Pamela Rai, Warrior of the Water and Forest: Asian History Month Feature

May 28, 2021By Jason Beck

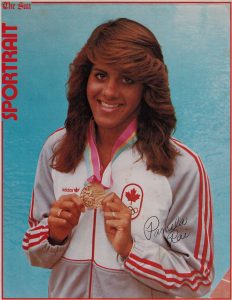

In terms of her larger life story, Pamela Rai might be one of the most interesting, well-rounded Honoured Members inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame. As a Canadian international swimmer in the 1980s who was the first woman of Indian ancestry to win an Olympic medal, I’ve long felt Pamela’s athletic story should be better known among British Columbians, so what better time than right now for Asian Heritage Month. But I never could have guessed how much more there is to her story beyond swimming.

As a Canadian international swimmer in the 1980s who was the first woman of Indian ancestry to win an Olympic medal, I’ve long felt Pamela’s athletic story should be better known among British Columbians, so what better time than right now for Asian Heritage Month. But I never could have guessed how much more there is to her story beyond swimming.

Pamela spoke to me by phone earlier this month from her Nanaimo property complete with backyard swimming pool she still enjoys. But that’s often not where you’ll find her these days. In fact, I can’t ever recall hearing an explanation for being hard to reach quite like what Pamela offered.

“If I don’t get back to you, it’s because I’m at a camp out in the bush at a blockade,” she said, pausing momentarily and then continuing with a chuckle. “Or I’m in jail.”

Although she laughs at this, she’s also quite serious. Pamela Rai has been many things during her life—child swimming prodigy, Canadian record holder and national champion, Olympic medalist, coach, high school teacher, artist, academic, social justice warrior, yoga instructor—but these days she’s an activist. You can often find Pamela out on the front lines  fighting for our old growth forests as part of the Rainforest Flying Squad, a volunteer non-violent movement committed to protecting the last stands of old growth left on Vancouver Island. Less than three percent of ancient temperate rain forest remains in BC and yet the provincial government continues to issue licenses to clear-cut these areas. It’s something Pamela is very passionate about and more than willing to sacrifice for, even if it means ending up in handcuffs.

fighting for our old growth forests as part of the Rainforest Flying Squad, a volunteer non-violent movement committed to protecting the last stands of old growth left on Vancouver Island. Less than three percent of ancient temperate rain forest remains in BC and yet the provincial government continues to issue licenses to clear-cut these areas. It’s something Pamela is very passionate about and more than willing to sacrifice for, even if it means ending up in handcuffs.

“I don’t care,” she said. “I’m fearless. They want to throw me in jail for saving old ancient trees? Go ahead. I feel standing up for what is right and just, alongside my Indigenous brothers and sisters, is in the spirit of the Olympic movement. All great athletes have a rebellious, non-conformist streak – a characteristic which when channeled in a good way, leads to a better world.”

Pamela creates the Rainforest Flying Squad’s logos, helps run the movement’s social media channels, and serves as one of the group’s police liaisons. She recently retired from a 27-year teaching career mostly with Nanaimo District Secondary and Ladysmith Secondary to dedicate her time to this cause.

“I’m heavily involved in blockading,” she said. “This is so reminiscent of my swim career and how much I’m putting into it—just the dedication and the fierceness and the ‘warrior-ness’ of it. The fearlessness I have in risk-taking and venturing out and having the confidence to put it all out there.”

Look close enough and you’ll see each of these attributes spanning the entire length of Pamela’s swim career like a string of pool lane floats.

Born in New Westminster in 1966 and raised in Delta, Pamela grew up in a very active and athletic family. Each of the Rai children—Pamela, Rajan, Michelle, and Sharon—were good swimmers from a very young age due to the fact their father, Harinder, who ran an excavating company, built a pool in their backyard himself so the kids could play and practice.

“That’s what got us into swimming,” Pamela said. “We were in that pool non-stop from May to September.”

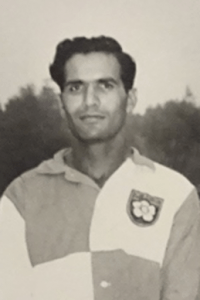

Both of Pamela’s parents valued sport and physical activity; her mother, Gladys, grew up skating on frozen ponds in Saskatchewan, while her father was one of Canada’s best field hockey players in the mid-1960s despite being denied a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. It was an incident of racial discrimination that should never have occurred and it would indirectly shape the swimming career of Harinder’s daughter Pamela.

