Shared PNE Roots: The Challenger Map and the BC Sports Hall of Fame

December 29, 2021By Jason Beck

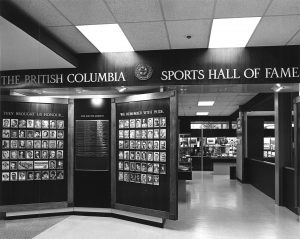

It’s a little ironic given my place of work for the past 18 years, but I have to admit I do not have any memories of the original BC Sports Hall of Fame located in the BC Building (later called the BC Pavilion) at the PNE from 1966 to 1992.

My dad, Dennis Beck, has plenty of memories of the original Hall visiting it each summer in his teens on extended 4-H Club stays at the PNE Fair. I wish I could say that I remember the Hall’s original displays, stood in awe of the lifelike Cyclone Taylor, Willie Fleming, or Lester Patrick wax figures or happened to meet Eric Whitehead or Peter Webster, two of the key individuals in the Hall’s first two decades of existence. But I’ll have to take my mom and dad’s word for it that we visited the Hall as a family during our annual summer trek into Vancouver for the Fair like so many other BC families did and still do.

My dad, Dennis Beck, has plenty of memories of the original Hall visiting it each summer in his teens on extended 4-H Club stays at the PNE Fair. I wish I could say that I remember the Hall’s original displays, stood in awe of the lifelike Cyclone Taylor, Willie Fleming, or Lester Patrick wax figures or happened to meet Eric Whitehead or Peter Webster, two of the key individuals in the Hall’s first two decades of existence. But I’ll have to take my mom and dad’s word for it that we visited the Hall as a family during our annual summer trek into Vancouver for the Fair like so many other BC families did and still do.

I do have one vivid memory from a visit to the BC Building though. I was maybe four or five years old and I can remember clutching a railing and peering over the edge to see what lay below. I was standing on my tiptoes on a moving steel bridge that spanned over one of the most remarkable sights I had ever seen to that point: the magnificent Challenger Map of BC, for many years the largest topographical relief map in the world.

Unveiled in June 1954 in the brand-new BC Building just in time for the British Empire and Commonwealth Games held just a stone’s throw away at Empire Stadium, millions of visitors gazed in awe at George P. Challenger’s wondrous creation over the next 43 years. Some called it ‘the Eighth Wonder of the World’ and few made any argument on that point. At 80 x 76 feet in size (6,080 sq ft) in 1992 the Guinness Book of Records named the Challenger Map the World’s Largest Relief Map.

Showing the entire province of BC, plus adjoining parts of Washington State, Idaho, Montana, Alaska, Alberta, and the Yukon, the map accurately depicted nearly 1.5 million square kilometers of land. Built to a horizontal scale of one inch equaling one mile and a vertical scale of one inch equaling 1000 feet, the map clearly displays just how rugged BC’s mountainous terrain truly is with countless peaks and canyons carved by powerful waterways. A ride on the moving bridge provided an overhead tour of the province in just three and a half minutes, the equivalent of a flight over the province at 27,300 km/hr.

Showing the entire province of BC, plus adjoining parts of Washington State, Idaho, Montana, Alaska, Alberta, and the Yukon, the map accurately depicted nearly 1.5 million square kilometers of land. Built to a horizontal scale of one inch equaling one mile and a vertical scale of one inch equaling 1000 feet, the map clearly displays just how rugged BC’s mountainous terrain truly is with countless peaks and canyons carved by powerful waterways. A ride on the moving bridge provided an overhead tour of the province in just three and a half minutes, the equivalent of a flight over the province at 27,300 km/hr.

Built out of 986,000 individually cut, painted, and assembled pieces of ¼-inch fir veneer cut from approximately 8000 4’x8’ sheets and mounted on 196 4’x8’ plywood sheets donated by H.R. MacMillan, the map is a remarkable feat of construction. It took George Challenger and his family approximately 20,000 hours over seven years, from 1945-52, to complete the map. And he built it in sections piece-by-piece using just a little Do-All jigsaw in his basement. Read that again. Incredibly, it had never been assembled in full until it was installed in the BC Building. It means it might also be one of the largest jigsaw puzzles ever constructed.

“Imagine building a province in your basement and taking it out piece by piece,” marveled former Social Credit cabinet minister Grace McCarthy to John Mackie of the Vancouver Sun in 2009.

Just the sheer amount of sawdust created by this project in the Challenger household must have been mindboggling.

“My poor mother,” said Challenger’s daughter Ruth Munn to The Province’s Tom Hawthorn in 1992. “You can imagine the sawdust, paraphernalia. He even cut a hole in the floor of the sunroom so he could set up his projector.”

And there’s more. Challenger utilized grainy RCAF and US Army aerial photos, old survey maps, and his own personal observations to create the map. He would go through 5000 yards of specially manufactured 48-inch tracing paper to sketch out each line and contour of the land he would shape in layers of wood. He spent $252,000 of his own money to build the map. He later sold it to the PNE for $50,000.

