Carla Qualtrough: Canada’s Minister of Sport – 2023 Inductee Spotlight

October 31, 2023By Jason Beck

With October being Women’s History Month in Canada what better time than now to look back at the life and career of one of the most influential and respected women in Canadian sport over the last 25 years. The Honourable Carla Qualtrough, currently the Minister of Sport and Physical Activity and Member of Parliament for Delta, is someone who has both made and changed history for women and para sport in this country. A lifelong love of sport forged when she was young has shaped every challenge and opportunity she has encountered along the way.

respected women in Canadian sport over the last 25 years. The Honourable Carla Qualtrough, currently the Minister of Sport and Physical Activity and Member of Parliament for Delta, is someone who has both made and changed history for women and para sport in this country. A lifelong love of sport forged when she was young has shaped every challenge and opportunity she has encountered along the way.

Born in Calgary, Alberta, Carla’s family moved to Langley when she was four years old. She grew up in the Brookswood area of Langley eventually graduating from Brookswood Secondary. Sport was a constant in the Qualtrough household growing up.

“I was born into a family of sport,” Carla said in a phone interview with the BC Sports Hall of Fame earlier this year. “We did every sport imaginable in my family. It was a language we all spoke and we were all full-fledged members of that. That’s how we communicated as a family. I loved sport. Whatever sport you offered me, I wanted to try it, play it, be good at it, get better at it, and then win at it.”

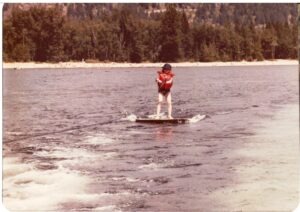

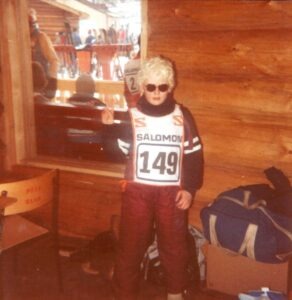

Carla was water skiing by age two and she also participated in downhill skiing, soccer, swimming, curling, and softball growing up. Which isn’t uncommon for an active kid until you consider that Carla was born legally blind. Her father and mother decided very early on that Carla’s vision impairment would not stop her from being involved in sport.

Carla was water skiing by age two and she also participated in downhill skiing, soccer, swimming, curling, and softball growing up. Which isn’t uncommon for an active kid until you consider that Carla was born legally blind. Her father and mother decided very early on that Carla’s vision impairment would not stop her from being involved in sport.

“In fact, my dad felt that was one way I could level the playing field by being very good at sport,” she explained. “He spent a lot of my childhood accommodating my disability. Figuring out how I could still play sports even though I couldn’t see very well.”

Carla’s dad would routinely invite her soccer teammates over and in the backyard they’d work on how they could pass Carla the ball so she could see it. She was often the pitcher on her softball team, so they made sure the catcher threw the ball to her younger brother playing shortstop and then he would gently throw the ball to Carla.

they could pass Carla the ball so she could see it. She was often the pitcher on her softball team, so they made sure the catcher threw the ball to her younger brother playing shortstop and then he would gently throw the ball to Carla.

“We just did a lot of accommodation I guess I would call it now,” she said. “The hard part for me was when I got to a certain point and it wasn’t as easy to self-accommodate. Like, it got fast, it got dangerous. I stopped winning and began to be frustrated because it didn’t matter what we did or how much I practiced, the fact that I couldn’t see very well kind of caught up with me I guess.”

Around age 11 or 12, Carla was introduced to para sport and blind sports and began going to camps and competitions.

“It was a revelation,” she exclaimed. “Everyone was like me and I didn’t need to accommodate. The playing field was levelled. I was included from the start. I only competed against people with my level of sight and it just felt more fair. I felt more included.”

“It was a revelation,” she exclaimed. “Everyone was like me and I didn’t need to accommodate. The playing field was levelled. I was included from the start. I only competed against people with my level of sight and it just felt more fair. I felt more included.”

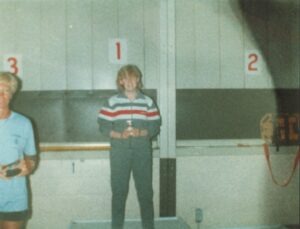

She swam for the Langley Flippers and competed at the BC Winter Games in downhill skiing. Like most Canadians in the mid-1980s, she admired Rick Hansen, but Carla didn’t look up to many other athletes because “there weren’t any like me. I couldn’t name one blind athlete. I didn’t see leaders or high-performance athletes that looked like me.”

