Walter d’Hondt: Engine of the Engine Room – A Tribute

January 31, 2022By Jason Beck

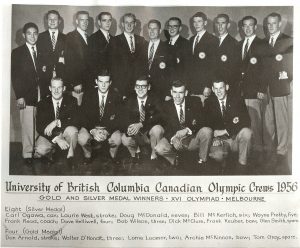

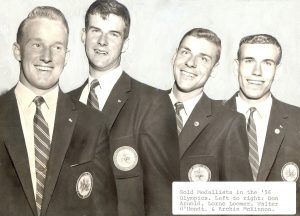

In November 2017, Don and Linda Arnold organized an interview for me with the great Walter d’Hondt. Don and Walter were teammates on the 1956 UBC-Vancouver Rowing Club Fours rowing crew that won gold at the Melbourne Olympics and also on the 1960 UBC-VRC Eights crew that won silver at the Rome Olympics. The interview with Walter was fantastic and many of the quotes attributed to him in the tribute that follows below are from that sit-down together.

But maybe the most illuminating moment of the meeting came at the very beginning. Before the interview started, Don and Linda pulled out a wrapped present for Walter, who was genuinely surprised.

“Oh my goodness,” Walter exclaimed for the first of half of dozen times, one of several gentle phrases I learned later that many associated with him despite his reputation as one of the strongest oarsmen they’d ever seen.

“Open it up and see. You might remember,” chuckled Don.

Walter unwrapped the present and his eyes lit up. He found inside an old English Rolls shaving razor sharpening kit that had belonged to his father. Walter had given it to Don back in October 1956 as they were packing up their gear at the Vancouver Rowing Club in preparation for the long flight to the Melbourne Olympics, where they would ultimately become Olympic champions. Walter didn’t have any extra space in his bag for the sharpening kit, so he asked Don to hold onto it for him. Don put it with his stuff being moved to a house near UBC where he was living then. And then life happened and the kit was initially forgotten.

When the kit resurfaced Don kept it in the hope that he’d return it to his friend one day. He packed it with him on cross-continent moves to California, Indiana, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and back to BC. He and Walter kept in regular contact over many decades, but Don always forgot to bring the kit when they met in person.

When the kit resurfaced Don kept it in the hope that he’d return it to his friend one day. He packed it with him on cross-continent moves to California, Indiana, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and back to BC. He and Walter kept in regular contact over many decades, but Don always forgot to bring the kit when they met in person.

It went on like that until this day, 61 years later, when Walter was reunited with his father’s razor sharpening kit. More significantly, a promise made many years ago between teammates was finally fulfilled. It’s just another example I’ve seen over the past 15 years that the bonds of old rowers run deep and strong.

Countless hours and miles and races in rowing shells on waterways both close to home and halfway around the world chasing Olympic medals and dreams will do that. Being young and learning how to live life side-by-side in university classes, as roommates, on work crews, and in sleek rowing shells forged a bond that stretched decades. Long after the last stroke to the finish line, they remained brothers of the oar.

So when one of the band of brothers departs, it’s a loss that is felt deeply among all. Earlier this month a group email circulated with news that the revered Walter d’Hondt had passed away in mid-December at the age of 85. Right away short tributes and recollections began firing back and forth by email among old teammates. It soon became clear Walter was not only one of the most powerful oarsmen of those groundbreaking crews coached by the legendary Frank Read in the 1950s and 1960s, but also one of the most universally popular and respected. Here’s a sampling:

“Walter was the Power Seat in our ’56 Four. Where did we get such a rower as Walter? I cannot remember Walter ever riding the coach boat! You don’t ‘pull’ a 6’4” 200 lb oarsman, who came to row every day. The rest is history. Thanks Walter, it was terrific rowing with you and being part of a ‘magic’ crew. You will be missed!” –Archie MacKinnon, UBC-VRC teammate, 1955-60

“I’m so sorry to hear the news. Walter will be sorely missed by us all. No coach boat rider indeed! ‘Heavens, why would one ever venture into such a contraption?’… In training for the 1958 Commonwealth Games we all lived in cramped quarters beneath Varsity Stadium, rising at some ungodly hour to be on the water by 6am. One morning as we barreled down 4th Avenue a cop appeared at Alma and flagged us down. Walter cried out ‘Heavens! A speeding ticket.’ He frequently used that polite word.” – Gordon Green, UBC-VRC teammate, 1958-60

“I think that the point that should be illustrated is whereas nine out of ten guys would have used an expletive that was not the case with Walter. Never, to my recollection, did he use one… Stand tall, stand strong, and stand proud. Walter would wish it.” – Laurie West, UBC-VRC teammate, 1955-56

