Eleanor (Young) Stonehouse: Rebel with a Racquet – 2023 Inductee Spotlight

March 29, 2023By Jason Beck

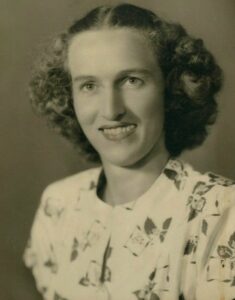

During her impressive tennis career through the 1930s until 1948, Eleanor (Young) Stonehouse was certainly a pioneer.

With a powerful forehand and an aggressive, net-charging style that foreshadowed the play of future women’s players, she won top tournaments all over the country. She even made it all the way to Wimbledon at a time when few top Canadian players dared journeying beyond regional tourneys. She was arguably the best women’s player Canada had ever seen to that point and a barrier breaker in more ways than one.

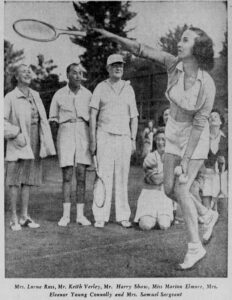

And that’s the thing that isn’t immediately obvious when sifting through photos of Eleanor on the court, often smiling and looking prim and proper. Make no mistake, Eleanor (Young) Stonehouse was something of a rebel at a time and in a sport where that was definitely unique.

“She just did what she wanted to do,” said her son Jim Stonehouse in a recent interview. “She was outdoorsy. She just liked to do things. If it was new, she would just do it. She just did whatever she wanted to do. Now you probably wouldn’t call her a rebel because everyone’s sort of a rebel today, but back then that was pretty rare.”

What was also rare was Eleanor’s love for tennis. It comes across in the photos of her career. In most, she is just beaming with racquet in hand. She truly loved the sport. And to get to the level she did, you have to love it. Few rose as high as Eleanor and along the way she changed the game for those who followed her.

Born and raised in North Vancouver, Eleanor’s family first lived on East 6th Street before later building a beautiful house which Eleanor largely grew up in that still stands today on the corner of the Grand Boulevard and 18th Street in North Van. It was on the side lawn of this home that Eleanor was first taught to play tennis by her father, E.V. Young, widely known as the hard-working secretary of the BC Lawn Tennis Association in the 1920s and 1930s. He was also a long-time Vancouver Lawn Tennis Club player, umpire, and tournament manager, as well as a noted thespian, one of the founders of Stanley Park’s Theatre Under The Stars, and a host of a late-night CBC Radio program. In a slow and methodical manner, he gradually taught Eleanor the finer points of tennis shot by shot.

Born and raised in North Vancouver, Eleanor’s family first lived on East 6th Street before later building a beautiful house which Eleanor largely grew up in that still stands today on the corner of the Grand Boulevard and 18th Street in North Van. It was on the side lawn of this home that Eleanor was first taught to play tennis by her father, E.V. Young, widely known as the hard-working secretary of the BC Lawn Tennis Association in the 1920s and 1930s. He was also a long-time Vancouver Lawn Tennis Club player, umpire, and tournament manager, as well as a noted thespian, one of the founders of Stanley Park’s Theatre Under The Stars, and a host of a late-night CBC Radio program. In a slow and methodical manner, he gradually taught Eleanor the finer points of tennis shot by shot.

“She started playing at the age of 11 and for the first year we concentrated on her footwork and forehand ground shot,” E.V. said in 1931. “The next year she began to develop a backhand. Last year she added the volley, and this year the chop shot and net play. The result of this policy of developing and perfecting one shot at a time has been that she is now well armed at all points, and the features of her game are accuracy in placing and length. At the start we did not allow her to attempt to hit the ball hard, but to concentrate on length and accuracy, and each succeeding year as height and weight have increased she has, almost unconsciously, added pace and sting to her shots.”

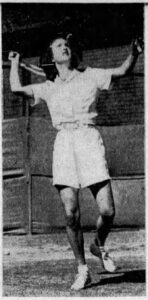

Eleanor later became known as one of the hardest hitters of her era with a powerful forehand that blew past many opponents. Kay Staples, who played beside Eleanor as her doubles partner in the late 1930s, said Eleanor “hit her big forehand inside out” similar to the way the great Steffi Graf did many years later. Another who played with Eleanor was one-time Tennis Canada president Jim Skelton, who also highlighted Eleanor’s power to the North Shore Outlook’s Len Corben in 2005.

