Kelsey Serwa: A Golden Ski Cross Career – 2023 Inductee Spotlight

December 31, 2023By Jason Beck

If you were to poll British Columbians about what our most dominant sport or event internationally over the past 15 years has been, you’re bound to get a plethora of answers. Hockey. Soccer. Golf. Tennis. Basketball. Rowing. Athletics. Maybe a handful of others just for starters.

Unless prompted, few will answer ski cross. And that’s a crime because it really has been a remarkable run of unparalleled dominance. Whistler’s Ashleigh McIvor kicked things off by winning the inaugural Olympic ski cross gold medal at home at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. Four years later in Sochi, Whistler’s Marielle Thompson took the next Olympic gold medal in women’s ski cross, with Kelowna’s Kelsey Serwa taking home silver. In 2018 in Pyeongchang, Kelsey moved up one place on the podium taking Olympic gold and making it three-for-three for BC ski cross racers. The Olympic gold medal streak was snapped at Beijing 2022, but Marielle came close, taking home silver. On the men’s side Cultus Lake’s Reece Howden hasn’t medaled yet at the Olympics but does already have two World Cup Overall Crystal Globes to his name in his young career. Many will be watching eagerly in 2026 at the Milano-Cortina Winter Olympics to see which BC ski cross racer will take up the cause and add another gold, silver, or bronze link to this amazing chain.

Unless prompted, few will answer ski cross. And that’s a crime because it really has been a remarkable run of unparalleled dominance. Whistler’s Ashleigh McIvor kicked things off by winning the inaugural Olympic ski cross gold medal at home at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. Four years later in Sochi, Whistler’s Marielle Thompson took the next Olympic gold medal in women’s ski cross, with Kelowna’s Kelsey Serwa taking home silver. In 2018 in Pyeongchang, Kelsey moved up one place on the podium taking Olympic gold and making it three-for-three for BC ski cross racers. The Olympic gold medal streak was snapped at Beijing 2022, but Marielle came close, taking home silver. On the men’s side Cultus Lake’s Reece Howden hasn’t medaled yet at the Olympics but does already have two World Cup Overall Crystal Globes to his name in his young career. Many will be watching eagerly in 2026 at the Milano-Cortina Winter Olympics to see which BC ski cross racer will take up the cause and add another gold, silver, or bronze link to this amazing chain.

With the 2023-24 World Cup season well underway, it seems timely to look back at the career of Kelsey Serwa, the third BC woman to win an Olympic ski cross gold medal and earlier this year the third to be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame following McIvor (2012) and Thompson (2018).

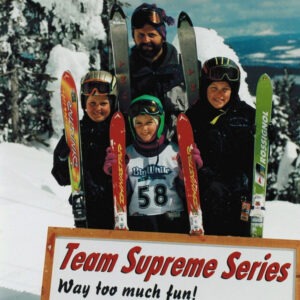

Born and raised in Kelowna, like it had been for the previous two generations of the Serwa Family, life for Kelsey and her siblings centered around skiing at Kelowna’s Big White Ski Resort.

Born and raised in Kelowna, like it had been for the previous two generations of the Serwa Family, life for Kelsey and her siblings centered around skiing at Kelowna’s Big White Ski Resort.

“We used to joke we were skiing before walking,” Kelsey said in an interview at her UBC condo with the BC Sports Hall of Fame earlier this year. “My parents would have me in their backpack to start. My sister Kristi would be off on her own, my brother Jason would be on a leash of some sort, I’m in the backpack, so you can just imagine, paint the picture. The mountain was always part of it.”

As the mountain always seems to have been for the Serwa family. Kelsey’s grandfather Cliff Serwa co- founded Big White with his friend Doug Mervyn, which first opened in December 1963 with one T-bar run. Later her parents owned and operated an excavating company, Serwa Bulldozing, which did a lot of the development work on the mountain. Big White just celebrated its 60th anniversary earlier in December.

founded Big White with his friend Doug Mervyn, which first opened in December 1963 with one T-bar run. Later her parents owned and operated an excavating company, Serwa Bulldozing, which did a lot of the development work on the mountain. Big White just celebrated its 60th anniversary earlier in December.