“When my husband Don Arnold talked with me about the various races in which he stroked the boat, it was almost always Walter sitting right behind him. He said Walter would usually start talking softly to himself as the race was underway, saying ‘… more power, more power…’ and sure enough, the power was there. I feel so privileged to have known Walter, a gentle person with a wonderful sense of humour, smart, humble, and a fierce competitor. Like all the men in the gold medal four, Walter never gave up.” – Linda Arnold, long-time friend, wife of the late Don Arnold, UBC-VRC teammate, 1955-60

“Belated thanks to Wayne [Pretty] who was key to finding jobs on the gas pipeline being installed from Kamloops into the Okanagan Valley in the summer of 1955 for Bill [McKerlich], Walter and myself. I have enjoyed a long friendship with Walter and Bill as a result. I last spoke with Walter before Christmas when we spoke of getting together once the COVID crisis died down. Walter’s departure will sadden a lot of us. We will never know, but I think it a good bet that Walter was the strongest oarsman in the world when at his peak.” – John Madden, UBC-VRC teammate, 1955-59

“On the pipeline Walter`s job was to put a heavy cast-iron cap on the end of each joint of pipe so the pipe could be bent to fit the contour of the land. The tractor driver was supposed to winch the cap into position so Walter could fit it to the end of the pipe. Walter often did not wait for the driver to do the winching. He was so strong he would just lift the cap and put it into place…. Walter was a powerful fellow crew member and a thoughtful friend. We will miss him.” – Bill McKerlich, UBC-VRC teammate, 1955-60

“Thanks everyone for the update re: The Golden Four. Walter’s passing is a shock to me and I suspect others. They were exceptional people: Don, Lorne [Loomer], and now Walter! I have always been proud to have known them. I cannot give Walter the praise he needs. I am wordless re: this subject. He was a great man.” – Glen Smith, UBC-VRC teammate, 1955-58

“My god, he was excellent. A fantastic teammate. A great sense of humour.” – Art Wright, Ancient Mariners Rowing Club (Seattle) teammate for twenty years

“I would like to join the rest of you in paying tribute to Walter, the gentle giant. My earliest memory of Walter was the summer of 1959, the evening prior to the team’s departure to Chicago [for the 1959 Pan American Games]. Walter decided the crew/frat house needed cleaning, so he inverted me and proceeded to sweep the floor, (blame Bud Stapleton’s homemade saké). I also spent a great summer with him in 1961 on the pipeline in Pincher Creek, again courtesy of Wayne getting Walter, Don, “Gunny” Finch, and myself jobs out there. After that I occasionally phoned or met up with him in Seattle whenever I was there, and of course there were always the UBC-VRC reunions. Yes, he will be fondly remembered as are Don and Lorne [Loomer].” – Bob Stubbs, UBC-VRC teammate, 1959-60

Like his ’56 ‘Golden Four’ teammates, Walter d’Hondt stands as a pillar of Canadian rowing. He remains one of the most decorated Canadian rowers in history. Beyond being the engine of the ‘Engine Room’ in the ’56 Four that won Canada’s first-ever Olympic gold medal in rowing, Walter also won two medals at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games (gold in the eight and silver in the coxed four), a silver in the eight at the 1959 Pan American Games (as a late addition), and of course another silver in the eight at the 1960 Olympics. But if any of the above messages from his teammates have shown us anything, international medals were just a part of who Walter was.

Like his ’56 ‘Golden Four’ teammates, Walter d’Hondt stands as a pillar of Canadian rowing. He remains one of the most decorated Canadian rowers in history. Beyond being the engine of the ‘Engine Room’ in the ’56 Four that won Canada’s first-ever Olympic gold medal in rowing, Walter also won two medals at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games (gold in the eight and silver in the coxed four), a silver in the eight at the 1959 Pan American Games (as a late addition), and of course another silver in the eight at the 1960 Olympics. But if any of the above messages from his teammates have shown us anything, international medals were just a part of who Walter was.

Ignace Xavier d’Hondt was born September 11, 1936 in the small town of Richmond about eight miles west of London. His given name was an admitted mouthful so the d’Hondt’s eldest child took the name ‘Walter’ after his father. Walter would later be joined by three younger sisters, who nicknamed him ‘Pickle.’ Early on the d’Hondt family lived in a house above the Thames River in Richmond. Living so close to London during the Blitz of World War II could be a daily question of life and death and many families moved to the country to be out of harm’s way. The d’Hondt’s stayed put and came out unscathed—barely.

“At the end of the war in ’44, maybe the beginning of ’45, when they had the buzz bombs come over, our house got blasted by a near direct hit,” recalled Walter. “All the ceilings and the windows and everything, it was unlivable.”