“Eleanor had a big forehand,” Skelton related. “It wasn’t a stylish forehand but it was really strong. She just clobbered it. Very solid. She wasn’t a fast person on the court because she was not exactly built for speed. She wouldn’t impress you unless you were on the other side of the net and receiving some of her forehands. She was sort of stocky, but she just had a really big forehand and that carried her. She took a mighty swipe at the ball with her forehands.”

“Eleanor had a big forehand,” Skelton related. “It wasn’t a stylish forehand but it was really strong. She just clobbered it. Very solid. She wasn’t a fast person on the court because she was not exactly built for speed. She wouldn’t impress you unless you were on the other side of the net and receiving some of her forehands. She was sort of stocky, but she just had a really big forehand and that carried her. She took a mighty swipe at the ball with her forehands.”

In that era, most Canadian women stayed along the baseline and returned shots. Eleanor was one of the first to charge the net for overhead returns or volleys like the American players, which made her an immediate force. But all of that came later, as early on like so many young athletes learning a new sport, she was just trying to figure the game—and herself—out.

“I started playing in junior tournaments when I was about 12, and at first I didn’t have much confidence when I played against the other girls,” Eleanor told Mary Ormsby of the Toronto Star in 1993. “There was this one girl in particular who was a little older and I always thought she would beat me—and she did. Eventually, I did beat her and I remember it was a great feeling.”

Eleanor attended Crofton House private school in Vancouver, which meant catching a ferry at the foot of Lonsdale each morning and a long return trip each evening, the only way to cross the water in those days from the North Shore before the Lions Gate Bridge was built and with the original Second Narrows Bridge closed for several years due to a marine collision. She had originally played mostly at the small North Vancouver Tennis Club but later in her teens she often practiced after school at the Vancouver Lawn Tennis and Badminton Club where her father was a member, joining him for structured lessons very much in the English tradition that was his background.

“I think that was why she got better at tennis because her father was so strict with teaching her,” said her son Jim.

Eleanor also took up badminton in her teens at the suggestion of a friend, who thought it might help her improve her backhand. Soon she was winning city championships in both tennis and badminton. In fact, one of the more underrated parts of Eleanor’s career is how strong her badminton game became. In 1941 and 1942, she won the BC provincial badminton title in each of singles, doubles, and mixed doubles. In 1941, she defeated the reigning US national champion, Evelyn Boldrick, to win the Inland Empire Badminton Tournament in Spokane, Washington. Eleanor was never able to capture a Canadian badminton title but was consistently ranked among the top five women’s singles players in the country for many years.

Eleanor’s big breakthrough in tennis came in 1934 at the age of 18. After reaching the final of the BC provincial championship before losing to Gussie Raegener of San Francisco, she travelled across the country by train to Toronto to play in the Canadian National Tennis Championships. After winning the Canadian junior singles title, the next day in the open singles final she faced Caroline Deacon in an all-North Vancouver match-up on the opposite side of the country from their homes on the North Shore. Deacon was a few years older than Eleanor and having a stellar season herself having won several city tournaments around BC and ultimately prevailed 7-5, 6-3 coming from behind down 5-3 in the first set.

Eleanor’s big breakthrough in tennis came in 1934 at the age of 18. After reaching the final of the BC provincial championship before losing to Gussie Raegener of San Francisco, she travelled across the country by train to Toronto to play in the Canadian National Tennis Championships. After winning the Canadian junior singles title, the next day in the open singles final she faced Caroline Deacon in an all-North Vancouver match-up on the opposite side of the country from their homes on the North Shore. Deacon was a few years older than Eleanor and having a stellar season herself having won several city tournaments around BC and ultimately prevailed 7-5, 6-3 coming from behind down 5-3 in the first set.

Later that same afternoon, Eleanor and Deacon then teamed up together and won the Canadian open doubles title. It would be the first of two national doubles titles Eleanor would win during her career. The second, in 1940, came while teamed up with partner Jean Milne, who earlier in the same tournament Eleanor had defeated in the national singles final for her one career Canadian singles title. She also won the mixed doubles national title in 1939.

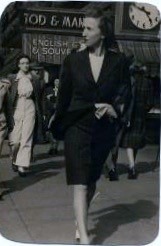

Based on the performances of Eleanor and Deacon at nationals, both were named to a small four-member Canadian team that would travel nearly halfway around the world to the hallowed grass courts of Wimbledon in London the following year in 1935. With the world still gripped tightly by the Great Depression, funds were tight and the BC Lawn Tennis Association had no money to help with Eleanor and Deacon’s travel costs. Luckily, supporters from North Vancouver stepped up and paid their way. Going overseas to Europe was a much bigger trip at that time than it is today and being only 18 added to the allure.

