was exploring the idea of building a downtown Vancouver campus and other major improvements, but wasn’t sure if support in the community existed for the project. SFU president Bill Saywell talked Jack into becoming executive director of the ‘Bridge to the Future’ campaign. He stepped down off the SFU board of governors to do so and spent the next six months undertaking a feasibility study in which he interviewed alumni, the business community, and contributors. An initially large ‘wish list’ was whittled down to $35 million in improvements, which Jack presented in a report. He stayed on helping this project along for three years, organizing fundraising representatives for each province to make it a truly national campaign.

“Our target was the $35 million,” he recalled. “By golly, we raised over $60 million bucks! So it was extremely successful and the first time the business community was really involved with SFU. And Simon Fraser’s never really looked back.”

***

Around the same time as Jack’s initial involvement with SFU, he became involved with an event he’d been attending since his early twenties: the Grey Cup. Jack was there in 1955 at the very first Grey Cup held in Vancouver (first in western Canada too), standing in the mud with his pals on the hill in Empire Stadium’s north end zone in the Woodward’s Quarterback Club section. They watched Edmonton’s Jackie Parker, Normie Kwong, and Johnny Bright run away from Montreal’s gun-slinging Sam Etcheverry, who passed for over 500 yards in a losing cause. Jack was hooked on Grey Cup fever from then on.

Promoting the 1983 Grey Cup was an easy fit for him. The newly-built BC Place Stadium was hosting Vancouver’s first Grey Cup game in nine years and who better to ensure the big game was a smashing success. He loved the party that was Grey Cup week and rallied his faithful group of supporters. By that point he was used to running the off-field dinner entertainment at Lions training camps around BC and this was much the same thing but on a larger scale.

“He was always directing traffic,” said Jones. “And gathering people around to help him do it.”

Jack served as general chairman of both the 1983 and 1986 Grey Cup Festival committees, each of which sold out with over 59,000 fans in attendance. He also later served as a key director for the 1994 and 1999 Grey Cup Festivals in Vancouver. Some say Jack’s infectious enthusiasm for the game was all that was needed to sell tickets. He could often be found at community events in his characteristic ‘Captain Vancouver’ costume promoting and selling with that characteristic Farley smile.

One of his more memorable appearances was at the annual Nanaimo Bathtub Races in 1983, where Jack as Captain Vancouver teamed with Nanaimo mayor Frank Ney dressed as a sword-toting pirate in the double-tub paddle sternwheeler mayor’s race. Jack helped—some said he carried—Ney to his first-ever victory in the bathtub races in 17 years trying.

One of his more memorable appearances was at the annual Nanaimo Bathtub Races in 1983, where Jack as Captain Vancouver teamed with Nanaimo mayor Frank Ney dressed as a sword-toting pirate in the double-tub paddle sternwheeler mayor’s race. Jack helped—some said he carried—Ney to his first-ever victory in the bathtub races in 17 years trying.

“His contributions made a real difference,” said Glen Ringdal, who worked with Jack with both the Lions and the BC Sports Hall of Fame. “And nobody could celebrate a Grey Cup like Jack.”

Former long-time BC Lions broadcaster J. Paul McConnell remembered Jack as someone who could bring people together for big events: “He led quite the group—always there, everywhere, keeping the team going through the tough times. A great man—to be sure.”

***

In 1982 former Lions player Tom Hinton (a future BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee in 1992), convinced Jack to join him on the Hall of Fame’s board. When I asked Jack to sum up his time with the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 2008, in typical understated fashion he said simply, “It’s been a great association.”

You could say that, yeah.

Over the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s 55-year history, there have been few individuals who played more critical roles than Jack in elevating the Hall’s mandate and profile while also ensuring the organization’s survival. From 1982 until 2006 he served the longest uninterrupted term of any Hall of Fame trustee in our organization’s history. During that 24-year period, he also served as the chair of the BC Sports Hall of Fame from 1992-93. Later, he was one of the key founders of the BC Sports Hall of Fame Foundation and stayed involved with this group for many years.

But that really only begins to scratch the surface of Jack’s Hall of Fame contributions.