By age 14, she chose to focus on swimming as her primary sport.

“I’ve very candidly told people, my life could have gone in a whole bunch of different directions,” she said. “If I hadn’t found swimming, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I’m so grateful that I found that community, that sport, that lifetime love. It really changed my life.”

Her favourite event was the 100m butterfly, but her strongest event was actually the breaststroke, which became interesting when she began competing for Canada later on.

“There was always negotiations,” she chuckled. “‘We’ll let you do the fly if you do breast.’”

Carla progressed from winning provincial competitions to claiming national championships and her times qualified her to compete internationally. In 1986 she was selected to compete for Canada at the first World Youth Games for athletes with a disability in Nottingham, England. Having competed mostly within the blind sports world, this multi-sport, multi-disability competition was a first for her. Carla found herself on the Canadian team that featured other future para sport legends like Jeff Adams and Chantal Peticlerc.

“It was fantastic,” Carla recalled. “We were a bunch of young kids. I was 14 turning 15, super young. On my own in Nottingham, making friends, and just seeing the world. And competing. It was just wonderful.”

“It was fantastic,” Carla recalled. “We were a bunch of young kids. I was 14 turning 15, super young. On my own in Nottingham, making friends, and just seeing the world. And competing. It was just wonderful.”

Two years later Carla was competing at the 1988 Summer Paralympics in Seoul, South Korea, part of an early generation of Canadian para sport athletes who had to blaze their own trails often without the benefit of heroes they could readily identify with. Carla found herself among not just Peticlerc and Adams, but Coquitlam’s Ljiljana Ljubisic and Nanaimo’s Michael Edgson, a fellow swimmer, lifelong close friend, and 2012 BC Sports Hall of Fame inductee.

“There were obviously people that came before me and I’m not disrespecting them, but there was this wave in the late 1980s of Paralympic success stories.”

stories.”

Carla was definitely one of them. Turning 17 the day of the Games Opening Ceremony—“I thought it was very nice of them to throw me such a big party!”—she finished fourth in three individual event finals before helping the Canadian 4x100m medley relay team (B1-3 classification) to a bronze medal.

“It was pretty exciting,” she recalled. “It was my first time on the Paralympic podium. The flag, the uniform—it was pretty magical. It was also pretty overwhelming I would say because I was 17 and now what do you do? You’re third in the world at something, you know, what’s next? It was, well, you do it again! That’s what’s next! [laughs]”

So she did do it again, several times over actually. At the 1990 World Championships and Games for the Disabled in Assen, Netherlands, she swam to two individual bronze medals and four silver medals on Canadian relay teams for an impressive six-medal haul.

So she did do it again, several times over actually. At the 1990 World Championships and Games for the Disabled in Assen, Netherlands, she swam to two individual bronze medals and four silver medals on Canadian relay teams for an impressive six-medal haul.

“That was a great Games for me where I was personally, my age and my experience, and it was super fun. We swam hard. We played hard. We did everything 19 and 20-year-olds do when you’re on a swim team. I have great memories of that event.”

By that point she had been training for nearly ten years, much of it swimming 11 times a week between meets and training resulting in a lot of her teenage years spent at the pool. She was beginning to feel an inclination to retire but committed to swimming through the next Paralympics in Barcelona.

In 1989 Carla had graduated from high school and spent a couple of years at Simon Fraser University swimming on the varsity team. Halfway through completing her undergraduate degree, she transferred to the University of Ottawa and swam there too. She finished her undergraduate degree the same year she competed at the Barcelona Paralympics. By that point para sports in Canada were transitioning to a better high-performance model, but still not where they needed to be. But at least the travel and other costs for athletes on the Canadian Paralympic team were all covered this time like the Canadian Olympic team. Four years earlier, Carla recalled that her parents had to pay for her Canadian uniform and her flight to South Korea to compete at the Games. Langley actually held a big fundraiser to pay for Carla’s training and travel to go. They ended up raising enough money that Carla’s mom was also able to accompany her. By 1992, the Canadian Paralympic team was funded enough to cover these costs like the Olympic team. It was just one of many small improvements Carla witnessed during her competitive career.