When the first Canadian men’s national field hockey team was formed in 1962, Harinder—or ‘Pandit’ as he was nicknamed—was Canada’s star forward who scored our country’s first-ever international goal in Canada’s first-ever international match, versus the United States in Rye, New York, a 1-0 victory for Canada. The next year at an Olympic qualifying tournament in Lyon, France, he played a key role as Canada’s men’s field hockey team secured a place at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, the first time a Canadian men’s team had earned Olympic qualification.

However, just prior to the Olympics Harinder was wrongly removed from the squad by Canadian officials in favour of white team members. No official explanation was ever given to him.

“They wanted an all-white contingent,” said Pamela. “In 2019, at a BC Sports Hall of Fame event, 55 years after my dad’s removal from the Canadian National Field Hockey team, I ran into a player from that team and he was still upset about the decision.”

One of Harinder’s teammates at UBC in 1956-57 and on the BC provincial team and Canadian national team was Victor Warren, son of the great Harry Warren, who was inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame as a builder in 1990 for his field hockey contributions. Victor thought highly of Harinder as a teammate and a person and acknowledged he was wronged by officials.

“He was a great player and strong as hell,” Victor said in a recent email. “Pandit was certainly of the caliber to go on playing for Canada as he did in Lyon 1963. ‘Selectors’ were known to work in mysterious ways then.”

You’d think at its first Olympics a fledgling program like Canada’s would want all the help it could get, particularly from one of its best players, but racist decision making in this case won out. And ultimately it was to Canada’s detriment at the Games, as the team won only one match and scored just five goals in seven games. Although Harinder continued playing at the club level where he remains revered in the Indo-Canadian field hockey community to this day, he never again was involved with the Canadian national team after that.

“My dad didn’t actually tell us about it,” explained Pamela. “I had heard about it through other people later on. I think it was an area of emotional pain that he just put behind him. I think that was the reason why he put us into objective sports, like swimming, where the clock couldn’t discriminate.”

Robbed of an opportunity to compete for Canada at the world’s largest sporting event, rather than dwell on this negative experience, Harinder devoted himself to his children’s sport experience in order to ensure theirs was a positive one.

He continued coaching field hockey for years after, but after his son and daughters showed great promise in the backyard pool and later with the Surrey Knights swim club, Harinder immersed himself in that sport alongside his kids.

“He was so involved in swimming,” said Pamela. “He was club president and vice-president of the BC Amateur Swimming Association. I didn’t even know my dad had a regular job, that’s how much swimming stuff he did. He was a businessman too, so somehow he managed to work his livelihood in there. But just the driving us to workouts at 5am and again in the evening. Swim meets, four or five days long, all day on deck as meet manager or starter. So I think just seeing my dad in a leadership role and being a person of colour definitely shaped who I am today.”

It wasn’t long before Pamela was making waves as one of the best young swimmers her age not just here in BC, but across Canada and worldwide.

“Swimming just felt natural to me from a young age,” she said. “It still does. I’m not a very good land animal.”

She laughs at that last comment, but there’s some truth to it. Pamela, like most great swimmers, had the innate ability early on to glide through water rapidly.

“It’s a feel,” she explained. “It almost has to come from when you’re young. I rarely have seen someone have that feel at an older age if they were just getting into swimming. It’s a feel for the water that has to be nurtured over time, almost like learning a language when you’re young. When you learn it young, it’s easy and smooth.”

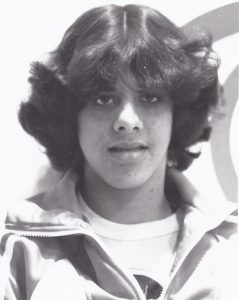

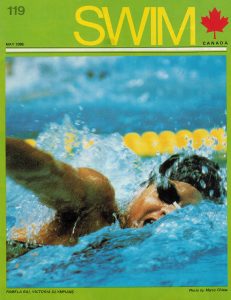

It might have appeared effortless, but that natural ability would be fortified by very powerful strokes under calm control honed from many hours and countless kilometers in the pool. Progressing rapidly, at age nine Pamela joined the newly-formed Hyack Swim Club based in New Westminster, where she was coached by Ron Jacks, embarking on a distinguished coaching career after recently retiring as a three-time Canadian Olympic swimmer and holder of multiple Canadian records. Jacks was known for pushing his young athletes hard, but Pamela thrived under his tough training regimen.