“Skiing runs in the family,” summed up Kelsey. “My grandpa and Doug discovered the area from hunting in the region and ski touring themselves and exploring. They realized this would be a great opportunity for a family resort close to Kelowna. Of course, there was a lot of criticism being so far out of town—45 minutes! People said it’s too far and no one would come. They have the credit for the vision of creating Big White. It’s a real nice place to call home.”

Growing up, Kelsey played a wide variety of other sports—everything from field hockey, basketball, volleyball, track and field to karate and even various forms of dance including Highland and ballet. She credits that wide experience in sport for later allowing her to make a career-defining switch which we’ll get to in a bit. But amongst all the other sports, there was always skiing and how she first got involved in racing is of course tied back to Big White.

When Kelsey was about five, the Big White Racers ski club approached her parents bulldozing company to see if they could dig the foundation for the new ski club cabin.

When Kelsey was about five, the Big White Racers ski club approached her parents bulldozing company to see if they could dig the foundation for the new ski club cabin.

“So sure enough, dad gets the excavator out there, he digs a hole and then they’re moving the club cabin and putting it back in,” Kelsey explained. “I guess the deal was they would exchange service for free ski lessons for myself, my brother, and my sister. My parents were like ‘Great deal, no problem! Take them!’ So that’s how we started out with racing because no one else in my family raced. We were the first ones.”

No one could have foreseen this simple exchange of services would send Kelsey flying down the course to a hall of fame career.

That came later though. From the very beginning, Kelsey just loved the thrill of racing. At first she was often one of the only girls and skied mostly with the boys on the Racers club team coached by Trevor Haaheim, Rebekah Smiley and Floyd Gniewotta, and on the Okanagan Zone team coached by Derek Trussler.

“I think that’s another thing that pushed me at the beginning,” she said.” I didn’t have any girls to hang out with, so I was literally chasing the boys.”

When she was a little older, more girls joined up and she bonded with them. She looked up to Canadian international freestyle moguls skier Kristi Richards from nearby Summerland.

It wasn’t long before Kelsey made her zone team, competing regionally, and then the BC alpine team under coach Nancy-Jo O’Neal, competing in races across the country. Kelsey then made the national development team at age 17 and began racing internationally in Europe. Her commitment to skiing meant she had far from your normal high school experience at École KLO Middle School and Kelowna Secondary. Kelsey completed much of her schooling by correspondence while she was away training and competing during ski seasons, often attending in person just for a month or two at the beginning and end of the school year. Somehow, she was able to juggle everything and graduated on time.

It wasn’t long before Kelsey made her zone team, competing regionally, and then the BC alpine team under coach Nancy-Jo O’Neal, competing in races across the country. Kelsey then made the national development team at age 17 and began racing internationally in Europe. Her commitment to skiing meant she had far from your normal high school experience at École KLO Middle School and Kelowna Secondary. Kelsey completed much of her schooling by correspondence while she was away training and competing during ski seasons, often attending in person just for a month or two at the beginning and end of the school year. Somehow, she was able to juggle everything and graduated on time.

In her early years Kelsey only raced alpine events, her favourites being giant slalom and downhill. Her rise in the mid-2000s timed perfectly with the influx of increased funding funneled into Canadian sport after Vancouver won the right to host the 2010 Winter Olympics. There suddenly were many more opportunities and programs for skiers of her generation. At the same time there was also a really strong group of racers her age within her zone that she found herself chasing.

“I got to ride the coattails of the funding and these other girls from my zone that were better than I was,” admitted Kelsey. “So I was always pushing myself to catch up to them. But I could see myself in their race boots essentially.”

Eventually Kelsey progressed to a point where it didn’t appear she could go any farther with alpine racing. It all came to a head the winter after she graduated from high school, struggling mightily with her racing as nothing seemed to be working out for her.

“We went over to Europe which was incredible, but we were chasing slalom races,” she recalled. “There happened to be room at each race for six Canadians and I was always number seven. So I was pretty much just spectating, paying to watch, didn’t get to race, and didn’t have the opportunity to showcase my skills.”