The d’Hondt’s moved to the countryside and rode out the rest of the war, but made the decision that it was time to find a more stable place to raise their family. In 1948 they moved to Vancouver. Work for Walter’s father was difficult to find at that time with the influx of returning soldiers from the war. He took a job up in Woodfibre near Squamish and somehow commuted there daily from their home in Point Grey, not an easy journey in those days.

From there the family moved around frequently as Walter Sr. chased work: off to Montreal next, then back to England, and back to Montreal. It was difficult for a young boy in his teens to put down roots.

From there the family moved around frequently as Walter Sr. chased work: off to Montreal next, then back to England, and back to Montreal. It was difficult for a young boy in his teens to put down roots.

“The only consistency that I could sort of hang anything on was something to do with sports, so that’s how I got into it,” Walter recalled.

While attending St. George’s School in Vancouver for instance, Walter became one of the school’s top cross country runners. But it was during the family’s return to England that Walter had his first true breakthrough in sport. While attending The John Fisher School, a Catholic school in the county of Surrey near London, Walter joined the track and field team, which had won the All-England schools championship the previous year. The priest who ran the school’s athletic program decided to bring in a coach who was making a name for himself throughout Britain. The coach’s name was Franz Stampfl, who in just a few short months would coach Sir Roger Bannister to history’s first sub-four-minute mile in May 1954. Stampfl came down to Walter’s school to coach the track team a couple of days a week. From Stampfl Walter learned proper technique for throwing the discus and hammer.

“I was 15 or 16 when I went into my first discus competition,” he said. “I remember it very well because the umpires were all standing out there with their sticks to put the marks in. Well, I threw it over their heads.[laughs] And set a new Surrey record. So that was a sort of an intro. But it was all technique. It wasn’t any special, I don’t think, any special strength. He taught the technique.”

Stampfl was undoubtedly one of the great track and field coaches of his time, but Walter as usual is being incredibly modest here. Stampfl had an incredibly gifted and bright athlete to work with in Walter. He went on to finish third in the hammer in all of England as The John Fisher School won the All-England championship for a second year in a row.

“Stampfl was an excellent coach,” remembered Walter, “but he was also an excellent thinker and philosopher. He connected with the individual, to the person’s life and endeavours and basically the person’s spirit you might say.”

Although his time working under Stampfl was brief, there were lessons he learned that stayed with Walter, particularly when he later picked up an oar. In fact, Walter must stand as the only athlete of his time lucky enough to be coached by two of the greatest coaches ever in their respective sports back-to-back. Stampfl remains a legend in the track world and Walter was about to learn to work under the great Frank Read.

When the family moved back to Montreal, Walter continued training in the discus and hammer under the guidance of a Hungarian tailor who had also escaped to Canada. Walter progressed in the hammer to that point so rapidly that in 1954 he was likely the best hammer thrower in the country. The problem was the Canadian trials for the British Empire and Commonwealth Games were to be held in the west. Walter didn’t have the money to travel to them and so missed out on competing at his first international games. Had he gone, perhaps his story never enters the rowing realm.

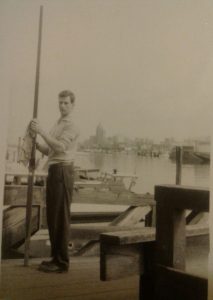

In the Fall of 1955, Walter moved back to Vancouver to attend UBC working towards a degree in math-physics. He was still training for the hammer, but wasn’t getting much out of it until one of his future Olympic gold medal teammates entered the picture.

“It was a lonely experience,” he remembered. “I was out there by myself on the field with very limited coaching and it wasn’t very social. However, I think it was probably near the middle of October that I was in the showers with Lorne Loomer, who was kind of the instigator. We started talking and he said, ‘Well, why don’t you turn out for the rowing workouts?”

“It was a lonely experience,” he remembered. “I was out there by myself on the field with very limited coaching and it wasn’t very social. However, I think it was probably near the middle of October that I was in the showers with Lorne Loomer, who was kind of the instigator. We started talking and he said, ‘Well, why don’t you turn out for the rowing workouts?”

Ah yes. Walter was just another in a long chain of UBC rowers initially snagged hook, line, and sinker into coming out for a fun little calisthenics workout at the gym. It’ll be great to get some exercise and maybe meet a few new people, he thought. As most unsuspecting rookies were to discover, the brutal MacDonald’s abdominal exercises were anything but fun.

“When a few friends heard that I was turning out for that, they said, ‘Oh, people don’t survive that!’” Walter chuckled.