“It really doesn’t seem like it was all that long ago,” Eleanor said in 1993. “It was a marvelous time, a really exciting adventure for a young girl.”

Departing from Vancouver, it took four days for Eleanor and Deacon’s train to arrive in Montreal. After staying overnight there, they then sailed for Britain aboard the liner Alaunia for another four days at sea.

“It…seemed like forever on the boat to Liverpool,” recalled Eleanor.” The train was probably the worst part. There was nothing to see, nothing to do and not much room to move around. The boat was much better. There was a gym and we worked out every day and did our exercises. We’d play shuffleboard and walk around the deck as often as we could.”

In Wimbledon they stayed at a beautiful private home complete with its own grass court, which allowed them both ample practice time. It was easy to be impressed with the scale and glamour of the most prestigious tennis tournament in the world. Thousands, including the rich, movie stars, politicians, even a few royals milled about in the stands watching matches and nibbling on strawberries and cream while sipping champagne.

In Wimbledon they stayed at a beautiful private home complete with its own grass court, which allowed them both ample practice time. It was easy to be impressed with the scale and glamour of the most prestigious tennis tournament in the world. Thousands, including the rich, movie stars, politicians, even a few royals milled about in the stands watching matches and nibbling on strawberries and cream while sipping champagne.

“Wimbledon wasn’t big like it is now but to me, it certainly seemed big enough back then,” recalled Eleanor decades later. “I just wish I had been a little bit older than 18 when I was there, because now that I look back on it, I don’t feel I really appreciated how special it was to be there.”

Eleanor also likely didn’t realize the significance of her appearance from a historical perspective. Along with Deacon, they were the first British Columbian women ever to play at Wimbledon. From a national point of view, the two North Vancouver women were just the fifth and sixth Canadian women to appear at Wimbledon and only the third and fourth to actually play matches there. Preceding them were Toronto’s Violet Summerhayes, who played in 1907; Montreal’s I. Haselden, who played in 1924; Toronto’s Mrs. H.F. Wright, who appeared in 1926, but withdrew before playing; and Toronto’s Olive Wade, who appeared in 1932, but also withdrew before playing due to illness.

Eleanor received first round byes in the singles, doubles, and mixed doubles competitions. In singles, she lost in the second round to Belgium’s Josane de Meulemeester 6-1, 6-4. Eleanor and Deacon teamed up together in doubles, but bowed out in the second round to Belgian sisters Beatrice and Elise Watson 7-5, 6-3. Eleanor also teamed with Montreal’s Robert Murray in mixed doubles but fell to a Czech and British pair in the second round.

The headline makers that year were England’s Fred Perry, who won his second of three straight Wimbledon men’s singles titles, and the American legend Helen Wills Moody who came from behind in the final to win her seventh of eight career Wimbledon women’s singles titles.

The headline makers that year were England’s Fred Perry, who won his second of three straight Wimbledon men’s singles titles, and the American legend Helen Wills Moody who came from behind in the final to win her seventh of eight career Wimbledon women’s singles titles.

Although she failed to advance past the second round, Eleanor’s appearance at Wimbledon was also significant from a fashion perspective. Wimbledon is famous for the all-white dress code required of all competitors which dates back to the Victorian era as an attempt to hide the appearance of unseemly sweat. What players and celebrities are wearing always seems to be part of the conversation at Wimbledon every year right up to the present day. Eleanor inadvertently found herself at the center of that conversation in 1935. Her all-white outfit included shorts, which was not uncommon among women’s tennis players in BC at that time or even other sports like track and field and basketball, but for stuffy Wimbledon, this was unique, almost scandalous. As Mary Ormsby wrote, “wearing shorts that were a little TOO short for the delicate English sensibilities of the time” raised some eyebrows. Despite the fact England’s Eileen Bennett had been the first to wear shorts on Centre Court in 1934, a year later photos of Eleanor playing in shorts appeared in a London newspaper causing a minor sensation. Her uncle, who was in England at that time, was embarrassed enough that he chose not to attend her matches. Eleanor had a hard time understanding what all the fuss was about.

“The English girls wore those divided skirts right down to their knees,” she said. “We wore shorts that weren’t really even all that short but the English thought we were terrible; they were quite scandalized… [chuckling] But the funny thing was that when the English girls were in Canada or the States playing, the first thing they did was put on a pair of shorts because they were far more comfortable.”