on the varsity team. Halfway through completing her undergraduate degree, she transferred to the University of Ottawa and swam there too. She finished her undergraduate degree the same year she competed at the Barcelona Paralympics. By that point para sports in Canada were transitioning to a better high-performance model, but still not where they needed to be. But at least the travel and other costs for athletes on the Canadian Paralympic team were all covered this time like the Canadian Olympic team. Four years earlier, Carla recalled that her parents had to pay for her Canadian uniform and her flight to South Korea to compete at the Games. Langley actually held a big fundraiser to pay for Carla’s training and travel to go. They ended up raising enough money that Carla’s mom was also able to accompany her. By 1992, the Canadian Paralympic team was funded enough to cover these costs like the Olympic team. It was just one of many small improvements Carla witnessed during her competitive career.

“So many changes: integration and inclusion and equity,” she said. “All these big principles. All these things I spend my day thinking about today. All these little seeds were planted before.”

“So many changes: integration and inclusion and equity,” she said. “All these big principles. All these things I spend my day thinking about today. All these little seeds were planted before.”

At the Games Carla helped Canada to two more bronze medals in the 4x100m freestyle and medley relays. She was poised to take home her first individual Paralympic medal too, but disaster struck in the final of the 100m breaststroke when she finished a heartbreaking fourth, just three hundredths of a second from a bronze.

“My goggles fell off when I dove in,” she recalled “It was an outdoor pool and I’m almost totally blind in the sun, in which I can’t see anything basically, and I just had to keep swimming. You’re in the middle of it, you can’t fix your goggles. All the training and everything and my goggles fell off. It just happened. You wonder, if they hadn’t, could I have gotten third? But I’m proud of how I swam.”

Carla chose to retire from international competition after the Barcelona Paralympics.

“I was ready to be done with swimming after Barcelona. It wasn’t a long goodbye I guess you could say. I swam better times and I swam hard, but I was ready to move on to whatever was next.”

What was next was starting her law degree in 1993 in Ontario. While there she played goalball for Ontario after playing on Team BC for years. She helped Ontario to the 1993 national championship before demands on her time forced her to retire from competitive sport completely.

“That was my last hurrah in sport,” she said proudly.

Looking back on her competitive career, Carla believes her involvement in the Paralympics sparked in her the idea that mainstream sport needed to be more inclusive. The Paralympics were great, don’t get her wrong, but they were still separate.

Looking back on her competitive career, Carla believes her involvement in the Paralympics sparked in her the idea that mainstream sport needed to be more inclusive. The Paralympics were great, don’t get her wrong, but they were still separate.

“So how do we get Paralympic athletes the same recognition and opportunities as Olympic athletes? And how do we get more leaders that look like me? That really sparked my post-competitive sport career I would say.”

There were moments when Carla felt absolutely equal. Just before the 1988 Seoul Paralympics, the Canadian Paralympic swim team went to train with the Canadian Olympic swim team in Calgary.

“I got to swim with Mark Tewksbury. We trained together. I don’t know at that point that Mark knew who I was, but I certainly knew who he was. He was in the next lane to me and it was just this awesome moment of equality.”

Another moment came in 1992 after the Barcelona Paralympics. All of Canada’s Olympic and Paralympic athletes went to Ottawa to be recognized on the floor of the House of Commons, possibly the first time Canadian Olympic and Paralympic athletes were equally recognized in this way.

“They lined us up by medal, so I got to stand beside Silken Laumann because we both had bronze medals. And I’m like, ‘I’m standing with Silken Laumann!’ A moment of equal recognition—it was pretty powerful.”

So how do you go from these brief moments to changing the system so they are the norm all the time? That’s what began to drive Carla as she took her first steps transitioning to post-athletic life.

“I guess I really wanted to give back. Like I feel like sport saved me—and I’m not exaggerating, I really believe that. I wanted to give back to the system that had given so much to me and had taken me out of Langley and exposed me to the big world of opportunity. I was very deliberate. I knew if I wanted to be a leader, I had to get skills and I had to volunteer. So I just made choices that led me there.”