As his future UBC-VRC rowing teammates would soon find out, Walter d’Hondt was built differently than the average human. He not only survived the weeks of grueling MacDonald’s ‘abominable’ exercises, he thrived under them. That same fall, he held an oar for the first time in one of the training barges out on the water. Although he essentially grew up on the Thames, the historic home of the Henley Royal Regatta and the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race among many other regattas and rowing activity, ironically Walter had never rowed before except for once with his mother in a seated boat while still in England. Needless to say, with his prodigious physical size and strength, as well as the athletic engine of a runner and his willingness to put in the necessary hard work, he took to rowing like a duck to water.

“I think the whole rowing experience for me was a natural,” he said. “The ability to put leverage on the oar with the legs and the upper body, was a very natural thing for me. I liked the rowing motion and then particularly the breathing where you could breathe at a reasonable rate to put out a certain amount of energy.”

The other aspect that immediately appealed to Walter was the camaraderie of rowing.

“This is something that is difficult to explain, but medals are definitely taken as a measure of success, but the nature of a crew and the integration of the people on the crew, the camaraderie, is by far a measure that I would harken anybody to experience,” he said in 2017. “All my teammates, we see each other from time to time now some sixty years later and it’s still an experience to shake their hands. There’s some chemistry that comes across when you shake somebody’s hand that they realize that you’ve gone through something and this was an experience. So I wouldn’t say I want to throw medals away or anything, but even if we’d never won, the experience would still have been an amazing thing. Because there’s no question that whatever we achieved in rowing was all done in the practice and the camaraderie.”

And not long after Walter was introduced to his new coach Frank Read.

“I could tell when I met Frank that his personality was all that you needed,” he recalled as he delved into a comparison between his two great coaches Stampfl and Read. “Franz and Frank were both individuals who were mentally strong in their own right and they were confident in what they could do themselves. The difference being Stampfl relied on some kind of psychological strength of his own personality to carry the athlete to the finish line, in contrast to Frank’s ability to drive individuals as hard as he drove us as a crew. So Frank had an ability to drive people and I liked that.”

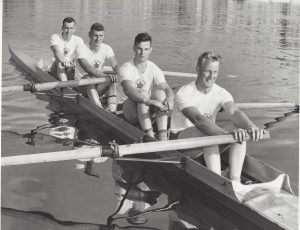

By the early spring of 1956, Read had his Varsity eight crew pretty much set and he focused his attention on them, but a new four had emerged—Walter, Archie MacKinnon, Lorne Loomer, Bill Hughes initially and then ultimately Don Arnold—that was also vying for any scrap of his coaching they could get. In training rows on Coal Harbour, this determined four worked devilishly hard to keep up with the eight and be in earshot to receive a few precious gems of Read’s instruction. Read typically paid little mind to any trailing boats, but this four he had to admit was different.

By the early spring of 1956, Read had his Varsity eight crew pretty much set and he focused his attention on them, but a new four had emerged—Walter, Archie MacKinnon, Lorne Loomer, Bill Hughes initially and then ultimately Don Arnold—that was also vying for any scrap of his coaching they could get. In training rows on Coal Harbour, this determined four worked devilishly hard to keep up with the eight and be in earshot to receive a few precious gems of Read’s instruction. Read typically paid little mind to any trailing boats, but this four he had to admit was different.

“They didn’t look like much, but they sure could move the boat,” he once said.

Part of the reason was the power and strength of Walter in the number three seat was just undeniable. Teammates remembered how massive his hands were compared to their own and how he could lift the end of a car off the ground by himself. One day in particular out on the water illustrated just how strong he truly was. Don Arnold related this amazing story back in 2017:

“That morning we weren’t doing all that well. We weren’t going as fast as we should go. Our boat was plowing water rather than skimming on the surface and Frank decided to give us some coaching. And he basically gave us one or two words…I was going to say bad words, but I’ll just say words. And one of which was ‘Break that goddamned oar will ya?! Where is your strength?!’ I can recall right to this minute that I heard this sort of hmmpff, grunt behind me from Walter. And he drove his legs down and he had a hold of that oar and he just went ccccraaaaacck! Read yelled, ‘Stop that boat!’ And Walter stopped rowing and just kind of sat there. Walter had snapped his 12-ft Pocock oar right by the button—and that’s a laminated oar, so there’s a lot of power behind that. That was the only time that I ever saw an oar break like that.”

Everyone on the water that day paused in some measure of shock and awe. The story of Walter’s broken oar became legendary over the years. It wasn’t long after that his teammates began calling Walter by his new nickname ‘Ace.’