“You had to be a very disciplined person to be under Ron,” she said. “My father was a very disciplined person, so it wasn’t anything strange to me. Ron was definitely known for mileage, A LOT of mileage. More than runners would run. In really high training times or at a camp, we could do up to 20km a day over a couple workouts. That’s really high volume training. Plus, we did weight training and dry land cross training.”

When I comment on how impressive that volume of training is, Pamela laughed.

“Impressive…abusive? No. Coaches are just different now. For the better.”

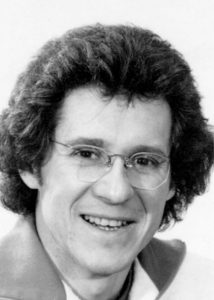

Later coaches like John Campbell, her age group coach, and Peter Vizsolyi, her coach at the University of Victoria, also made positive impacts on her career and development.

But the 1970s were a time when every swimming nation in the world was chasing the eastern bloc nations, like East Germany, who were churning out the fastest swimmers in the world behind a veiled doping program. Pamela saw this first-hand later on when competing for Canada internationally.

“I was at a meet in Japan in 1981 and I went into the women’s change room,” she recalled. “I thought I’d entered the men’s because I could only hear their deep voices when I walked in.”

One of the few ways countries competing clean like Canada could keep up was to load up on training volume. And on the whole, the strategy seemed to work. Canadian swimmers—and particularly those from BC—more than held their own internationally from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s regularly winning world championship medals, setting world records, and earning places on Olympic podiums. Pamela rose to prominence in the latter half of that period and stands as another key link in a long chain of strong BC swimmers from Mary (Stewart) McIlwaine to Elaine Tanner to Leslie Cliff, Wendy Cook, Donna-Marie Gurr, and Cheryl Gibson—all BC Sports Hall of Famers we should add.

“I feel like we were kind of like swimming’s classic rock,” Pamela summed up nicely. “Same kind of era. Great era for music. Great era for swimming.”

There are a lot reasons for this golden era in the water, but Beautiful BC had—and still has—one decided advantage over other provinces and regions.

There are a lot reasons for this golden era in the water, but Beautiful BC had—and still has—one decided advantage over other provinces and regions.

“We are the California of Canada,” Pamela reasoned. “Everywhere had a pool in the sixties. Every community.”

There was one more name from that roll call of the great BC swimmers from the 1960s and 1970s—Shannon Smith, who swam at the Hyack Club when Pamela was starting out and went on to win a bronze medal in the 400m freestyle as a 14-year-old at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. Just a few years older than Pamela, this made a massive impression on her.

“I obviously looked up to her,” she remembered. “Leslie Cliff was another. But also Olga Korbut and Nadia Comăneci, the great gymnasts from 1972. Gymnasts were also ones I always looked up to.”

The Olympics in general were something Pamela was thinking about from a young age.

“We were just glued to the TV every time the Olympics came on,” she remembered. “My dad had just such admiration for these athletes and I could just feel it when he watched them with intensity. That seed was definitely planted early on. Later it evolved, becoming a tangible goal that can be reached and not just a pipe dream.”

From an early age Pamela was devoting a huge amount of time working toward her ultimate swimming goal. She didn’t just inherit good athletic genes from her parents, but also the determination and discipline to do great things with that ability. As young as 10 years old she was travelling to California, one of the meccas of world swimming, where there were more swimmers in the San Francisco Bay area than all of Canada and she was wowing seasoned swimming observers, who considered her a lock to compete at the Olympics one day.

“I was such a great swimmer at the age of 10, if you took all the 10-year-olds in the world,” she said. “I was probably a better swimmer at age 10 than I ever was for my age group worldwide.”

By age 12 she was a member of the Canadian junior national team and by age 14 in 1980 she made the full senior Canadian national team. She would remain a member of the national team until retiring at the end of the 1986 season. Despite the many sacrifices she made to get there while away training and competing, Pamela feels she had a normal childhood—“whatever normal is.” Her sisters often tease her about this today.

“My sisters would say, ‘You were never at home!’” she laughed. “I missed a lot of family vacations and it’s a common comment they make: ‘Oh you don’t remember. You weren’t home!’ Like if a pet died. I’d just come home and our family dog wasn’t there. Those kind of things. I have these weird gaps of family life.”