“We went over to Europe which was incredible, but we were chasing slalom races,” she recalled. “There happened to be room at each race for six Canadians and I was always number seven. So I was pretty much just spectating, paying to watch, didn’t get to race, and didn’t have the opportunity to showcase my skills.”

At a critical age where Kelsey needed to be on the hill getting elite level experience, it was a case of being so close yet still so far. She found herself at a crossroads almost to the point of thinking about trying something else. But then the breakthrough arrived out of nowhere.

“One of my previous coaches was like, ‘Oh, have you seen this sport ski cross?’”

Kelsey had seen this new freestyle discipline at nationals in Whistler and on TV but had never attempted it.

“I thought, ‘Whoa! That’s gnarly! Like crazy!’”

She decided to give ski cross a try for the first time at Canadian nationals in Rossland at the end of the 2007-08 season.

“So I just pulled out of the gate, nervous as heck, all the national team members are up there,” she recalled. “I went off this feature called ‘The Wu Tang” and I didn’t know how to do it. It was pretty much two back-to-back quarter pipes and then about a meter landing on top that you’re supposed to jump over and clear. I go straight up and straight down. I think I smashed my face on my knee. I was like, ‘Oh god, this is brutal!’ I remember my back being really tired after, just using all the muscles in your body in a different way that you weren’t used to.”

“So I just pulled out of the gate, nervous as heck, all the national team members are up there,” she recalled. “I went off this feature called ‘The Wu Tang” and I didn’t know how to do it. It was pretty much two back-to-back quarter pipes and then about a meter landing on top that you’re supposed to jump over and clear. I go straight up and straight down. I think I smashed my face on my knee. I was like, ‘Oh god, this is brutal!’ I remember my back being really tired after, just using all the muscles in your body in a different way that you weren’t used to.”

You may not have known it from Kelsey’s description of that first race, yet she was immediately hooked on ski cross.

“It was exciting and fun, but I think what drew me to it too, was all the unexpectedness. Not only do you have to navigate yourself all around this track, but there are three other people racing around you. Like no two runs are the same.”

Kelsey messaged national ski cross coaches all summer after that trying to get onto the team: “How do I join? How do I get to be part of this team? I’ll pay my way. I don’t care! I’ll figure it out. So that was the start of my ski cross journey.”

It might have seemed unthinkable after that first race but in less than two years Kelsey would be considered one of the best up-and-coming ski cross racers in the world.

Once Kelsey had a place on the national ski cross team, more established racers Julia Murray and Ashleigh McIvor took her under their wings and showed her the ropes. She also learned a lot from the Canadian men’s team racers. One of the unique things about ski cross is that the men and women travel and race together at the same events around the world whereas in alpine men’s and women’s tours and events are separated. This was actually how Kelsey reconnected with childhood friend and future husband Stan Rey, who was a member of the Canadian men’s ski cross team from 2009-12 before becoming a professional freeskier. They were married in 2019.

Kelsey also gives a lot of credit to the various national coaches who helped her throughout her ski cross career, starting with Willy Raine and later Brent Kehl, Eric Archer, and Stanley Hayer, the latter a former national teammate who coached Kelsey after retiring.

Kelsey also gives a lot of credit to the various national coaches who helped her throughout her ski cross career, starting with Willy Raine and later Brent Kehl, Eric Archer, and Stanley Hayer, the latter a former national teammate who coached Kelsey after retiring.

The timing of Kelsey’s leap into ski cross couldn’t have been better. Beginning with the 2008-09 season, she essentially had a little over a year to figure out the sport before ski cross made its debut at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. Her goal from the outset was to make the Canadian team to compete at the Olympics in her home province.

“When I told my parents I was retiring from alpine racing, my mom was like, ‘Oh great, she’s going to go to university and get a degree and be a contributing member of society,’ Kelsey laughed. “But I was like, ‘No! Skiing still, just looks a little bit different.’”

It wasn’t long before Kelsey could justify she’d made the right decision to switch skiing disciplines mid-career. She soon made the Canadian team and qualified for the 2010 Winter Olympics. Then just a week before the Games in Vancouver opened, she won her first World Cup race.