“I guess I really wanted to give back. Like I feel like sport saved me—and I’m not exaggerating, I really believe that. I wanted to give back to the system that had given so much to me and had taken me out of Langley and exposed me to the big world of opportunity. I was very deliberate. I knew if I wanted to be a leader, I had to get skills and I had to volunteer. So I just made choices that led me there.”

She began volunteering for organizations like Athletes CAN and the Canadian Paralympic Committee.

“I would do whatever anybody asked of me. If someone wanted me to go haul athlete luggage for a weekend, that’s what I would do. And if somebody needed someone to work drafting bylaws in a back room, that’s what I would do. Whatever got me connected to an event or an organization, whatever they needed, whatever I could learn from, that’s what I would do.”

Law school taught her about governance and human rights. She then leaned into that in relation to sport policy, athlete’s rights, and disability inclusion. It got her involved with work groups and advisory committees for the government of Canada. Combining both her sport involvement and burgeoning law career, she attended the 1996 Atlanta Paralympics as one of the first athlete advocates for any Paralympic team. There Carla was involved in a groundbreaking case where one of Canada’s athletes had been classified out of competition, but she led the appeal that returned the athlete to competition and he ultimately won a medal.

Carla quickly became more and more involved in the Paralympic movement and would attend nearly every Games thereafter. While volunteering in various roles and always looking for a way to make some headway moving the rights and experience of para sport athletes forward, she learned from powerful figures in the Canadian sport system like Marion Lay, Michael Chambers, Ann Peel, and Mark Tewksbury each of whom she considers a mentor.

“Wherever people needed help and I could be a part of something bigger, I was there. I was your gal. For me, it was about strategically poking the system and forcing the Olympic movement to see these other high-performance athletes in the system and maybe we should figure out how to be more inclusive and recognize the excellence of high-performance Para athletes. So I was really purposeful in the things I chose to do. By being at these tables and being a Paralympic representative, a lot changed in the Canadian sport system and I’m really proud of that.”

Over time she learned she was most effective at working within systems.

Over time she learned she was most effective at working within systems.

“There are activists who pave the way and bang on doors and hold the placards. And then there are advocates who sit at the tables and I’m one of the people who effects change best from the inside.”

She quickly built one of the most impressive resumes in Canadian sport. She served in various roles on the boards of Athletes CAN, Canadian Paralympic Committee (including president from 2006-10), Canadian Blind Sports Association, Canadian Olympic Committee, Commonwealth Games Canada, International Paralympic Committee, Sport Canada, Swimming Canada, Americas Paralympic Committee (vice-president from 2013-15), 2010 Legacies Now, Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, and the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (chair from 2010-13). She also played a key role in helping Toronto’s bid win the right to host the 2015 Pan and Parapan American Games and later helped with the Games organization. And then there was still her job as a lawyer, including working for the BC Human Rights Commission.

When asked if Carla ever slept given how long and varied her resume is, she laughed.

“Apparently not! It was good times. I have such fond memories. Getting ready for this conversation with you here reminded me how much joy I got out of doing it.”

So much joy in fact that when she did allow herself some time off from her day job she used to schedule her vacations around international sport events so she could volunteer at them.

All of her experiences left her well-prepared for the build-up to the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics and Paralympics. When IOC president Jacques Rogge announced Vancouver as the 2010 host in July 2003, she was in GM Place at the sold-out announcement event working for the sport minister, then in ensuing years with 2010 Legacies Now, and by the time the Games arrived she was serving as president of the Canadian Paralympic Committee.

All of her experiences left her well-prepared for the build-up to the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics and Paralympics. When IOC president Jacques Rogge announced Vancouver as the 2010 host in July 2003, she was in GM Place at the sold-out announcement event working for the sport minister, then in ensuing years with 2010 Legacies Now, and by the time the Games arrived she was serving as president of the Canadian Paralympic Committee.

“At that point I thought it was the culmination of everything I’d done in my life.”

In the years leading up to Vancouver 2010, every step of the way she fought as a matter of principle to ensure the Paralympics were treated equitably.

“If I was going to sit on this board and if the CPC was going to be a full-fledged partner, we were going to be treated fairly. We negotiated a lot of little game-changing moments in how the Games were integrated, how disability was perceived, and how para sport was treated.”