Sitting directly in front of him in shells for nearly five years, Arnold tagged Walter with another nickname as well: ‘Mumbles.’ It was for the way he spoke to himself under his breath as they rowed.

“Walter was a self-motivator,” said Arnold. “He talked to himself in very positive terms. I could hear him behind me. ‘More power.’ ‘Stronger.’ ‘Timing.’ ‘Big Ten.’ ‘More Power.’ ‘Focus.’ For 2000m, he was telling himself what he had to do right behind me. Nobody else could hear him. And it wasn’t loud. It was very subdued, but I could hear what he was saying, so the two of us worked in many ways like a team.”

Like everyone, Walter also had his unique quirks. As many of his teammates can attest, driving was not one of his strengths and many a curb in Vancouver and his later home in Seattle was bumped over as Walter drove with one hand on the wheel while holding a coffee in the other hand. And somewhat ironically for a rower, swimming was not one of his strengths either. One day during a training session, the crew learned the most natural of athletes among them remarkably couldn’t swim. On a particular stroke Walter was fighting his oar, caught a crab, and was pitched into the air out of the shell and splashed into the water.

Like everyone, Walter also had his unique quirks. As many of his teammates can attest, driving was not one of his strengths and many a curb in Vancouver and his later home in Seattle was bumped over as Walter drove with one hand on the wheel while holding a coffee in the other hand. And somewhat ironically for a rower, swimming was not one of his strengths either. One day during a training session, the crew learned the most natural of athletes among them remarkably couldn’t swim. On a particular stroke Walter was fighting his oar, caught a crab, and was pitched into the air out of the shell and splashed into the water.

“We stopped the shell and waited, but for quite a while no one surfaced. Out of the depths came Walter sputtering and splashing in a dog paddle stroke,” Arnold recalled later as they pulled their sinking teammate out of the water and back into the boat.

The ’56 Four of course went on to shock the Canadian rowing community with a dominant record breaking performance at the Canadian Olympic trials. From there, they and their UBC-VRC teammates in the Eight flew to Melbourne and took gold and silver respectively at the Olympics. Walter didn’t know it at the time, but also down in Melbourne was his old coach, Franz Stampfl. After the rowing events were over, they ran into one another in the Athlete’s Village. A delightful moment ensued for both as Franz had not yet heard of the gold medal result and asked how they had fared.

“I distinctly remember Walter’s response,” recalled teammate Laurie West recently. “’We won.’” Stampfl, no doubt, must have been as immensely proud of him as Read was.

Although Walter went on to win other international medals with the UBC-VRC crews, he always viewed the ’56 Four as the high watermark of his rowing career. He retired from rowing after the 1960 Olympics. As a key member of some of the greatest rowing crews ever produced in Canada, he would be inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame, the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame, the UBC Sports Hall of Fame, and the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Along the way he raised a family in the Seattle area, while working for Boeing for fifty years. In his late fifties, Walter returned to rowing as a member of the Ancient Mariners Rowing Club in Seattle, for whom he rowed for over two decades.

To bring this tribute to a great rower, teammate, and friend to a close, there was one other anecdote that Walter shared during our interview that stuck with me and seems sadly fitting now. He talked about how when his family were still living in England during the war he’d often look up and see the ravaged fighter planes and bombers returning from their missions in France and Germany.

“You could see how damaged they were,” he said. “They flew in formation but when they came back, you could see that they were missing planes. You’d hear this pup-pup-pup pup-pup-pup of engines cutting in and cutting out and some of these planes were coming back on two engines instead of four. The rear of some of the planes were shot away and some of the airmen were killed and dead in the planes. These are young kids, 18-20-year-olds, in those planes. There’s a lot of courage here, that goes into this. You’ve got to put out and do things and you’re put in tough situations…maybe they can make it home and they succeed in doing it. But those are the kind of images that I brought into rowing that I really felt.”

“You could see how damaged they were,” he said. “They flew in formation but when they came back, you could see that they were missing planes. You’d hear this pup-pup-pup pup-pup-pup of engines cutting in and cutting out and some of these planes were coming back on two engines instead of four. The rear of some of the planes were shot away and some of the airmen were killed and dead in the planes. These are young kids, 18-20-year-olds, in those planes. There’s a lot of courage here, that goes into this. You’ve got to put out and do things and you’re put in tough situations…maybe they can make it home and they succeed in doing it. But those are the kind of images that I brought into rowing that I really felt.”

His UBC-VRC and Ancient Mariners teammates know that Walter gave everything for his crew whenever out on the water in a rowing shell.

The seat in the engine room occupied by the great Walter ‘Ace’ d’Hondt may now be empty, but his teammates continue to row on in formation in his memory.