And there’s more. Challenger utilized grainy RCAF and US Army aerial photos, old survey maps, and his own personal observations to create the map. He would go through 5000 yards of specially manufactured 48-inch tracing paper to sketch out each line and contour of the land he would shape in layers of wood. He spent $252,000 of his own money to build the map. He later sold it to the PNE for $50,000.

“I built the map not for money but as a tribute to BC,” Challenger said in 1962.

Originally from Mitchell, Ontario, Challenger had first visited BC in 1896 when competing in a bicycle race and immediately fell in love with the province. He moved here permanently with his family in 1910. He worked as a prospector and timber surveyor all over BC and later became a millionaire through his mining and logging ventures back when the term actually meant something. Part of the reason for his success was his early use of rudimentary relief maps he began making out of plasticine in the 1920s to plot the most efficient railway routes to remove timber from remote parts of BC. During World War II he constructed a relief map of southwestern BC for military and evacuation purposes. Then came the Challenger Map. For seven years, he only took one day off—a Christmas—and often worked 18 hours a day in his basement on the task some told him was impossible to complete. When he started the project he was a rotund 290 lbs, but he had worked off 120 lbs by the time it was finished. Seven family members and up to 20 employees were assisting him at the project’s height.

The map was checked for accuracy by the BC Surveyor-General’s Department after. Over the years the map was used many times for planning and plotting out major projects around BC—pipelines, highways, railways, hydroelectric dams, and power line projects. Surveyors used the map to determine the best route for the Coquihalla Highway. Another time BC Hydro planners used the map to plot the best pathway for power lines from the WAC Bennett Dam in northern BC. Challenger liked to point out that his map proved the best route for the Alaska Highway was west and north from Hazelton, BC, not the route pushed through muskeg and along canyon walls at many extra millions of dollars during WWII.

The map was checked for accuracy by the BC Surveyor-General’s Department after. Over the years the map was used many times for planning and plotting out major projects around BC—pipelines, highways, railways, hydroelectric dams, and power line projects. Surveyors used the map to determine the best route for the Coquihalla Highway. Another time BC Hydro planners used the map to plot the best pathway for power lines from the WAC Bennett Dam in northern BC. Challenger liked to point out that his map proved the best route for the Alaska Highway was west and north from Hazelton, BC, not the route pushed through muskeg and along canyon walls at many extra millions of dollars during WWII.

Proud of his adopted province and the immense map he created of it, when George Challenger passed away in 1964 at the age of 84, an urn containing his ashes was placed underneath a plaque near the bottom of the map. It remained there until the map’s removal in 1997 when the aging BC Pavilion was demolished. Challenger’s ashes were kept with family, while his beloved map was taken apart and put in storage in an Air Canada hangar at Vancouver International Airport. In 2010 the southwestern portion of the map—just eight of the 196 total panels or 4% of the total map—was refurbished and brought out of storage for a display at the Richmond headquarters for the RCMP Integrated Security Unit for the Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. After another 11 years in storage, the Challenger family and the PNE signed an agreement to work towards finding a permanent home for the map back at the PNE. The refurbished southwestern portion of the map was brought back out on display at the PNE Fair and then for several months at Canada Place.

placed underneath a plaque near the bottom of the map. It remained there until the map’s removal in 1997 when the aging BC Pavilion was demolished. Challenger’s ashes were kept with family, while his beloved map was taken apart and put in storage in an Air Canada hangar at Vancouver International Airport. In 2010 the southwestern portion of the map—just eight of the 196 total panels or 4% of the total map—was refurbished and brought out of storage for a display at the Richmond headquarters for the RCMP Integrated Security Unit for the Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. After another 11 years in storage, the Challenger family and the PNE signed an agreement to work towards finding a permanent home for the map back at the PNE. The refurbished southwestern portion of the map was brought back out on display at the PNE Fair and then for several months at Canada Place.

And now for the first time in 30 years, the Challenger Map and the BC Sports Hall of Fame have been reunited. Once neighbours in the BC Building, they come together again this time in BC Place. The Hall of Fame and the Challenger Map were so closely connected for so long, decades after our move to BC Place countless visitors still ask us during their visits ‘whatever happened to the giant map?’

And now for the first time in 30 years, the Challenger Map and the BC Sports Hall of Fame have been reunited. Once neighbours in the BC Building, they come together again this time in BC Place. The Hall of Fame and the Challenger Map were so closely connected for so long, decades after our move to BC Place countless visitors still ask us during their visits ‘whatever happened to the giant map?’

Well, in 2022 we can tell you it’s just down that hallway and to the left. We also plan to display a little of the Hall of Fame’s shared roots in the PNE’s BC Building and perhaps even look at how BC’s unique terrain and climate have shaped sport here.

If you’d like to support the fundraising efforts to refurbish the rest of the Challenger Map and build it a permanent home, please visit us over the next six months and make a donation. You can find more information on the Challenger Map here: https://challengermap.ca/campaigns/friends-of-the-challenger-map/donate/