Two examples of little victories she remains proud of include the fact VANOC was the first Olympic Games organizing committee to include both Olympic and Paralympic in its name and the fact they ensured that the Royal Canadian Mint produced Paralympic medals that were comparable in size and value to their Olympic counterparts.

“These things have become common practice, but they were first in Vancouver.”

Her proudest accomplishment to date remains welcoming the world to her hometown in 2010.

“That was pretty much as good as it gets. Just being in the box in BC Place and watching Team Canada come in. I was pretty proud of that moment.”

“That was pretty much as good as it gets. Just being in the box in BC Place and watching Team Canada come in. I was pretty proud of that moment.”

One of Carla’s other strong memories of Vancouver was that she remembers attending countless events while about six months pregnant with daughter Jessica who was born a few months after the Games. Carla and husband Eron Main also have a son, Matthew, together and their blended family includes two children from Eron’s first marriage. Main himself was also an impactful international figure in sport having served as chief executive and secretary-general of the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation as well as other key roles in over 25 years involved in the sport. When it was pointed out to Carla that she and Eron make up one of the true power couples in BC sport, she laughed at the term, but there is no denying it is true.

“It was quite lucky because we both have the same perspective on what mattered and what we were willing to do as a family to participate and contribute to the Paralympic movement. We arranged our travel and family vacations around it.”

And it worked. In 2008 at the Beijing Paralympics, Erron was the technical delegate at the Games and Carla was there as the president of the CPC.

“So we took the kids and went to China for a month and volunteered,” she chuckled. They did the same at London 2012. He was a technical delegate again; Carla was with the International Paralympic Committee by then. Again, the kids came along—more of them actually this time.

“I don’t know, it’s crazy when I think about it, but doing something crazy never actually stopped us.”

Perhaps Carla’s riskiest move was still to come, stepping into a wholly new field outside sport: politics. She decided to run for election as Delta’s Member of Parliament. Taking many of the lessons she learned in sport and applying them to politics, she didn’t cut corners and simply put in the work. Acknowledging she didn’t know as much as she needed in this new field at first, she surrounded herself with people who knew politics and then she heeded their advice. If they said she needed to knock on 300 doors today, she did that. If she was directed to speak to this group here or give a speech there, she did that. Ultimately, Carla was elected as the first Liberal MP in Delta in 45 years in 2015. It also made her the first Paralympian ever elected to Canada’s Parliament and the first to serve as Canada’s Sport Minister, when new Prime Minister Justin Trudeau immediately named her to his cabinet.

Maybe the hardest part was an unexpected sacrifice Carla was forced to make once elected: she had to leave all volunteer sport positions, giving up participating in organizations that she truly loved.

Maybe the hardest part was an unexpected sacrifice Carla was forced to make once elected: she had to leave all volunteer sport positions, giving up participating in organizations that she truly loved.

“It was my life. It was the hardest thing of all the things. I miss it terribly because it was my world. It was my friendships and my relationships. It was how I spent my vacations. My husband and I met at a Paralympic event in Seoul, South Korea where he was involved with wheelchair rugby. It was our social circle. I will definitely be back. I’ve got a list of things I want to do next in sport now that I know what I know. Whenever this journey ends, I will veer back into sport.”

She took some solace in the fact she was now in a position as Minister of Sport and Disability to effect real change, although nothing would be easy.

“The prime minister said these are the two things you care the most about, so go out and change the world. That’s literally what he said to me. I said ‘Okay!’ And haven’t slept in eight years.”

She laughed out loud after that last line, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Juggling raising a family and her political commitments is a challenge at the best of times. When she was first elected, she and Eron had one kid in preschool, one in elementary school, one in high school, and one just starting university.

“That was a lot. But, again, we figured it out.”

But Carla also had a few things going in her favour in this new role. It helped that because of her sport background, she knew the sport system as well as anyone, which is often unusual for the Minister of Sport. They were able to get a lot of things accomplished because of that, like developing a national strategy for concussion protocol. And of course, in every decision she made she insisted that they treat Olympic and Paralympic athletes equitably.

But Carla also had a few things going in her favour in this new role. It helped that because of her sport background, she knew the sport system as well as anyone, which is often unusual for the Minister of Sport. They were able to get a lot of things accomplished because of that, like developing a national strategy for concussion protocol. And of course, in every decision she made she insisted that they treat Olympic and Paralympic athletes equitably.