With the ski cross events at Cypress Mountain in the second week of Vancouver 2010, Kelsey and her teammates had the opportunity to go out and experience the Games a bit, watching other events and being the ultimate cheer squads for Canadian teammates. When it came time for her chance to compete, Kelsey had plenty of family present to watch her races.

The course at Cypress was very technical, which combined with every kind of snow possible, made for very challenging conditions. Add to that a lot of collective nervousness among all competitors, nearly all making their Olympic debut.

“I remember a lot of nervous, quiet energy in the start area,” Kelsey said. “Normally it’s quite buzzing with activity, people joking around. But it was just strange seriousness.”

At least the Canadian competitors had the hometown crowd on their side. When it was Kelsey’s turn to race, it was a moment she’ll never forget.

“I remember standing in the start gate and being able to hear the crowd from the bottom cheering us on. That’s pretty cool. That had never happened before. To stand in the start gate and hear a roaring crowd at the base of the mountain cheering you on when you’re at the top. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Uhhh, biggest event, probably going to choke! Or I can just stay calm and execute my plan.’ I used that as a cue to re-center, re-focus.”

Riding on the roar of the crowd and continuing her strong form from the World Cup season, Kelsey qualified fourth overall before winning her first round and quarterfinal heats. Everything seemed to be coming together as she led her semifinal heat with just two more turns and a couple jumps to go. A place in the Big Final and a chance at an Olympic gold medal was right there. Then she hit some fresh snow on the track, slowing her down just enough for two competitors to pass her on the final turn. Kelsey was naturally devastated and the ten-minute chairlift ride back up the mountain seemed to take forever. But she recovered and ended up winning the consolation Small Final to finish fifth overall. Not bad for her Olympic debut just a couple of years after taking up the sport.

“And I had a front row seat to watch my teammate Ashleigh win gold, which was…I’m getting goosebumps just reimagining it. That was the coolest. I think where I was in my career, that’s exactly what I needed.”

Seeing McIvor claim the sport’s first-ever Olympic gold medal was both motivation and realization for Kelsey: if Ashleigh can do it, maybe I can too.

The 2010-11 season that followed was a breakthrough for Kelsey. After winning a bronze medal at the Winter X Games the previous season, this year she moved up on the podium to claim her first of two career Winter X Games gold medals (the second in 2016). The gold came at a price as she crashed hard at the finish line.

“I landed very, very hard,” she recalled. “I was leading the race and we were coming up to this final jump and we were going way faster than we had been in training. I remember thinking, ‘Oh I should probably slow down.’ But then I also remember thinking, ‘Ah, but I’m in the lead and I don’t want to give that away!’ So I did a quick speed check, not enough to do anything, probably if anything it put my weight into the backseat so I wasn’t in an ideal position to absorb this jump. I flew through the air slowly rotating backwards, bottom dropped, spin, came to a stop totally winded and that feeling of you cannot breathe. You cannot inhale. It’s like a prolonged exhale. People were running over like ‘Oh my god! Is she okay?!’ I was just asking ‘Did I win?’ with the first breath I had. So that was great.”

Kelsey ended up with two compression fractures in her spine, a badly bruised tailbone, sprained MCL in her elbow, strained thumb, and a busted-up nose.

Kelsey ended up with two compression fractures in her spine, a badly bruised tailbone, sprained MCL in her elbow, strained thumb, and a busted-up nose.

“All this from this one crash. But totally worth it. Wouldn’t take it back for anything,” she laughed.

And then just four days later the world championships were at Deer Valley Resort in Utah.

“I could not sit down. My tailbone was so painful. My back was so seized up.”

Kelsey missed all of training that week and was on painkillers to manage her injuries. To add to the stress of the situation, she had to obtain a therapeutic use exemption as the codeine in the painkillers was a banned substance. Canadian men’s teammate and future husband Stan Rey gave Kelsey his Go-Pro helmet cam footage from the Deer Valley course. Kelsey watched it over and over from the couch, learning every turn and jump, as she never was well enough for any training runs. Somehow the medical staff patched her up enough that she was back on skis for qualifying and riding on little more than adrenaline she made the final. That alone was an accomplishment, but there was more.