It started with encouraging others to join him on the Hall of Fame board: soon close friends Jones and Fieldgate were right there beside him. Later he supported a couple generations of Hall staff including former executive director Don Taylor, even helping Taylor study for his Masters degree by quizzing him on financial questions.

“He was definitely a big supporter of the BC Sports Hall and sports in BC,” said former Hall of Fame chair Anna Nyarady. “He always had a positive attitude and a smile on his face.”

“An incredible man,” agreed another former Hall chair Bill Maclagan. “Amazing supporter of the Hall. He did not just talk. He was always there for us.”

“An incredible man,” agreed another former Hall chair Bill Maclagan. “Amazing supporter of the Hall. He did not just talk. He was always there for us.”

“Maybe one of Jack’s strongest legacies was the exceptional people he was able to bring to the BC Sports Hall of Fame in various roles as volunteers,” said former executive director Allison Mailer, who considered Jack a mentor. “Really forward thinking leadership. It was never about Jack Farley. It was about the organization or project or the team of people making something happen. It was never about him. It was about a goal that he believed in that could be achieved and that’s what motivated him. It was easy for others to get behind that.”

His leadership and influence touched everyone involved with the Hall.

“He was certainly one of the main drivers of the Hall of Fame when I came on board,” recalled former Hall of Fame chair Dann Konkin. “He was always very articulate. Very soft-spoken. But incredibly visionary in terms of seeing what he could do out there. And Jack was never a gentleman who’d go around and tell people what he did. He’d have that quiet confidence about him. He went out there, did his job, helped groups out, and you just didn’t know about it.”

One of the best examples was how he approached ticket sales for the annual Banquet of Champions induction dinner. Jack led the annual sales drive for years. After doing it for the Lions and the Grey Cups, he was a master at it. His secret for success was simple.

“He was one of those people who led by example,” Mailer said. “In the Banquet meetings he would take the potential guest list and divide it up among the committee members. Then he would come into the Hall of Fame, use our phones in the board room, and just make his phone calls and sell, sell, sell, getting people to attend and support the Banquet.

“Never a leader that would be ‘what have you done lately?’ It was ‘I’ve made my page of phone calls, what have you done?’ At that time not one person would come into those meetings not having made those calls because you knew Jack would have made his. He wasn’t a big vocal leader, but quietly got the work done. Other people would see his example and come along for the ride.”

He was always thinking of ways to honour others. Over the years I lost count of how many athletes and coaches and teams Jack nominated to the BC Sports Hall of Fame, many of whom were selected for induction. He did his homework and his nominations were always first-class.

It was also the little things. I remember Jack always going out of his way to give Audrey Williams a ride to committee meetings they attended together. Or checking in on Honoured Members who weren’t well. When we sat down for the interview in 2008, he told me how he’d been visiting ailing Vancouver media legends Ted Reynolds and Jim Kearney at their respective care homes. When he realized they were nearby one another, he organized a visit where he wheeled Jim in his wheelchair over to Ted’s facility, so the two old colleagues could have one final visit.

“They had a great meeting a week and a half before Jim died,” Jack said.

***

Walk up to the BC Sports Hall of Fame today and there are still vestiges of the Farley fundraising wizardry all around you and most aren’t even aware of it.

That magnificent statue of the great Vancouver sprinter Percy Williams, double Olympic gold medalist in 1928? The BC Amateur Sports Council had the idea, but no money to make it happen. They approached Jack and voila, he had the money in short order. He even found the company who donated the boulder on which ‘Peerless Percy’ is perched.

That magnificent statue of the great Vancouver sprinter Percy Williams, double Olympic gold medalist in 1928? The BC Amateur Sports Council had the idea, but no money to make it happen. They approached Jack and voila, he had the money in short order. He even found the company who donated the boulder on which ‘Peerless Percy’ is perched.

But the biggest monument to Jack’s work? It’s the fact the BC Sports Hall of Fame is at BC Place and still in operation today.