It wasn’t long after that shorts became common wear for all women playing at Wimbledon and Eleanor, as one of the first to don them, helped bring that change about.

After Wimbledon wrapped up, the Canadian quartet went to play at another tournament in Scotland before making the long trip back home. Although Eleanor’s career was just getting started at the elite level with most of her highlight accomplishments still to come, this early trip to Wimbledon proved to be her one and only appearance there. Her later play certainly warranted a return trip, but for one reason or another, it never came to pass.

“I felt that there was always pressure for me to stay in Canada because there was a big western tournament going on around that time in Vancouver,” she explained years later. “Tennis officials always wanted me to stay behind because I was the only Canadian at the time who could beat the American girls. And that was fine with me because I enjoyed any kind of competition, really, and I did a fair amount of travelling in Canada and the United States.”

Beyond the national titles Eleanor won mentioned earlier, she was also the national runner-up in women’s doubles in 1936, in mixed doubles in 1936 and 1940, and in women’s singles in 1947 losing in the final to American Graclyn Wheeler Kelleher. In fact, she was the only Canadian to make any final that year at nationals.

Beyond the national titles Eleanor won mentioned earlier, she was also the national runner-up in women’s doubles in 1936, in mixed doubles in 1936 and 1940, and in women’s singles in 1947 losing in the final to American Graclyn Wheeler Kelleher. In fact, she was the only Canadian to make any final that year at nationals.

Eleanor was also ranked as the number one singles player in Canada five different times in 1937, 1939, 1940, 1946, and 1948, a feat not matched for forty years until Carling Bassett emerged. Eleanor was also ranked second nationally in 1934 and 1938 and third in 1936. In 1940, she finished as the runner-up for the Bobbie Rosenfeld Award as Canada’s female athlete of the year behind Dorothy Walton of badminton fame. Certainly, these lists for Eleanor would be longer if not for the outbreak of World War II which halted most tennis tournaments and rankings from 1941-45. That disruption unfortunately coincided with the prime of her career. None the less, by 1941, she was described as ‘the queen of Canadian tennis courts’ and possibly the best women’s player ever developed in Canada. Many felt she was the only Canadian player of that era who could compete against the top American singles players.

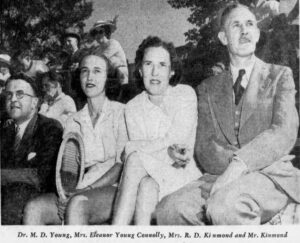

Nothing confirms that better than one of Eleanor’s most overlooked accomplishments today in winning the Western Canadian Lawn Tennis Championships three straight times in 1940, 1941, and 1946 (no tournaments were held from 1942-45). Staged on the grass courts of the Vancouver Lawn Tennis and Badminton Club, her home club, at the time this tournament was considered harder to win than the Canadian nationals because it attracted top players from Washington, Oregon, and California, plus other US states. No other Canadian player ever achieved greater success in this tournament, which ran until 1974 before it was discontinued. Even more than Wimbledon or her Canadian titles, Eleanor considered her record at the Western Canadians her proudest accomplishment.

“A lot of Americans came up for that and everyone expected an American to win, so that was my biggest tournament,” she told The Province in 1993.

During the war, Eleanor married Hugh Connolly of Duncan, but they divorced just a few years later. After she retired from competitive tennis in 1948, she married Joe Stonehouse and they had five children together.

Modest to a fault, remarkably Eleanor rarely ever spoke about her own tennis career even to her own children. It wasn’t until she passed away many years later in 1995 at the age of 79 that her children discovered many of her trophies tucked away all over the house.

“She never talked about her tennis,” said son Jim. “She never taught us how to play tennis. She just had five kids and it was a lot of work. It wasn’t until I was in my middle teens that I even found out she played tennis. But we didn’t know to what degree. It’s partly my fault, because if you don’t know you don’t ask. If I’d have known more, I probably would have asked her more questions.”

“She never talked about her tennis,” said son Jim. “She never taught us how to play tennis. She just had five kids and it was a lot of work. It wasn’t until I was in my middle teens that I even found out she played tennis. But we didn’t know to what degree. It’s partly my fault, because if you don’t know you don’t ask. If I’d have known more, I probably would have asked her more questions.”

Jim remembers his mother’s strong independent spirit and that she was often happiest outdoors at the beach or in her younger days riding horses or going hunting and fishing. She was also a loving mom, who gave everything for her kids particularly during tough times. At one point her husband lost his trucking business and struggled to find work after that. As she had on the tennis court, Eleanor faced every challenge and never stopped battling.