“I showed up on race day still totally broken. Then won that race and my back didn’t hurt anymore,” she laughed. Funny, a world championship title will do that.

By this point in her career, Kelsey was well used to the unique training rhythm of the sport. In the summers, the average week would include hitting the gym five mornings for three-to-four-hour workouts. In addition, three days a week they’d work on gymnastics training like trampoline or floor work. And six days a week there was some sort of cardio in the afternoons, maybe a few hours of road or mountain biking, maybe BMX or pump track biking.

“So anything goes,” said Kelsey. “We were never a sport that was like, ‘Oh, you’re not allowed to engage in this activity’ for risk of injury because our sport was probably the riskiest.”

Asked what she thought about while racing, the answer perhaps not surprisingly is that there isn’t much time to think.

Asked what she thought about while racing, the answer perhaps not surprisingly is that there isn’t much time to think.

“In ski cross you need to respond to whatever’s going on around you,” she explained. “You can have your Plan A, Plan B, Plan C, but at the end of the day it’s more about your ability to adapt whether you’re leading or whether you need to make a pass, whether you’re playing offense or defense essentially. Sometimes too you can’t control other people running into you, right? It’s such a dynamic sport that you just need to stay focused in the moments and have your small cues that will re-center you, to have these zones that you’ve made in your mind of passing opportunities. Setting things up maybe a few turns in advance, knowing where to create a little bit of space so you can capitalize on that draft coming into a corner. That all goes into the preparation and planning so on the course it’s second nature, so you don’t have to think, you just act.”

One of the things that set her apart was her willingness to put in the work necessary to get to the next level.

“I was never the best as an athlete. I was never the strongest, never the fastest growing up. But I think because of that I had a good work ethic. I was always playing catch-up. One of my strengths is dedication, persistence, grittiness. I came back from a few significant injuries with tight timelines.”

Which brings us to the next chapter in Kelsey’s story. In January 2012, she was leading the World Cup overall standings when she suffered a ruptured ACL in her left knee after getting tangled up with another competitor in a World Cup race. She rehabbed all summer and returned to competition for the 2012-13 season at full health and was soon flying again. Later that season at the world championships in Voss, Norway disaster struck again when in Kelsey’s own words she “got a little greedy” and landed on a competitor’s skis in front of her. She caught an edge, flew off a jump and landed in a spin and twist. She re-tore the ACL in her left knee and her season was done.

Which brings us to the next chapter in Kelsey’s story. In January 2012, she was leading the World Cup overall standings when she suffered a ruptured ACL in her left knee after getting tangled up with another competitor in a World Cup race. She rehabbed all summer and returned to competition for the 2012-13 season at full health and was soon flying again. Later that season at the world championships in Voss, Norway disaster struck again when in Kelsey’s own words she “got a little greedy” and landed on a competitor’s skis in front of her. She caught an edge, flew off a jump and landed in a spin and twist. She re-tore the ACL in her left knee and her season was done.

“It was hard to go from feeling unbeatable and everything coming together to just down and out.”

The worst part was the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi were less than a year away. Kelsey went to work rehabbing once again, doing everything just to give herself a chance to qualify for the Olympics, which given the timeline and her injury seemed remote to most. Somehow she got herself healthy enough to return to competition and selectively chose her races, trying to do just enough to earn her Olympic spot without doing further damage to her knee.

“My knee was angry,” she remembered. “Skiing was painful.”

It was a gamble, but it paid off, qualifying for Sochi albeit “maybe at 80%” health. Because she hadn’t had the normal preparation time and still wasn’t fully recovered from the injury, Kelsey felt uncharacteristically jittery and nervous in the Sochi start gates. Her parents and grandparents came to Russia to watch, which helped, and she felt fortunate that she had her young Canadian teammate Marielle Thompson to watch, who was skiing great. Kelsey seemed to feed off that and she finished first in qualifying with Marielle third. Both won their respective first round and quarterfinal elimination heats and qualified for the Big Final.