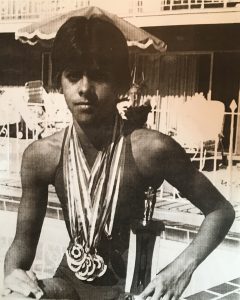

By the age of 14, Pamela had already set 16 Canadian age-group records and had won events in the US, Britain, and Germany. She then took the next step up to the senior level racing against the best of the best. At the 1980 Canadian Olympic trials in Toronto, she raced to a third-place finish in the 50m freestyle against much older competition. It didn’t qualify her for the Olympics, as top-two were selected, but after Canada and other western nations boycotted the Games, she was an add-on to the Canadian national team competing in various meets with other boycotting nations. From then on to the end of her career nearly seven years later Pamela was a constant on the national team.

In 1981 she won six medals at the Canada Games including a gold in the 50m freestyle. She also won her first medal at a senior international meet, a silver as part of the Canadian 4x100m freestyle relay team at the Tokyo International Meet.

In 1981 she won six medals at the Canada Games including a gold in the 50m freestyle. She also won her first medal at a senior international meet, a silver as part of the Canadian 4x100m freestyle relay team at the Tokyo International Meet.

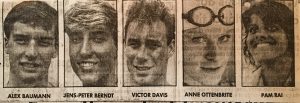

The next year she competed at the World Aquatic Championships in Guayaquil, Ecuador another major step up for the emerging 16-year-old as part of a Canadian team filled with world beaters.

“We were such a strong team at that time, both men and women, with swimmers like Alex Baumann, Anne Ottenbrite, and Victor Davis,” she recalled. “It was intimidating for someone so young. It was a learning opportunity, but totally exciting to be at a world championships. In some people’s eyes the world championships were considered greater than the Olympics because of the stronger, fuller fields in the Olympic boycott era.”

1983 brought Pamela her first of five career national titles, winning the 50m freestyle in 26.36 seconds, as well as another major breakthrough. She helped the Canadian women’s 4x100m freestyle relay team to a silver medal at the Pan American Games in Caracas, Venezuela.

“That was really exciting,” she recalled. “I remember vividly the outdoor pool they’d built for the Games, just incredible facilities. That was my first real international medal.”

The remarkable thing is that Pamela was producing world-class results while enduring heartbreaking circumstances at home. By 1982 her father Harinder was seriously ill, undergoing chemotherapy for leukemia. When not away training and competing, Pamela was at his bedside.

“It was very stressful for a lot of my training, the three years up to the Olympics,” she said. But even in deteriorating health, Harinder remained her biggest cheerleader. “He said ‘If you win Olympic gold, I’ll buy you a Delorean.’ I thought that car was the best thing ever.”

While it was a period of stress and pain, it also afforded Pamela the opportunity to learn more about her father and his upbringing from him. She came to appreciate what he had done and how much he had sacrificed for his family.

While it was a period of stress and pain, it also afforded Pamela the opportunity to learn more about her father and his upbringing from him. She came to appreciate what he had done and how much he had sacrificed for his family.

“I get messages even to this day telling me how great of a man my dad was, what a huge influence he was on their lives,” she said. “I’m pretty humbled by my dad’s story.”

It’s remarkable actually and worth sharing here as it helps explain where Pamela inherited some of the will, determination, discipline, and willingness to sacrifice to become a world-class athlete herself.

At age eight, Harinder, his twin sister, and older brother were orphaned in Punjab in northwestern India. They struggled to survive and when the violence and upheaval of the Partition of India began in the mid-1940s, in desperation Harinder and his siblings looked to escape to their estranged father’s in Port Moody, BC to start a new life in Canada.

“I recall a relative telling me that for his journey to this faraway land my dad was gifted with his first pair of shoes,” remarked Pamela.

In 1947, they left everything behind and journeyed by boat to Hong Kong. A good-natured merchant there gave them western clothes for the journey to the west.

The immigration rules of the day were racially weighted to favour the rich. If you came to Canada by boat—the cheapest mode of transportation—you were required to pass a medical exam in order to gain entry. But if you could afford a plane ticket and arrive in Canada by air, no medical test was necessary, the racially-loaded inference being if you had money, you must be healthy. While Harinder’s siblings passed the medical exam, he failed it likely due to a lung ailment and it appeared he would be left behind. That same merchant came to his assistance again by raising money for a plane ticket to Vancouver. At age 16 Harinder flew to Canada, while his siblings came by boat to San Francisco and then north by bus to Vancouver. They were held at the Peace Arch border crossing for two days despite having all the required paperwork.