“I think what she took into tennis, she took into motherhood, she treated us great,” remembered Jim. “She was a great mother. She did everything she possibly could to make our lives better, which wasn’t always easy because we didn’t have a lot of money. She just never complained. Never said we don’t have this or that. She’d feed us before she fed herself. Unselfish. So we tried to take care of her later on.”

Although he never saw his mom in action, based on how she was as his mother Jim speculated on how she played as one of Canada’s top tennis players.

“I think she probably played more with heart than with talent,” he said. “She had talent obviously, but I think she wanted to win more than anything and that just drove her. Just like if she wanted to learn how to fish or how to shoot a gun and go hunting and doing all those things.”

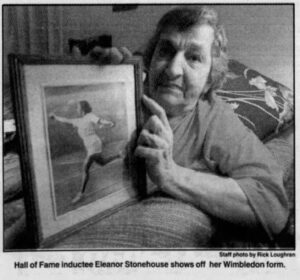

It was only in the final years of Eleanor’s life that her family began to realize how significant an athlete she had been in her younger years. She had been one of the inaugural athletes inducted into the North Shore Sports Hall of Fame in North Vancouver in 1968, but it wasn’t until 1993 that it really hit home, when she was inducted into the Canadian Tennis Hall of Fame, the same year as fellow BC Sports Hall of Fame inductees Robert Powell and Marjorie Leeming. Battling emphysema that later took her life, Eleanor was unable to travel to the induction in Toronto, but was interviewed live via satellite feed by Tom Mayenknecht, then Tennis Canada’s director of communications and now of course chair of the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

“It just seems like a dream to me,” Eleanor told the large dinner crowd. “And it’s so long ago I can’t believe it. It’s a wonderful thing for me now at my age.”

She told the Toronto Star’s Mary Ormsby that “it’s been over 50 years since I played and sometimes, it seems so long ago that it feels like it didn’t even happen. But it was a marvelous surprise for me and I’m very proud I’m in the Hall of Fame.”

She told the Toronto Star’s Mary Ormsby that “it’s been over 50 years since I played and sometimes, it seems so long ago that it feels like it didn’t even happen. But it was a marvelous surprise for me and I’m very proud I’m in the Hall of Fame.”

The Province also interviewed Eleanor prior to her induction, asking her what she felt was the biggest difference in tennis from when she played. It was the amount of money in the sport, she said.

“We never got any money then, just trophies,” she recalled. “I think this money business is ridiculous. There’s just too much money, not just in tennis but in all sports.”

Although she didn’t talk about much about her own career, she continued to avidly follow tennis right until her final days.

“It was always on the TV,” remembered Jim. “If there was a match on, she was in front of the TV.”

Eleanor liked many of the biggest stars of the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s like Björn Borg, Jimmy Connors, and Martina Navratilova, but she loved following the rare Canadians who reached the highest levels of play like Carling Bassett and especially fellow BC Sports Hall of Famers Helen Kelesi and Grant Connell.

“Anybody Canadian, she’d be behind them 100%,” Jim confirmed.

With that in mind, somewhere Eleanor must be just beaming watching the heights Canadian tennis has reached recently. Top-ranked Canadian players like Bianca Andreescu and Leylah Fernandez on the women’s side and Felix Auger Aliassime and Denis Shapovalov on the men’s are challenging for and occasionally winning top tournaments every year. Combine that with Canada’s recent Davis Cup victory late last year after years of record-breaking success in that competition and there has never been a better era for the sport in Canada. If she isn’t already there, Eleanor would be in heaven seeing all this.

In another era, with more opportunities available to her, she may well have reached the heights of some of these well-known Canadian players who followed the pioneering trail she blazed through the tennis world.

In another era, with more opportunities available to her, she may well have reached the heights of some of these well-known Canadian players who followed the pioneering trail she blazed through the tennis world.

After she passed away, it was son Jim who championed his mother’s cause and nominated her to the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Upon learning his mother would be inducted, he was thrilled to know his mother would join many of BC’s greatest tennis players and builders in the Hall.

“Very proud of her, so I’m very happy that she’s in there,” he said. “I think she deserves it and I’m pretty sure if it was just her and she was here, she wouldn’t have even asked to be in. Just because she didn’t think it’s that big of a deal and she didn’t like to brag. But I felt she does deserve it and that’s why I pushed. I’m glad it all happened.”

As part of the Class of 2023, Eleanor (Young) Stonehouse was formally inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Pioneer category at the annual Induction Gala held June 1, 2023 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.