It was a gamble, but it paid off, qualifying for Sochi albeit “maybe at 80%” health. Because she hadn’t had the normal preparation time and still wasn’t fully recovered from the injury, Kelsey felt uncharacteristically jittery and nervous in the Sochi start gates. Her parents and grandparents came to Russia to watch, which helped, and she felt fortunate that she had her young Canadian teammate Marielle Thompson to watch, who was skiing great. Kelsey seemed to feed off that and she finished first in qualifying with Marielle third. Both won their respective first round and quarterfinal elimination heats and qualified for the Big Final.

Kelsey and Marielle had grown used to working together in races and there was no better example of that than the first turn of the Big Final in Sochi.

“I was just behind Marielle but on her inside, so I let her know,” Kelsey recalled. “‘Hey, I’m on your inside!’ She gave me enough room to fit around the gate. Whereas if it was a competitor, you wouldn’t hesitate to cut in. It was neat to have that teamwork on the track. You’re still racing for medals as individuals, but that was cool to follow her down into the finish line.”

Marielle took the Olympic gold, while Kelsey claimed silver.

“That was really cool. It was definitely beyond my expectations. It was really neat to celebrate that with Mar. Glad she won and we got to enjoy our anthem together. My first reaction when that medal went around my neck was ‘Holy crap, this thing’s heavy!’ It took my breath away and made me appreciate all the people that had invested in my sporting career to make this happen. It was also relief, like ‘Good, all the work was worth it.’ We all got this great return on investment.”

Immediately after the race, Kelsey was also already thinking about how to top this silver medal effort. Ashleigh McIvor was commentating for the CBC and ran over to Kelsey in the finish area to give her a hug.

“She said, ‘I’m so proud of you!’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, but we both know it’s the wrong colour.’ She’s like, ‘I know!’ She’s the only person I could have said that to. It just speaks to the fact I wasn’t going to settle for silver, that there was still work to be done and a bigger goal to be achieved. I wanted what Ashleigh had. I wanted what Marielle now had. So, my eyes were still set on that gold.”

Four years out and Kelsey was already focused on winning the gold at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. Things were going to plan until December 2016 when in a race she landed hard on a double-jump and tore cartilage right off the bone in her knee. With the Olympics just 13 months away, she underwent a complex ‘cartilage-transplant’ procedure to replace the cartilage in her knee with good cartilage from elsewhere in her body.

Four years out and Kelsey was already focused on winning the gold at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. Things were going to plan until December 2016 when in a race she landed hard on a double-jump and tore cartilage right off the bone in her knee. With the Olympics just 13 months away, she underwent a complex ‘cartilage-transplant’ procedure to replace the cartilage in her knee with good cartilage from elsewhere in her body.

“That was the hardest surgery to recover from because I was non-weight-bearing for six weeks. On crutches in the middle of winter, while on campus at UBC Okanagan, crutching my way through classes. And no impact for six months. And I was doing my recovery by myself in between classes.”

With the upcoming Olympics in the back of her mind, Kelsey tried pushing her recovery timelines a bit, but she often just had to be patient.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I’m allowed to walk now, maybe I’ll go for a small ski tour on groomed runs at the end of the day.’ But I remember sliding down the hill and it hurt sooo bad and I started to think I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to get back on snow and feel good again. There was a lot of ups and downs for sure.”

One of the things that helped her through was training with Canadian national teammate Brittany Phelan.

“We created a really strong bond going back a few years prior to 2016. Brit came onto the team and we just clicked right away. She was my all-time training partner turned into best friend. We were on our own program together and needed similar things. We operated totally differently but it was a nice mesh. I was weak in areas where she was strong, so we filled in each other’s gaps, kind of thing, which is really cool. It was just a great working relationship, friendship going into those Games.”

Kelsey managed to recover enough from the surgery to begin competing again at the start of the 2017-18 season. The race results she and Brittany were producing were solid if unspectacular, usually finishing comfortably in fifth to eighth, once in a while making a Big Final and finishing third or fourth.

“We were not favourites by any means,” emphasized Kelsey. “But we were celebrating our own little victories.”