Once in BC, Harinder went directly to work in a mill without finishing school. Later on at age 21, he attended Port Moody High School to finish his high school education. There were no adult courses in the mid-1950s, so as a full-grown man in a new country he sat in classes alongside 15-year-old students.

Later Harinder got a job in Regina. One day he was walking down the street there when someone noticing his skin colour stopped him and asked if he would like to be in a play the Regina Theatre was staging. They needed a black man for a bartender role, a hard role to fill in Regina in 1958 where the population was overwhelmingly white. Harinder was a good sport about it and agreed to play a Caribbean bartender with a Punjabi accent. Fortuitously that was how Harinder met Gladys Sikorski, a beautiful young x-ray lab technician from a Polish-Ukrainian family, who was helping out with the play. They married soon after and moved to BC to start a family.

In April 1984, three months before the Olympics in Los Angeles, the Rai family’s worst nightmare came true. Pamela and the rest of the Canadian swim team had just arrived in Hawaii for a training camp.

“We landed and got to the hotel,” Pamela recalled. “I remember the guy working at the desk had called my coach over sort of quietly and I knew. While I was on the flight to Hawaii my dad had died.”

Harinder Rai was just 52 years old. Pamela flew back to Vancouver two days later for the funeral, then flew back to Hawaii to continue the training camp.

“Whenever I competed he was in my spirit from then on,” she said. “I really had to delay my grieving, sort of compartmentalize. I just had to move on with what I had been working on from when I was very, very young.”

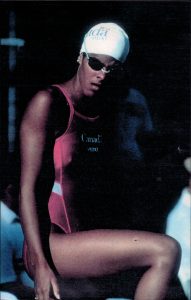

To cope, Pamela threw herself into her training and at the Canadian Olympic trials later that spring she won the 100m freestyle to qualify for the Olympics and not only fulfill her childhood dream, but also represent the spirit of her father who had been denied his opportunity at the Games twenty years earlier. What better tribute than to win a medal in his memory?

“That was the big dream, going to the Olympic Games,” she said. “Winning a medal was not even in my sights per se. It was a bittersweet time because my father had just passed away. He was my biggest cheerleader and supporter.”

Pamela wasn’t alone in Los Angeles though. Of course she had her Canadian teammates, but neighbours back home had pitched in and bought Pamela’s mother Gladys a flight and tickets to the Olympics so she could watch her daughter compete. Gladys was one of countless Canadians who journeyed south for the Games to support our athletes.

“There was such a huge contingent of Canadian people down there,” said Pamela. “The energy, you could definitely feel that there was huge support behind us.”

“There was such a huge contingent of Canadian people down there,” said Pamela. “The energy, you could definitely feel that there was huge support behind us.”

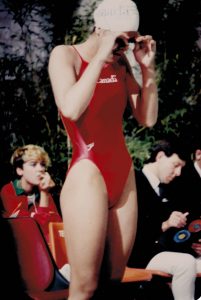

In the 100m freestyle, Pamela finished third in her heat in 57.41 seconds and just missed out on qualifying for the final by 11 hundredths of a second. She made the ‘B’ Final though and finished 12th overall for the event, often considered the toughest event to win in the sport.

Next up was the 4x100m freestyle relay where she helped Canada to a strong fifth-place finish in the final. And then came her final event, the 4x100m medley relay, with teammates Reema Abdo, Michelle MacPherson, and Anne Ottenbrite.

“We knew going in that we were medal contenders,” said Pamela. “We were very focused. We all swam our best.”

That they did. After qualifying third in the heats, in the final each of the four Canadian women improved their respective length split times (Pamela swam the freestyle leg in 56.64 seconds) as the team took bronze in a Canadian record time of 4 minutes 12.98 seconds, just a second back of the silver medal-winning West Germans. With that result, Abdo became the first woman of Yemeni heritage to win an Olympic medal, while Pamela became the first woman of Indian ancestry to do so. Carried by years of hard work in training, Pamela had made history. Inevitably, thoughts turned to her departed father, whose spirit carried her to the finish line.

“Indian immigrants didn’t often go into sports at that time, especially girls, but my father was such a feminist,” she said. “My sisters and I, we were brought up that we could do anything. We could be anything. I really appreciate that about him, breaking those traditional rigid roles and values. Growing up I definitely didn’t have any role models for Indian women or women of colour in sport.”

Those young female South Asian athletes that came after Pamela though now had one in her.