“We really advanced the sport system around the para side.”

Carla served as Minister of Sport until 2017 before moving on to serve as Minister of Public Services and Procurement and Accessibility and later Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion.

But just because she had to leave many of her past volunteer sport positions behind didn’t mean she wasn’t still able to attend international events. She was at the 2016 Rio Olympics and Paralympics as Sport Minister and then also the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics (held in 2021) and the 2022 Invictus Games filling in as the government sport rep because the minister couldn’t go. Earlier this month she was in Santiago, Chile for the Pan American Games, after this summer’s cabinet shuffle shifted her back to Minister of Sport and Physical Activity.

When she looks back now at how para sport has evolved at a fundamental level from being excluded to included, she is optimistic at how many sports have integrated and real change has been made. But there is still more work to be done and more battles to be fought.

“I don’t think we’re at the point yet where a Paralympic medal equates to an Olympic medal. I think it does, but I don’t know what the Canadian people would say about that statement. It takes time. I’ve become more patient. In 2010 I would have told you I didn’t think we achieved all that I wanted to achieve around the equity piece of hosting the Games. Now looking back I’m pretty proud of what we achieved. When I was younger, I had less patience and less of a skillset of bringing people along with me. And now I know how hard it is to change systems and how these wins that we achieve if you do it right, they stick.”

“I don’t think we’re at the point yet where a Paralympic medal equates to an Olympic medal. I think it does, but I don’t know what the Canadian people would say about that statement. It takes time. I’ve become more patient. In 2010 I would have told you I didn’t think we achieved all that I wanted to achieve around the equity piece of hosting the Games. Now looking back I’m pretty proud of what we achieved. When I was younger, I had less patience and less of a skillset of bringing people along with me. And now I know how hard it is to change systems and how these wins that we achieve if you do it right, they stick.”

Through it all, even while sometimes working far from the sporting world, she maintains that sport remains the greatest shaper of her life.

“I feel like everything in sport prepared me for the next thing, whatever that was: being in Cabinet, being Sport Minister, even confronting non-sport systems as Minister for Disability and Inclusion. It’s the same skills, the same issues, the same barriers, but I learned all that through sport. I learned to self-accommodate. I learned that I had a right to be included. I learned about governance and decision making. About leadership. All those things I learned in sport. Now I’m using them elsewhere. For now.”

She laughed at that. If we’ve learned anything over the course of this article, it’s that Carla will inevitably find her way back to sport or sport back to her. It’s always been at the heart of who she is, what she’s done, and where she’s going.

“I don’t think I could give back to sport what sport has given to me. Whether it’s friendships or confidence or even like the system of sport. When I got involved in the Paralympic movement, it sparked in me this idea that we could build systems that were inclusive from the beginning that included people like me with disabilities. I got to travel around the world and see how disability was treated in other countries. How in some countries people with disabilities were hidden. There was a lot of discrimination out there. And then you see the system where everyone is included. The idea that this sport system could change attitudes around

disability and what people with disabilities can and cannot do. I totally fell in love with that kind of idea. And what if we did this in other systems? What if we made transportation or education or anything more inclusive from the beginning? That seed was planted. My human rights career, what I’m doing now [as an MP], it all was planted in this whole exposure during sport, these big ideas of accommodation yeah, but then this idea of inclusion, and it all mushroomed for me. It’s super powerful.”

Powerful enough that it has literally improved the lives of countless Canadians along the way and is what continues to drive her forward.

Already inducted into the Canadian Paralympic Hall of Fame (2017) and the Canadian Disability Hall of Fame (2021) and recognized among Canada’s most influential women in sport on several occasions, her induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame was still an overwhelming reward for a lifetime devoted to sport.

“Oh my goodness. First of all, to get the scarf—a bunch of my friends have the scarf—it’s an honour. I’ve been very lucky to have been recognized in a whole bunch of ways for what I have achieved but being recognized by your peers and having just a place where people will think about what you did is pretty special. The people in the BC Sports Hall of Fame are people I admire and people I adore and people who have made a real difference in sport in Canada. BC’s on the cutting edge of sport leadership and to be in that group of people is a big honour.”

As part of the Class of 2023, Carla Qualtrough was formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Builder-Coach category at the annual Induction Gala held June 1, 2023 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.