“We were not favourites by any means,” emphasized Kelsey. “But we were celebrating our own little victories.”

Both managed to do enough to qualify for the Olympics in Pyeongchang. Kelsey knew it was her last Olympics and was publicly open about that fact, which actually took a lot of pressure off her. She wanted to enjoy these Games, capitalize on this last opportunity, but also have fun. Which was easy with Brittany. It meant both were in a great place mentally going into the Games. Yes, there was lots of goofing off, but Kelsey and Brit also worked hard and were ready. Yet no one expected either of them to win. That didn’t bother either of them.

“Being able to stand beside each other in the start gate and you know that that person has your back and you’ve got their back and they’re as much invested in your success as you are in theirs. It was like we had already won before the gate even dropped.”

Anything good that happened after that was a bonus.

Barely recovered from her own serious knee injury, Marielle Thompson qualified first with Canadian teammates Kelsey and Brit second and third. But in the first elimination heat, Marielle fell and was eliminated. Meanwhile Brit and Kelsey won their heats to move on.

Then in the warm-up before her quarterfinal heat, Kelsey tweaked her back. She had battled with it in the autumn a little, but it settled down until now coming out of nowhere.

“I was like, ‘Oh @%$^, we’ve got ten minutes until go-time!’”

There was a heater blasting hot air in the start area, so Kelsey took off her race suit and back brace, stood in front of the heater, and just hoped the heat would help.

“I didn’t say anything to anyone about it. I could still feel it, but I got into the start gate and was determined to see how far I could go.”

Her back ached all the way down the course and she felt it in the landing of every jump, but she somehow still managed to finish first. Brit was her quarterfinal as well. Canadian team officials scrambled to get a physio up to work on Kelsey to try to get her through the next race, the semifinals.

“This is the race I usually get most nervous for because it determines who moves on to the Big Final. So I had a good start and was ahead when all of sudden I felt someone come up beside me a third of the way down the course. I thought, ‘Shoot, this is it, getting passed.’ And then I see green skis. ‘Oh! Brit’s on green skis!’ And I see Brit rip by and I’m like, ‘Yeah! Go Brit!’ So I got to chase her going down to the finish line and what a cool feeling that was, a celebration before the Big Final.”

Brittany won the semifinal heat with Kelsey just behind in second, so both moved on to the Big Final with Olympic medals now on the line.

“I happened to have a good start and led top to bottom,” remembered Kelsey. “Brit had to battle her whole way down the track and she made a double-pass on the second last turn and went from fourth to second. Yeah, it was incredible. She jokes that she let me win because she knew it was my last Olympics. I’m like, ‘Thank you, that’s so kind of you.’ But yeah, no doubt in my mind if she didn’t get hung up behind the Swedish and Swiss girls she would have passed me like she had in the round before. It was neat how it all worked out.”

Canada—and BC—had won the Olympic women’s ski cross for the third Games running.

“It felt insane. Really unbelievable. Brit and I had already won [finding each other as best friends]. The medals were just the cherry on top, the bonus part. To cross the line, just the overwhelming thrill and joy and happiness and knowing my parents and grandparents were in the stands, my husband Stan had actually surprised me two days before, flew out, so he’s there too. He comes running out into the finish area, gives me a big hug. I get rushed by the Canadian team. It was really neat.”

“It felt insane. Really unbelievable. Brit and I had already won [finding each other as best friends]. The medals were just the cherry on top, the bonus part. To cross the line, just the overwhelming thrill and joy and happiness and knowing my parents and grandparents were in the stands, my husband Stan had actually surprised me two days before, flew out, so he’s there too. He comes running out into the finish area, gives me a big hug. I get rushed by the Canadian team. It was really neat.”

And for the second consecutive Winter Olympics, when O Canada was played up on the medal podium for the women’s ski cross, it was for two Canadians—Kelsey and Brit this time.

“Yeah. For us. For Brit and I. One of the things I told Brit in the finish area right after the race: “We won the Olympics!” It wasn’t that I came first and she came second. ‘WE won.’”