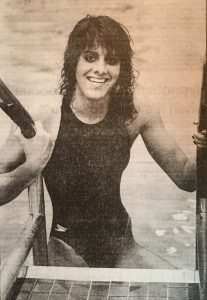

After the Olympics, Pamela moved to Victoria to attend UVIC and work toward her degree in sociology. She also swam for the Vikes, winning six CIAU national titles and setting five new CIAU records in two years. In 1985 she received the Canadian University Swimmer of the Year award and in 1986 UVIC bestowed its Athlete of the Year award on her. In 2019 she was inducted into the Canada West Hall of Fame.

That same year she competed at the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, Scotland finishing seventh in both the 100m freestyle and 100m butterfly, while helping the Canadian 4x100m relay team to a gold medal in a Canadian and Commonwealth Games record time of 3 minutes 48.45 seconds. It was nice to win a Commonwealth gold medal, but she harboured complex emotions about the history of the Commonwealth and how Britain had treated its colonial territories like India in the past.

That same year she competed at the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, Scotland finishing seventh in both the 100m freestyle and 100m butterfly, while helping the Canadian 4x100m relay team to a gold medal in a Canadian and Commonwealth Games record time of 3 minutes 48.45 seconds. It was nice to win a Commonwealth gold medal, but she harboured complex emotions about the history of the Commonwealth and how Britain had treated its colonial territories like India in the past.

“I remember wanting to put my medal in an envelope and mail it back to the Queen,” she laughed.

Pamela finished up the year competing at the World Aquatic Championships in Madrid, Spain where she finished 23rd in both the 100m freestyle and 100m butterfly, while helping the Canadian 4x100m freestyle relay team to a strong fifth-place finish. She returned home to Victoria to be named the city’s Athlete of the Year, quite the accomplishment considering the plethora of Olympic and national level athletes training out of Victoria at that time.

As the 1986 season came to a close, at the age of 21 Pamela made the decision to retire from competition. The grind of 13 years of international training and competition combined with the weight of her father’s illness and passing had taken their toll. She felt she couldn’t go on any farther in the sport.

“I just felt I didn’t have the support to be honest. I probably needed some help and support and my coaches were just not equipped to recognize or take that on. I was also supporting myself on my own and trying to pay for university. It is a regret of mine that I couldn’t have swam longer, but looking back on it, I was burnt out.”

She finished up as one of the best swimmers to ever come out of BC and has since used many of her skills and experiences as an athlete for a whole host of wide-ranging activities. She coached young swimmers for twenty years from the late 1980s until 2015. She moved to Nanaimo in 1992 and taught various high school subjects including social justice, math, English, and alternative education until just recently. After graduating in yoga studies from the Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy in Rishikesh, India, she has owned and operated Silent Motion Yoga, the only natural earthen yoga centre on Vancouver Island. She and her partner Regis spent nine years hand-sculpting and creating this sacred space to offer traditional yoga studies to people. As we covered off the top, much of her time recently is spent fighting to save our old growth forests. She also currently serves on the BC Games Society board of directors.

“I’m proudest of how I’ve used what made me good as an athlete to just keep learning and grow as a human with the same passion that I put into swimming,” she said. “I’ve been able to channel that and not become stagnant in one kind of paradigm.”

“I’m proudest of how I’ve used what made me good as an athlete to just keep learning and grow as a human with the same passion that I put into swimming,” she said. “I’ve been able to channel that and not become stagnant in one kind of paradigm.”

Rarely can I recall an elite athlete involving themselves in such varied interests and activities, any number of which on their own would be impressive. Collectively, it makes Pamela Rai one of the more remarkable individuals in this province’s sporting history.

And what of her 1993 induction into the BC Sports Hall of Fame? Leave it to Pamela to have an interesting take on that as well.

“I always say, ‘Oh hey, I’m in a museum! That’s how old I am!’ No seriously, it’s such an honour and it’s a legacy for me. It’s been a complete honour to be recognized for all those endless hours and years of work. Sometimes when I’m in Vancouver with a friend, we’ll go into the BC Sports Hall of Fame and it doesn’t even feel like me up there on the wall, just a whole other life. The recognition as an athlete and the credit really has to go to my family and teammates—without them, none of this would have been possible. But I’m honoured just to be in the company of so many amazing people.”

To learn more about Pamela Rai’s career, along with fellow BC Sports Hall of Fame Honoured Members Lori Fung, Robin Bawa, and Cleve Dheensaw, please see the May 2021 Asian Heritage Month Inspiring the Future webinar here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xh6Zxo2RZ6Y