By the mid-1980s, the opportunity arose for the Hall of Fame to move from the BC Building at the PNE to BC Place. The Hall’s curator and executive director at the time, Bob Graham, came up with an interactive, dynamic design and all that was needed now was to raise the money for the move and building costs.

“We had an executive committee meeting,” recalled Jack. “Gerald McGavin, the Hall’s chair at the time, said, ‘Who’s going to take this on?’ Deathly silence. Finally Farley puts his hand up and says, ‘Ok, let’s do it.’ I thought to myself, ‘Aw hell, if I can do it for Simon Fraser, for the Lions, I can do it for the Hall of Fame.”

A capital campaign was started and Jack donated countless volunteer hours spearheading the cause. He worked with Ron Jones to obtain the first $1 million in funding from the provincial government through a Go BC grant, one of the first awarded to a BC organization.

“That was our starting point,” he said.

They then went after the federal government for matching funds and Mary Collins, North Vancouver MP, became their key contact. After about a year of lobbying, the Hall received another $1 million from the feds. At the same time Jack was able to get $300,000 from the City of Vancouver. Then they went to the public in a very targeted campaign. The Hall’s new design created by Graham featured ‘Decade Galleries’ focusing on the development of BC sport one decade at a time from the 1850s to the present.

“We looked into each decade for any trustees or Honoured Members who had any connections to that decade and went to them,” explained Jack. “We decided to go after $50,000 per decade and some of the larger ones $100,000. The first person we went to was Peter Bentley for the 1930s and his pal Ron Cliff for the 1970s. It took a while, but we gave presentations everywhere we could and gradually we convinced people they were buying into something meaningful to them that happened in that particular decade.”

“We looked into each decade for any trustees or Honoured Members who had any connections to that decade and went to them,” explained Jack. “We decided to go after $50,000 per decade and some of the larger ones $100,000. The first person we went to was Peter Bentley for the 1930s and his pal Ron Cliff for the 1970s. It took a while, but we gave presentations everywhere we could and gradually we convinced people they were buying into something meaningful to them that happened in that particular decade.”

The Hall of Fame’s first phase opened in 1992 and a second phase in 1994. The third and final phase proved the toughest. Project costs had risen beyond the initial amount fundraised putting the completion of the new Hall of Fame in doubt—and the organization’s very financial stability at risk.

“The costs were catching up to us and we needed another million dollars, so that’s when we came up with ‘The Finish Line Team,’” recalled Jack.

What happened next is one of the great moments in the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s history. Jack held a closed door meeting inviting a select group of friends and colleagues who had the means to support the Hall of Fame in a significant way: Peter Bentley and Ron Cliff again, Jack Diamond, Erwin Singh Braich, the Griffiths Family, Milan Ilich and a handful of others. He called on them to join him, to push this Hall of Fame project over the finish line. He asked each person there to donate $100,000 to raise the final $1 million needed to complete the project and set the Hall’s financial issues in line. And to convince them he was serious, Jack wrote the first $100,000 cheque himself on the spot and placed it down on the table in front of him. By the end of the short meeting, Jack had the $1 million the Hall needed.

“That completed it,” he recalled proudly.

“I’d been in lot of fundraising meetings before that one,” said Bob Graham, “but I’ve never seen anything like that before or since. Jack was one of a kind.”

That perhaps more than any other anecdote illustrates the high esteem Jack was held in the sport community and what he would do for this organization. The BC Sports Hall of Fame was able to proceed and complete its new 20,000-square-foot layout, a design that influenced sports halls across the continent for the next decade. In total Jack had helped raise over $5 million to relocate, design, and build the new BC Sports Hall of Fame.

“I don’t know what it is, but I guess I’m tenacious,” he summed up. “I like to succeed. All the organizations I helped, they’re all great. You get a feeling for them and get good people around you, you can go and do it.”

***

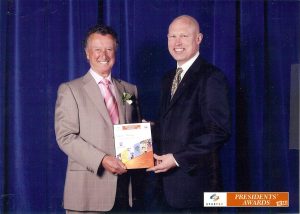

Hardly surprising, but Jack received several honours later in life that recognized his contributions to sport and the community. In 2003, he was a charter member of the BC Lions Wall of Fame. In 2006, he received the Sport BC President’s Award, and in 2008, he was the recipient of a BC Community Achievement Award. In 2012, upon his induction into the BC Football Hall of Fame he received the CFL Bob Ackles Award. In 2015, David Johnston, the Governor General of Canada, awarded Jack the Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers.