As the third straight British Columbian woman to win the Olympic ski cross gold medal, it begs the question: why are BC and Canada so dominant in this event?

“I think the environment, where we grow up, the people around us, plays a big role. Timing. Having great people to look up to and get taken under their wings. Ashleigh took me under her wing. I took Marielle under mine. A lot of things need to align. But Canada’s been the best ski cross team in the world seven or eight times for a reason. We push each other. We train together. We race together. Best coaching staff and ski technicians in the world. Supportive community. A little rough around the edges, like just the perfect amount. Maybe it’s the water?! [laughs] I feel very proud to be part of this prestigious group.”

wings. Ashleigh took me under her wing. I took Marielle under mine. A lot of things need to align. But Canada’s been the best ski cross team in the world seven or eight times for a reason. We push each other. We train together. We race together. Best coaching staff and ski technicians in the world. Supportive community. A little rough around the edges, like just the perfect amount. Maybe it’s the water?! [laughs] I feel very proud to be part of this prestigious group.”

Nothing changed too much for Kelsey after winning the Olympic gold medal except maybe the opportunities it offered.

“The part I enjoy most is the chance to share the medal with people. Doesn’t matter what age you are, everyone recognizes the significance of an Olympic medal. It’s just cool to see it in their hands and maybe that can inspire somebody.”

She paused before continuing.

“I mean, school or exams or getting a job after are just as hard whether you have an Olympic medal or not. Maybe the medal gets you in the door, but you still have to follow it up with being a confident person. It just feels like a nice cherry on top of a great career.”

“I mean, school or exams or getting a job after are just as hard whether you have an Olympic medal or not. Maybe the medal gets you in the door, but you still have to follow it up with being a confident person. It just feels like a nice cherry on top of a great career.”

Kelsey had planned to retire after the 2018 Olympics, but Brit convinced her to stick around for one more year “because we were having so much fun.”

It allowed Kelsey to essentially do a victory lap of the World Cup circuit with her best friend, teammates, and competitors and go out on top. Very few are granted a gift like that.

“I’m glad I did. It wasn’t my most stellar season, but Brit and I got on the podium together in Sweden, which was fun to have that memory together. Pressure was off, but I still showed up to win every race. It wasn’t the end of the world not winning. So I was fortunate in that I got to choose my exit strategy, my exit plan and the timing. It was well-supported by coaches and sponsors. Everything was out in the open. I wasn’t forced out due to injury or not performing well. I don’t think everybody is so fortunate to have that in their career. Sometimes that decision is made for us as athletes.”

Kelsey retired after 11 seasons on the Canadian national team (2009-19) as one of the most decorated ski cross racers in history: three Olympic appearances, two Olympic medals including one gold, the 2011 world championship, three Winter X Games medals (two gold, one bronze), and eight career FIS World Cup tour victories along with 20 podium finishes.

In retirement, Kelsey focused on finishing her schooling to become a physical therapist. In late November, she graduated at the top of her class from the UBC Masters of Physical Therapy program. She is now working as a physiotherapist at Back in Action Physiotherapy and Massage in Whistler. Kelsey has also been providing on-air analysis and commentary on FIS World Cup ski cross events for CBC Sports.

In retirement, Kelsey focused on finishing her schooling to become a physical therapist. In late November, she graduated at the top of her class from the UBC Masters of Physical Therapy program. She is now working as a physiotherapist at Back in Action Physiotherapy and Massage in Whistler. Kelsey has also been providing on-air analysis and commentary on FIS World Cup ski cross events for CBC Sports.

With such a decorated career at the highest levels of her sport, Kelsey’s BC Sports Hall of Fame induction will no doubt be the first of many inductions to come.

“It feels like a huge honour. Yeah, I thought this was reserved for people much later in their lifespan, so to be inducted in my thirties, it’s an incredible honour. It’s a really strong induction class and to see the people who have come before me and to see the people who will come after as well, it’s not a small feat by any means. And once you’re inducted into the class, you’re there forever. Not many things are forever, but that’s something I’m really proud of.”

As part of the Class of 2023, Kelsey Serwa was formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Athlete category at the annual Induction Gala held June 1, 2023 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.