There is one glaring omission in Jack’s career trophy case though. I never call out other halls of fame, but how Jack Farley is not inducted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame I don’t for the life of me know, but perhaps this article will start those wheels in motion to rectify that.

There is one glaring omission in Jack’s career trophy case though. I never call out other halls of fame, but how Jack Farley is not inducted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame I don’t for the life of me know, but perhaps this article will start those wheels in motion to rectify that.

Two other awards held particularly special meaning for him.

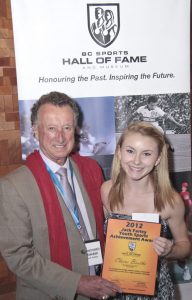

For over twenty years, the Jack Farley Youth Sports Achievement Award scholarships were given by the BC Sports Hall of Fame to two graduating BC high school students. These scholarships went to young budding student-athletes who occasionally turned into future Olympians and world champions. Named in Jack’s honour, many thought Jack initiated and funded the award himself. But the truth couldn’t be further from that. It was actually created and funded as a tribute to Jack by long-time friend Norm Fieldgate.

“I remember asking Norm why he did that,” said Dann Konkin, Norm’s son-in-law. “He said, ‘Because Jack has given so much to the BC Sports Hall of Fame and the BC Lions, I felt he deserved some kind of recognition.’ It was a pure tribute to Jack because he helped the Hall of Fame in so many ways. He was an icon there.”

“I remember asking Norm why he did that,” said Dann Konkin, Norm’s son-in-law. “He said, ‘Because Jack has given so much to the BC Sports Hall of Fame and the BC Lions, I felt he deserved some kind of recognition.’ It was a pure tribute to Jack because he helped the Hall of Fame in so many ways. He was an icon there.”

Later it was learned Norm was also returning a favour to his old friend. Norm’s daughter Carey explained: “You know why my dad did that? Because back in 1974 Jack was instrumental in renaming the CFL’s Western Conference defensive player of the year award in my dad’s name. The Norm Fieldgate Trophy is still awarded today.”

And of course there was Jack’s induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 1996, one of his proudest accomplishments.

“It’s a helluva tribute,” he said in 2008. “It’s something that I never expected, never in a thousand years, never expected it.”

A lot of people say things like that all the time, but the crazy thing is after everything he did, you know Jack truly meant that.

***

The BC Sports Hall of Fame held a special place in Jack’s heart, of that there is no doubt. I sensed it when we sat down for that interview in 2008. I saw it later when fellow long-time BC Sports Hall of Fame staff member Barbara Chu and I visited Jack at his West Vancouver care home and presented him with his new Honoured Member pin. Jack wasn’t well, but his face just lit up.

The BC Sports Hall of Fame held a special place in Jack’s heart, of that there is no doubt. I sensed it when we sat down for that interview in 2008. I saw it later when fellow long-time BC Sports Hall of Fame staff member Barbara Chu and I visited Jack at his West Vancouver care home and presented him with his new Honoured Member pin. Jack wasn’t well, but his face just lit up.

The BC Sports Hall of Fame was home for him. Home to friends. Home to treasured sports memories from his youth and from his own career. Home to some of the happiest moments and times of his life. Jack was a regular at virtually every Hall of Fame event big or small for decades. He remained a trusted advisor that current staff and board members could turn to for a few precious pearls of wisdom.

For years after stepping off the Hall’s board, he regularly stopped in to check on our staff, to see what new projects were in the works. It would be a random Tuesday afternoon and Jack would walk in the front door, smiling that warm smile of his and spreading that positive ‘can-do’ spirit that marked every conversation I can recall with him.

Always encouraging and supportive, the depth that Jack cared about this Hall of Fame and everyone who is part of it is hard to imagine.

But when you were around Jack, it simply shone through.